The Dublin City Raptor Survey is back for its second year!

A massive thank you to everyone who has submitted records of raptors so far, we have received 165 records to date! This data will be available on the National Biodiversity Data Centre website. Your records are literally putting raptors on the map and giving us all a better understanding of the distribution of these charismatic species. Please keep these records coming in, logging your sightings here.

Male Sparrowhawk (Shay Connolly).

Male Sparrowhawk (Shay Connolly).

Last year we published an id guide to six species of raptor you’re most likely to encounter in an urban/suburban setting. To aid you in your survey efforts this year, the id guide has been reproduced below.

Your records will greatly help the Dublin City Raptor Survey, a project undertaken by BirdWatch Ireland and Dublin City Council as part of the Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan, with the online data portal provided by the National Biodiversity Data Centre.

Now – onto the id guide.

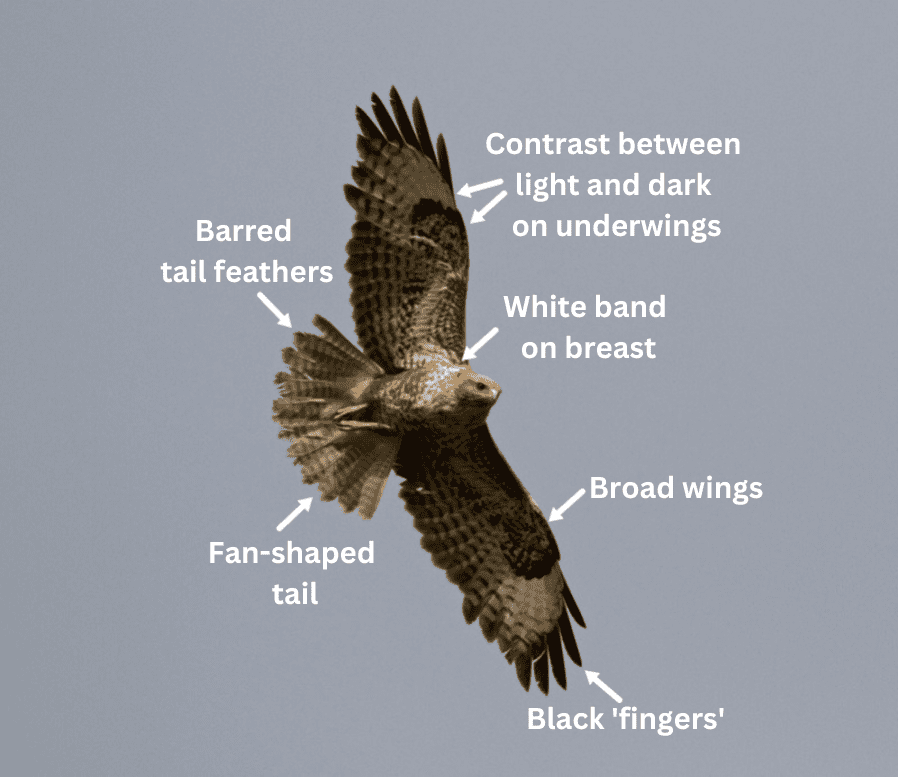

Common Buzzard

Common Buzzard in flight. (Shay Connolly).

Common Buzzard in flight. (Shay Connolly).

Common Buzzard. (Neil O’Reilly).

Common Buzzard. (Neil O’Reilly).

A medium sized bird of prey, the Buzzard ranges from light to dark brown. It is often found perched or soaring beside large roads, searching for roadkill. However, the Buzzard is not just a scavenger and will take small live prey. It will even hunt for earthworms in farmland and parks. The Buzzard is a ‘diurnal hunter’ meaning that it hunts during daylight hours. Its soaring flight is distinctive.

Now, perhaps the most visible bird of prey in Irish skies, it went extinct in Ireland in the late 19th/ early 20th century due to intensive persecution. It arrived back in Co. Antrim in 1933 under its own steam, with the current population most likely arriving from the UK. The Common Buzzard population really took off in the 1990s and it is now a wide-spread species in Ireland.

