Peregrine

| Irish Name: | Fabhcún gorm |

| Scientific name: | Falco peregrinus |

| Bird Family: | Raptors |

green

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

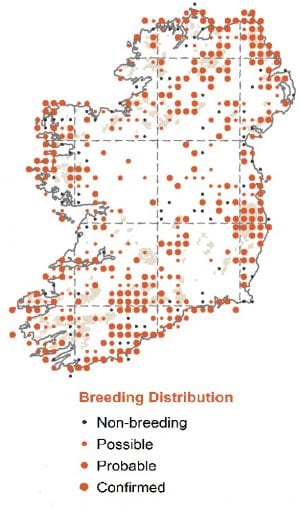

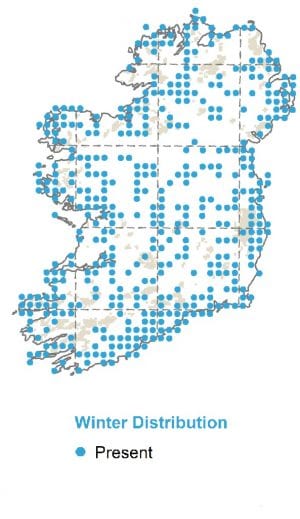

Widespread resident in Ireland.

Identification

A bird of prey (raptor) with a short hooked bill. A species of falcon with a heavy powerfully built body, medium length tail and wings which are broad close to the body and pointed at the tip. Sexual size difference, the female is larger than the male. Male and female plumages are the same, unlike Merlins, the species most likely to be confused with Peregrine Falcon. Adults are bluey grey above, with a barred tail; the underparts are white and finely barred, the check, throat and upper breast are plain white and contrast with a black hood and thick moustachal stripe. Juvenile birds are similar to adults but have brownish upperparts and streaked, not barred, feathers on the body.

Voice

Mainly silent away from its breeding site. Main call is a hard persistent cackling.

Diet

Mainly birds, usually taken in the air and sometimes on the ground or on water. Employs spectacular hunting technique where the bird 'stoops' from high above its intended prey, with its wings held close into the body, reaching great speeds. Estimates of speeds vary, but it seems likely that birds reach speeds in excess of 300km/hour, making it the fastest animal on the planet. Kills its prey with force of its impact using its legs at the last moment to inflict the killer blow. Prey includes pigeons, including feral birds, thrushes, waders and wildfowl, gulls and seabirds.

Breeding

Breeds on coastal and inland cliffs. Most birds on the coast breed on the south, west and north coasts, coastal breeding on the east coast is limited by the availability of suitable nesting cliffs. Most inland birds breed on mountain cliffs but will also breed at lower levels. The species is still recovering from a dramatic and well documented decline in the 1950s and 60s due to the effects of pesticide poisoning. The responsible pesticides have been banned and the species has been recovering slowly.

Wintering

Resident in Ireland, but shows some movement away from its breeding areas in the winter. Can be found on the coast, especially on estuaries where they hunt on concentrations of water birds. Some birds move into cites, where feral pigeons provide suitable prey; individuals have been captured on film by a road traffic camera looking down over the quays in central Dublin. Some birds at this time of the year could have immigrated from Britain or even further afield.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

Wildlife in Buildings documentary

[vc_row type="in_container" full_screen_row_position="middle" scene_position="center" text_color="dark" text_align="left" overlay_strength="0.3" shape_divider_position="bottom" shape_type=""][vc_column column_padding="no-extra-padding" column_padding_position="all" background_color_opacity="1" background_hover_color_opacity="1" column_link_target="_self" column_shadow="none" column_border_radius="none" width="1/1" tablet_width_inherit="default" tablet_text_alignment="default" phone_text_alignment="default" column_border_width="none" column_border_style="solid"][vc_column_text]

Certain species are expected residents within our buildings, and for some the association with buildings is apparent even from their names, such as the ‘House Martin’ which builds its mud nest in the apex of the roof of occupied houses, and the ‘Barn Swallow’ which travels from Africa to nest in farmyards throughout the country. The vision of a Barn Owl floating silently from a ruined castle at dusk may seem familiar, but less expected occupants may be a pair of Kestrels nesting in a flower box outside a busy kitchen window, or a female Pine Marten raising her kits in the roof space of an occupied dwelling. Of course, much of the wildlife which use buildings go unnoticed, such as bats roosting in the attic of a house in which the inhabitants beneath remain blissfully unaware of their presence.

