As we creep our way into winter, as the days get shorter, the nights longer and everything colder, you could be forgiven for despairing about the coming and going of seasons and why can’t the summer just be that little bit longer??? But there is some good news!! Yes, although we are entering the throes of winter, it is not all doom and gloom as we are seeing the return of Ireland’s overwintering waterbirds.

Every year Ireland supports an incredible array of waterbird species, making use of our relatively mild climate to fatten up before returning to their breeding grounds. Ireland, where a full frozen lake is a rarity, offers these birds a fantastic opportunity for feeding during the winter months.

Here on the Dublin Bay Birds Project, our recent monthly surveys, have shown a steady increase in the number of waterbirds. Dublin Bay, and Ireland as a whole, play host to a great many fascinating and charismatic waterbirds each winter. The Brent Goose returning from its Canadian high Arctic breeding grounds is always an indication of the changing of the seasons. They are a common sight in Irish coastal counties, as they deplete the food supplies in the estuaries and begin to feed away from the coast on grassland areas, the sight of them flying overhead becomes more common.

However, I wanted to talk a little more about another winter migrant, the Bar-tailed Godwit.

(Photo: Dick Coombes – A large mixed flock of Bar-tailed Godwit and Knot, a familiar sight during the winter months.)

Bar-tailed Godwit

The Bar-tailed Godwit is a species that I particularly enjoy seeing return. And although a small number do spend their summers in Ireland, they are rather scarce, with the vast majority of our over wintering population returning from September onwards.

One reason that I look forward to seeing the return of Bar-tailed Godwits is that many individuals will still have vestiges of their summer finery in early autumn. These elegantly proportioned birds will often return to our coasts with a ruff red breast that contrasts with their beautifully scalloped back and wings. Though the scalloping remains in the winter (and is one of the most useful ways to distinguish this bird from its closely related Black-tailed Godwit), the overall impression is more dull and grey as they lose their red summer plumage. Autumn is a great time to see a Bar-tailed Godwit in its summer plumage.

(Photo: Richard T Mills – Bar-tailed Godwit in non-breeding plumage.)

These birds are most often encountered probing for polychaete worms on sandy substrates. As this is the Dublin Bay Birds Project, this blog entry is somewhat Dublin centric (apologies!), and I can say that if you want to see a Bar-tailed Godwit around the capital you are best served to head out to the sandy areas around Bull Island and the Tolka estuary, you could also encounter these anywhere from Sandymount Strand down to Seapoint on a low tide when much of the sand is exposed by the tide, but if you are on the south and west coasts you can see them at several sites including Wexford Harbour and Slobs (Wexford), Dungarvan Harbour (Waterford), Ballymacoda (Cork), Shannon & Fergus estuary (Clare/Limerick), Tralee Bay (Kerry), The Mullet, Broadhaven and Blacksod Bays (Mayo), Inner Galway Bay (Galway) and Ballysadre Bay (Sligo), to name just a few. You can also go on to BirdTrack to see if Bar-tailed Godwits have been spotted anywhere near you recently.

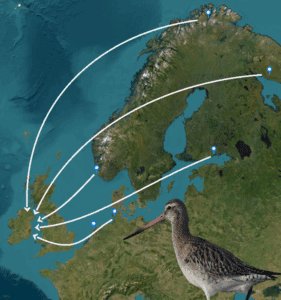

The Dublin Bay Birds project has fitted 100 Bar-tailed Godwits with uniquely coded colour-rings which are safely fitted to the birds’ legs under a special license. The subsequent observations that we get from people about where they’ve seen these birds help us to better understand the areas they use in Dublin but also the location of their breeding origin and staging sites used when migrating to and from their summer breeding grounds. This work highlighted the use of South Norway, Finland, The Wadden Sea and The Netherlands as key staging sites, whilst showing the breeding grounds of Northern Norway and the Tromsky District, Russia (see map below). You can read more about that work here.

(Breeding grounds and stopover sites of colour tagged Bar-tailed Godwits from the Dublin Bay Birds Project.)

The Bar-tailed Godwits that come to Ireland for the winter have a breeding range across Northern Europe over to Western Siberia. But Conklin et al. (2025), through genetic bar-coding, showed that there are more birds that breed in the Taymyr Peninsula, Northern Russia that visit Europe than previously thought. Most of the birds from this ‘sub-species’ of Bar-tailed Godwit overwinter in Africa but this new paper suggested that a significant proportion of these also overwinter in Europe.

It is not clear if this change in wintering strategy, or range expansion, is relatively recent, though it was hinted at in a study by a 2008 study (Engelmoer, 2008).

Why different subspecies matter

Understanding sub-species can be important because population trends are calculated at this level. Across the globe six sub-species of Bar-tailed Godwit have now been identified. They may all look similar but they breed in different regions and have different migration strategies. For example, there is one sub-species that migrates from Alaska to New Zealand, and they would encounter different pressures and threats on their ‘flyway’ than the Bar-tailed Godwits that migrate between Siberia and Ireland. Assessing their population sizes and trends separately helps us to understand how the different populations are faring along the different flyways. This, in turn, allows us to target conservation actions where they are most needed to remedy population declines.

Bar-tailed Godwit numbers in Ireland have remained relatively stable across the last 50 years, however now we do not know if this is from one population, lapponica, remaining stable, or from this population declining but being supplemented by additional birds from the taymyrensis population. And this is impossible to assess without the help of DNA bar–coding and analysis. They’re probably not in Ireland, but we can’t know for sure until some DNA analysis is done. Scientific research like this can be a fascinating insight into the migration patterns of waders and how they are adapting in the face of pressures like climate change. Furthermore, the findings from Conklin et al. (2025) highlight that the overall lapponica population (the population that includes Irish wintering birds) is actually tens of thousands birds smaller than we thought. Which has a knock-on effect for how to assess the population here in Ireland. Showing the value of ongoing research and ringing efforts – we can’t assume that populations, behaviour or our assumptions will always remain the same.

(Photo: Mark Carmody – Colour ringed Bar-tailed Godwit from the Dublin Bay Birds Project.)

So, as winter draws in and more birds flock to these shores, the Bar-tailed Godwit is definitely one to look out for, and who knows, you could be spotting a bird that has come to Ireland for the first time ever.

And if you do encounter any Bar-tailed Godwits this year and manage to get any good photos, please do send them in to rgadd@birdwatchireland.ie, we are always delighted to receive any good pictures that you might have and they may possibly be featured in some of our future publications.

With special thanks to Dublin Port company for their continued support and funding for the Dublin Bay Birds Project.