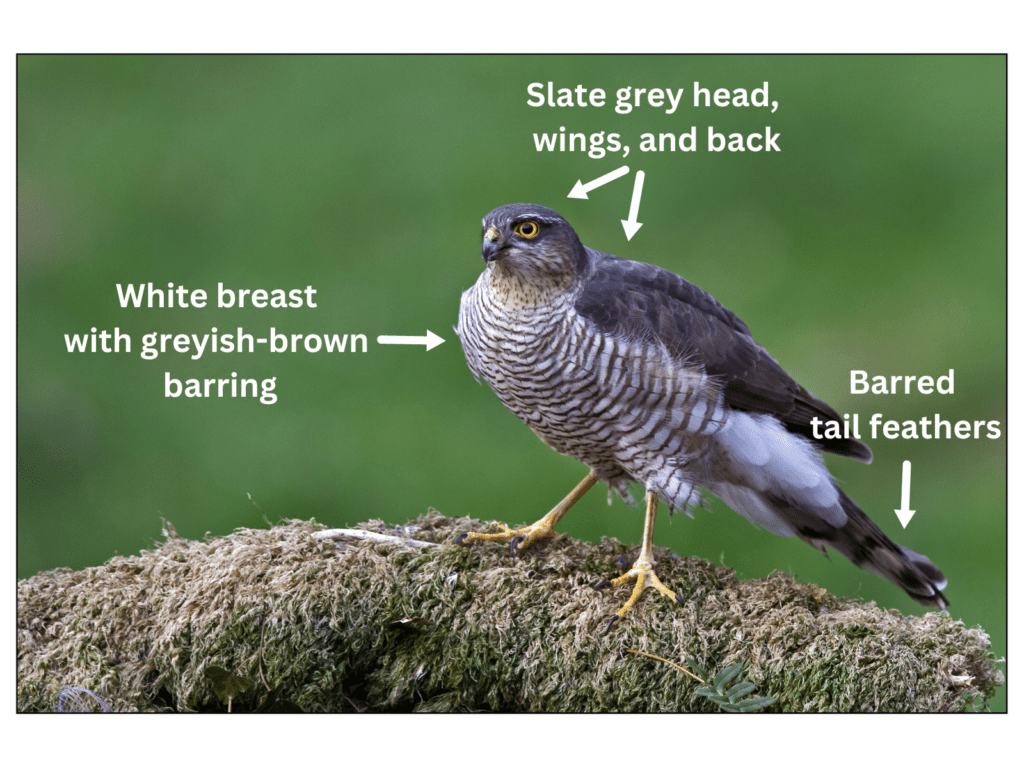

Eurasian Sparrowhawk

Male Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Doyle – main photo; Kurt Kullman – inset photo).

Male Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Doyle – main photo; Kurt Kullman – inset photo).

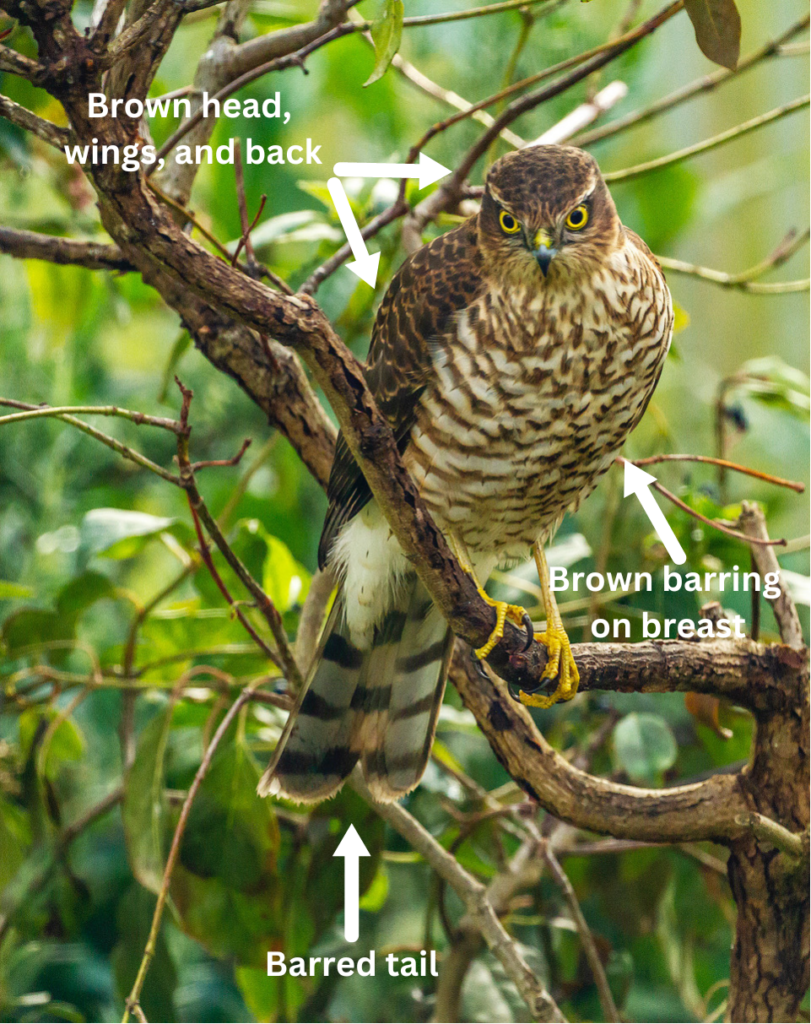

Female Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Ormond).