Given the importance of buildings for wildlife, changes to the built environment can affect wildlife associated with it. Wildlife in buildings can often be harmed during works due to a lack of awareness of their presence or indeed knowledge of how plan renovations and works in order to avoid disturbance, which is usually always possible. The loss of old stone structures due to demolition, dilapidation or renovation is linked to declines in species such as Barn Owl and Swift, which are dependent on these structures. Modern buildings do not provide the same opportunities for wildlife. However, there is a lot that we can do to improve modern buildings for wildlife to ensure that we continue to make space for nature.

BirdWatch Ireland and CrowCrag Productions in partnership with Laois County Council, Clare County Council and Tipperary County Council and supported by the National Biodiversity Action Plan Fund of the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage have produced a nature documentary to celebrate the wildlife which have taken up residence in the built environment, and to showcase some of our most iconic wildlife species which are reliant on buildings for their survival.

John Lusby, BirdWatch Ireland, commented, ‘We wanted to celebrate the importance of buildings for wildlife and to create a better link between our built heritage and our natural heritage – as the two are intertwined. The diversity of species which use buildings, and the ways in which they have adapted to use the built environment, is truly astonishing. As the built environment is constantly changing, we need to make sure that we avoid disturbance to sensitive species and also to continue to provide space for wildlife in buildings, which has benefits for wildlife as well as ourselves. We hope that this feature increases awareness and appreciation of the importance of the built environment for wildlife and provides the necessary information to help conserve some of our most vulnerable and iconic wildlife which are dependent on buildings for their survival’.

Roisin O’Grady, Heritage Officer with Tipperary County Council said ‘We share the world with nature and it can be closer to us than we think. Tipperary County Council is delighted to support this film highlighting the importance of our built environment, heritage or otherwise in providing shelter for such a variety of species, some of which are our most vulnerable. Given the high levels of habitat loss we have experienced over the last number of years it is more important than ever to be aware of how species have adapted to our built environment and how we can support this ‘co-habitation’ and equally important in newer development how we ‘make space’ for nature’.

Congella McGuire, Heritage Officer with Clare County Council commented ‘The Local Authority Heritage Officer Network is delighted to be associated with this Wildlife in Buildings video and the guidance booklet ‘Wildlife in Buildings: linking our built and natural heritage’ both of which were produced with the support of the Local Authorities and National Biodiversity Action Plan Fund’.

The video ‘Wildlife in Buildings: linking our built and natural heritage’ is available to view below or here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lQt3C8uI5E This video accompanies the guidance booklet on Wildlife in Buildings, which is available here: https://www.kerrycoco.ie/wildlife-in-buildings/

‘Wildlife in Buildings: linking our built and natural heritage’ was produced by BirdWatch Ireland, Kerry County Council and Donegal County Council, with funding from the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage through the National Biodiversity Action Plan Fund.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lQt3C8uI5E&t=782s[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

A new video highlights the importance of the built environment for wildlife and celebrates the species which have adapted to live alongside us and share our homes, and the measures that we can take to ensure we make space for nature

People live in buildings, and wildlife lives in “nature” - right? Well, not quite. For as long as we have built structures for our protection and shelter, wildlife has taken advantage of these buildings for the very same reasons. From the diverse range of birds and mammals which have colonised abandoned ruins in remote rural landscapes, to wildlife which has moved into suburban and urban areas to live alongside us and even share our homes, buildings have become an integral component of the Irish landscape for biodiversity. A ruined Abbey which is used by a wide range of wildlife © John Lusby

A ruined Abbey which is used by a wide range of wildlife © John Lusby

Certain species are expected residents within our buildings, and for some the association with buildings is apparent even from their names, such as the ‘House Martin’ which builds its mud nest in the apex of the roof of occupied houses, and the ‘Barn Swallow’ which travels from Africa to nest in farmyards throughout the country. The vision of a Barn Owl floating silently from a ruined castle at dusk may seem familiar, but less expected occupants may be a pair of Kestrels nesting in a flower box outside a busy kitchen window, or a female Pine Marten raising her kits in the roof space of an occupied dwelling. Of course, much of the wildlife which use buildings go unnoticed, such as bats roosting in the attic of a house in which the inhabitants beneath remain blissfully unaware of their presence.