Female Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Ormond).

Juvenile Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Doyle).

Juvenile Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Doyle).

Sparrowhawks are a relatively small raptor. As is common in raptors, the female Sparrowhawk is larger than the male. Sparrowhawks hunt small birds on the wing, using ambush attacks and their incredible speed and agility to catch their prey, typically low to the ground among trees, hedges and buildings. It has even been recorded hunting small birds, on foot, through hedgerows. It breeds in forests and near urban areas, and can be found nesting and hunting in parklands and gardens.

Peregrine

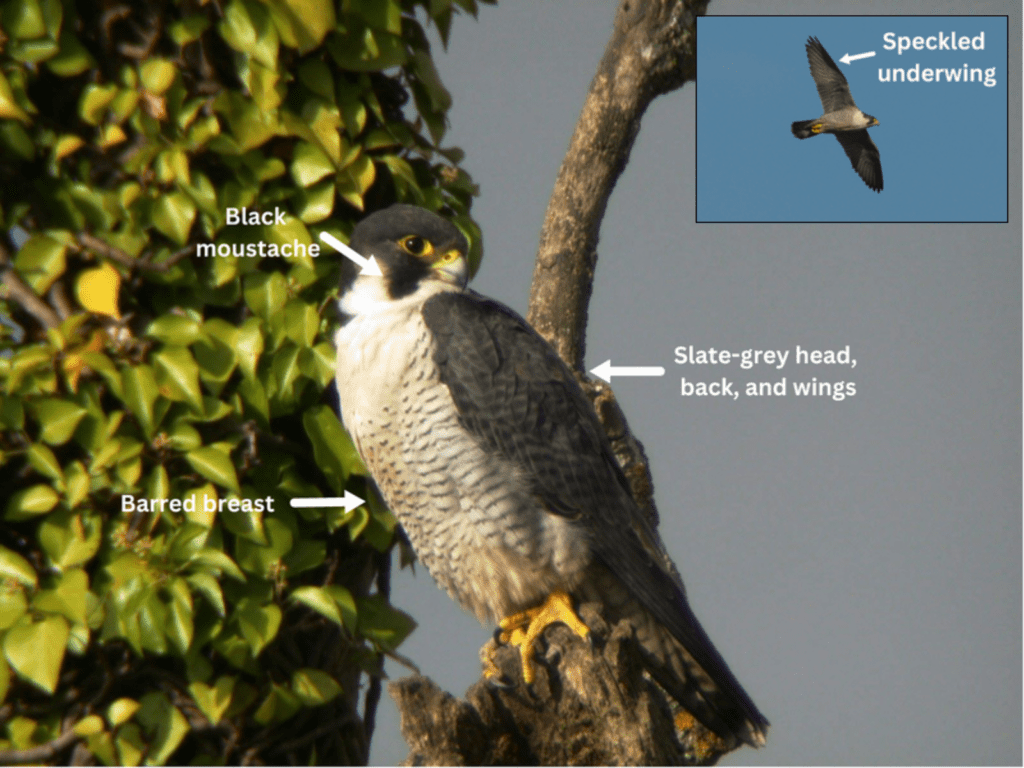

Peregrine. (Shay Connolly – main photo; Colum Clarke – inset photo).

Peregrine. (Shay Connolly – main photo; Colum Clarke – inset photo).

A medium to large bird of prey, the female is larger than the male. It hunts birds on the wing, making spectacular aerial dives to catch its prey. With a diving speed of >300km/ hour it is the fastest animal on earth when diving for prey.

Juvenile Peregrines have streaked rather than barred breasts (i.e. the lines run vertically rather than horizontally on the breast) and they’re browner overall than the adults. Peregrines nest on cliff edges and buildings.

The Irish population took a nosedive in the 1950s and 1960s due to pesticide poisoning, but numbers are currently recovering.