Swift © Artur Tabor, Lesser Horseshoe Bat © Ruth Hanniffy

Swift © Artur Tabor, Lesser Horseshoe Bat © Ruth Hanniffy

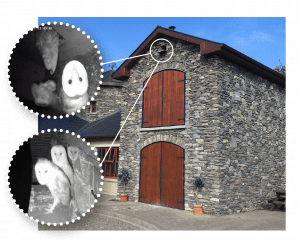

Given the importance of buildings for wildlife, changes to the built environment can affect wildlife associated with it. Wildlife in buildings can often be harmed during works due to a lack of awareness of their presence or indeed knowledge of how plan renovations and works in order to avoid disturbance, which is usually always possible. The loss of old stone structures due to demolition, dilapidation or renovation is linked to declines in species such as Barn Owl and Swift, which are dependent on these structures. Modern buildings do not provide the same opportunities for wildlife. However, there is a lot that we can do to improve modern buildings for wildlife to ensure that we continue to make space for nature.

There are many ways we can improve modern buildings for wildlife such as this example, where a purpose built Barn Owl nest site was incorporated in the building

There are many ways we can improve modern buildings for wildlife such as this example, where a purpose built Barn Owl nest site was incorporated in the building

BirdWatch Ireland and CrowCrag Productions in partnership with Laois County Council, Clare County Council and Tipperary County Council and supported by the National Biodiversity Action Plan Fund of the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage have produced a nature documentary to celebrate the wildlife which have taken up residence in the built environment, and to showcase some of our most iconic wildlife species which are reliant on buildings for their survival.

John Lusby, BirdWatch Ireland, commented, ‘We wanted to celebrate the importance of buildings for wildlife and to create a better link between our built heritage and our natural heritage – as the two are intertwined. The diversity of species which use buildings, and the ways in which they have adapted to use the built environment, is truly astonishing. As the built environment is constantly changing, we need to make sure that we avoid disturbance to sensitive species and also to continue to provide space for wildlife in buildings, which has benefits for wildlife as well as ourselves. We hope that this feature increases awareness and appreciation of the importance of the built environment for wildlife and provides the necessary information to help conserve some of our most vulnerable and iconic wildlife which are dependent on buildings for their survival’.

Kestrel in flight © Michael O'Clery, Kestrel nest in castle © John Lusby

Kestrel in flight © Michael O'Clery, Kestrel nest in castle © John Lusby

Roisin O’Grady, Heritage Officer with Tipperary County Council said ‘We share the world with nature and it can be closer to us than we think. Tipperary County Council is delighted to support this film highlighting the importance of our built environment, heritage or otherwise in providing shelter for such a variety of species, some of which are our most vulnerable. Given the high levels of habitat loss we have experienced over the last number of years it is more important than ever to be aware of how species have adapted to our built environment and how we can support this ‘co-habitation’ and equally important in newer development how we ‘make space’ for nature’.

Renovations and other works on buildings can have unintended consequences for wildlife if not planned appropriately © Conor Kelleher

Renovations and other works on buildings can have unintended consequences for wildlife if not planned appropriately © Conor Kelleher

Congella McGuire, Heritage Officer with Clare County Council commented ‘The Local Authority Heritage Officer Network is delighted to be associated with this Wildlife in Buildings video and the guidance booklet ‘Wildlife in Buildings: linking our built and natural heritage’ both of which were produced with the support of the Local Authorities and National Biodiversity Action Plan Fund’.

Workhouse in ruins © Michael O'Clery, Barn Owls in chimney nest © John Lusby

Workhouse in ruins © Michael O'Clery, Barn Owls in chimney nest © John Lusby

The video ‘Wildlife in Buildings: linking our built and natural heritage’ is available to view below or here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lQt3C8uI5E This video accompanies the guidance booklet on Wildlife in Buildings, which is available here: https://www.kerrycoco.ie/wildlife-in-buildings/

‘Wildlife in Buildings: linking our built and natural heritage’ was produced by BirdWatch Ireland, Kerry County Council and Donegal County Council, with funding from the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage through the National Biodiversity Action Plan Fund.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5lQt3C8uI5E&t=782s[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

BirdWatch Ireland urge people to report any signs of bird flu in their area

A number of cases of Avian Influenza (‘bird flu’) have been confirmed in wild birds in Ireland since the start of the month. There are no known risks to human health, and similarly this isn’t going to affect your garden birds, but please watch out for sick or dead waterbirds, birds of prey, or potentially large numbers of dead crows or starlings which may have died as a result of this virus. If you find any such birds, don’t touch them, but rather report them immediately to the Department of Agriculture via the link below. It is important that any potential cases of avian influenza are investigated and documented appropriately in order to monitor the spread of the virus.