Common Kestrel

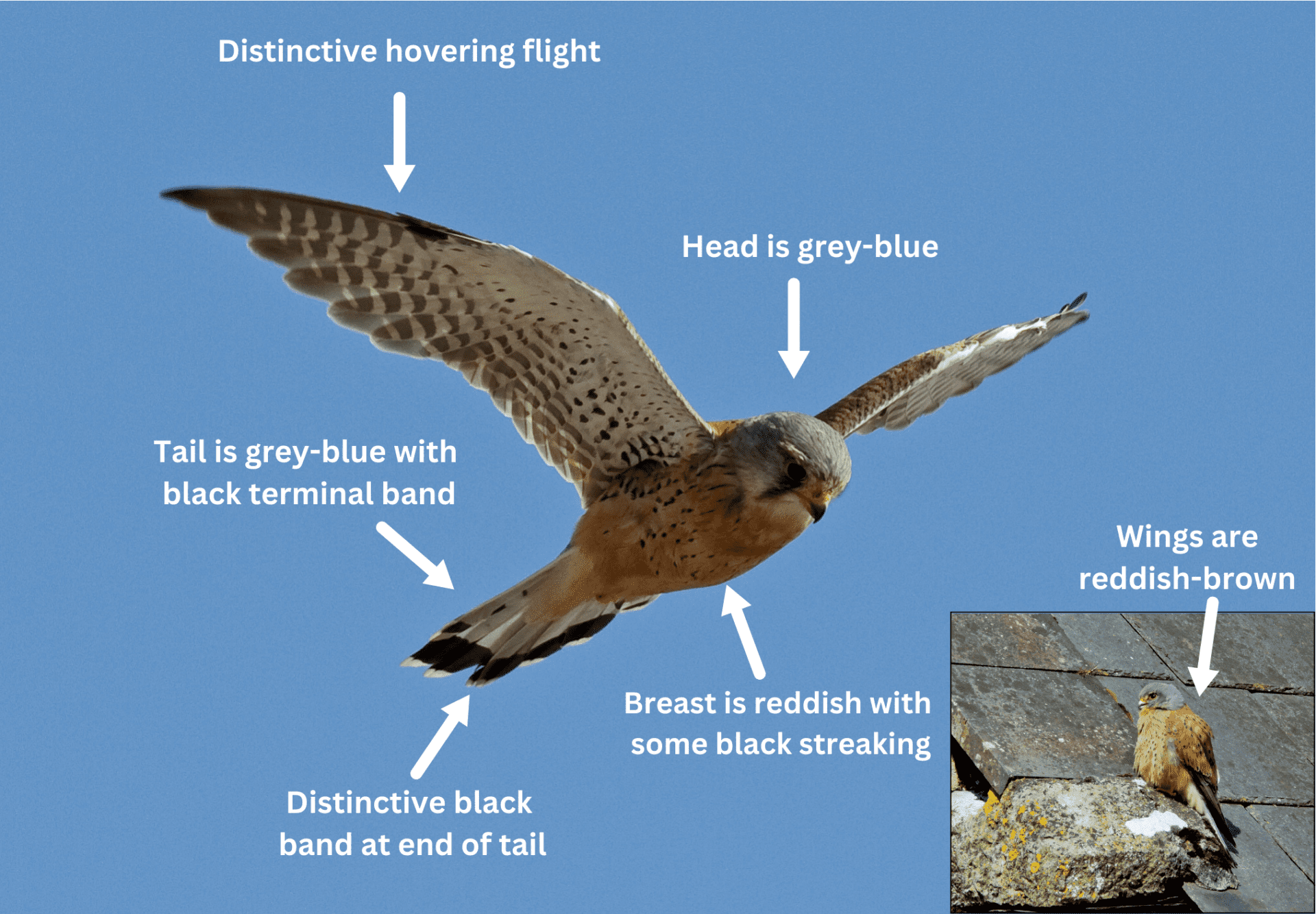

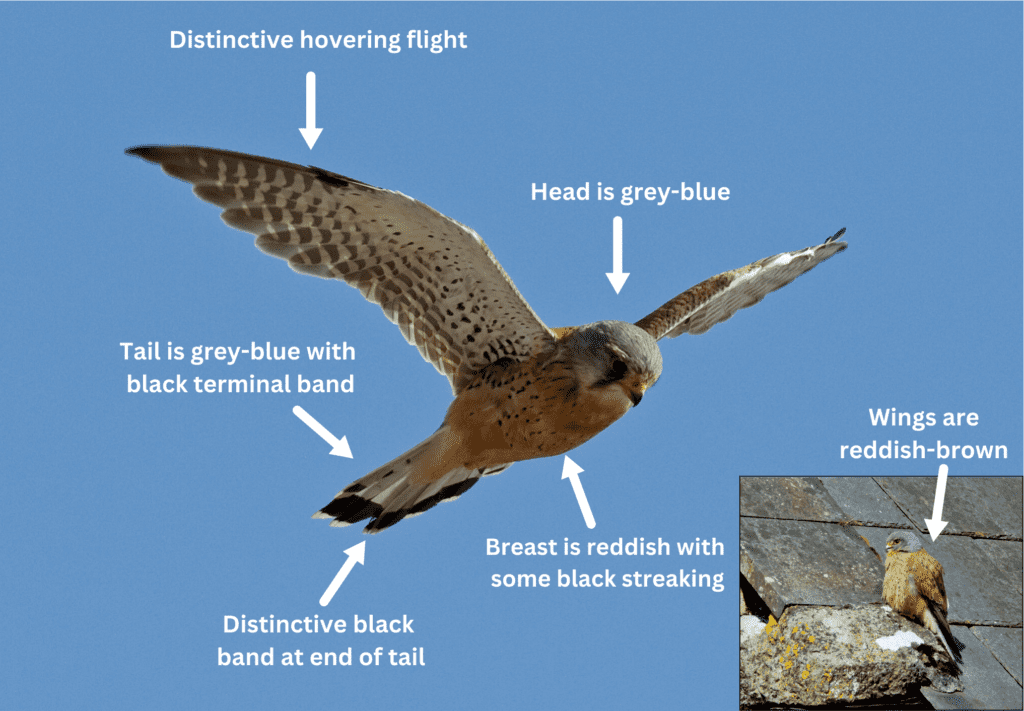

Male Common Kestrel hovering. (Shay Connolly – main photo; Dick Coombes – inset photo).