Report any dead or sick waterbirds or birds of prey here.

There are numerous strains and subtypes of the avian influenza virus that each vary in severity. The strain that has recently been detected in some wild birds in Ireland is Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) H5N1, which spreads easily between birds and causes illness, with a high death rate. This strain had been detected in a number of European countries before arriving into Ireland this month as wild birds migrate southwards and westwards for the winter. BirdWatch Ireland are part of an early warning system with regard to surveillance for signs of disease in wild birds, together with colleagues in the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine and the National Association of Regional Game Councils (NAGC). What is the current situation with regards Avian Influenza in the Republic of Ireland? To date there have been confirmed mortalities from the H5N1 strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza in counties Galway, Roscommon, Offaly, Donegal and Kerry, with further cases under investigation in other counties. The birds known to have been infected so far are Whooper Swans, Greylag Geese, Peregrine Falcons and a White-tailed Eagle. In winter, waterbirds of a range of different species congregate together at wetlands across the country, which allows the virus to spread easily amongst waterbird flocks and between species. When these birds become sick, they are easy prey for raptors such as Peregrines and Eagles, hence these species are often infected also. What are the signs to watch out for? Firstly, it’s important to be aware that the only wild birds expected to become infected at present are waterbird species (wildfowl, waders, gulls) and birds of prey. If you own chickens or other poultry then please consult the Department of Agriculture website for further advice. If you find a dead waterbird of bird of prey, where the cause of death isn’t obvious (e.g. car collision) then it’s best to report it to the Department of Agriculture, so it can be collected and tested. If you find a bird of these species that’s acting unwell or otherwise behaving strangely, then this too should be reported. It’s important to note that potentially sick birds should not be brought to a wildlife rehabilitator or the National Wildlife Hospital in Meath, as this could risk infecting the birds already in their care. If you find a sick bird, report it via this link first, and secondly you may want to call the Avian Influenza Hotline (01 6072512 during office hours or 01 4928026 outside office hours). Should I stop feeding my garden birds? Although it is possible for garden bird species to get bird flu, they are at very low risk at present, for the simple reason that they don’t interact with the species currently infected (i.e. waterbirds). As such, there is no reason to stop feeding your garden birds. If the situation deteriorates and this advice changes, we will spread the word and ensure everyone knows. What should I do if I own poultry? To date there have been no cases in poultry flocks in Ireland, but poultry owners should familiarise themselves with Department of Agriculture guidance on biosecurity and the new regulations introduced as a precautionary measure. It should be stressed that there is no food safety risk for consumers and that properly cooked poultry and poultry products are safe to eat. What is the situation in Northern Ireland? Full details on restrictions for poultry flock owners, and where to report possible cases in wild birds in Northern Ireland, can be found on the DAERA website here. Further information and updates are regularly made available on the Department of Agriculture website:https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/50ce4-avian-influenza-bird-flu/

A ruined Abbey which is used by a wide range of wildlife © John Lusby

A ruined Abbey which is used by a wide range of wildlife © John Lusby Swift © Artur Tabor, Lesser Horseshoe Bat © Ruth Hanniffy

Swift © Artur Tabor, Lesser Horseshoe Bat © Ruth Hanniffy There are many ways we can improve modern buildings for wildlife such as this example, where a purpose built Barn Owl nest site was incorporated in the building

There are many ways we can improve modern buildings for wildlife such as this example, where a purpose built Barn Owl nest site was incorporated in the building  Kestrel in flight © Michael O'Clery, Kestrel nest in castle © John Lusby

Kestrel in flight © Michael O'Clery, Kestrel nest in castle © John Lusby Renovations and other works on buildings can have unintended consequences for wildlife if not planned appropriately © Conor Kelleher

Renovations and other works on buildings can have unintended consequences for wildlife if not planned appropriately © Conor Kelleher Workhouse in ruins © Michael O'Clery, Barn Owls in chimney nest © John Lusby

Workhouse in ruins © Michael O'Clery, Barn Owls in chimney nest © John Lusby