Male Common Kestrel hovering. (Shay Connolly – main photo; Dick Coombes – inset photo).

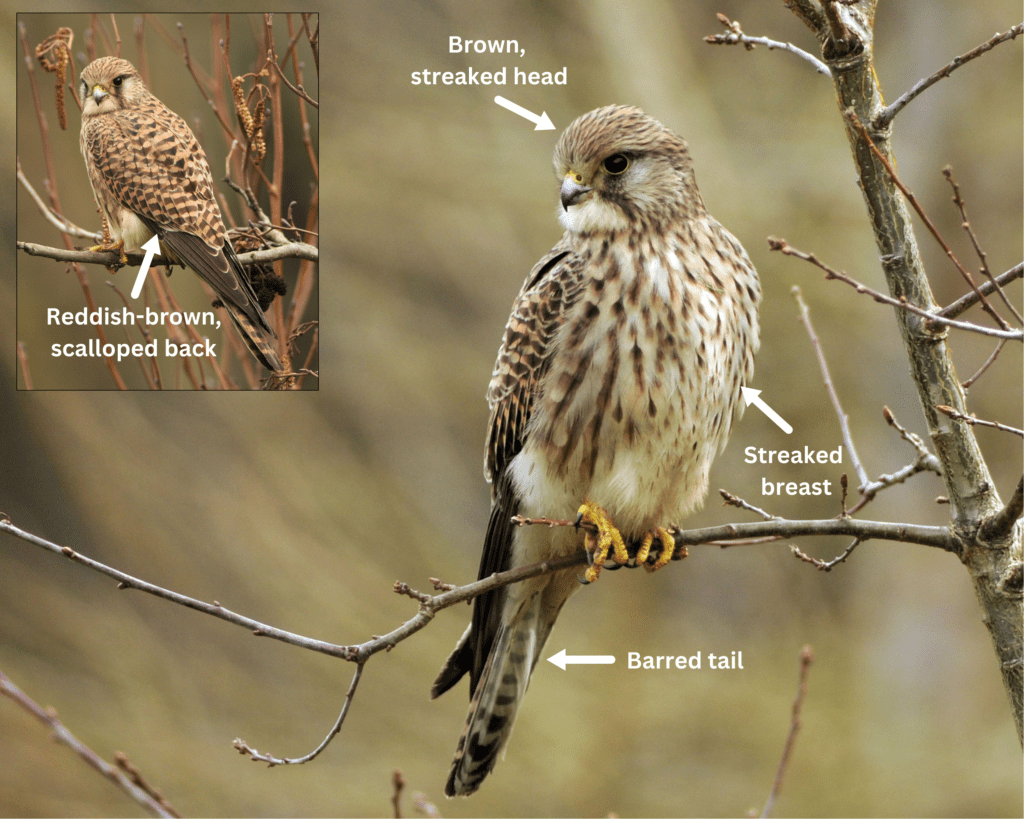

Female Comon Kestrel. (Michael Finn – both photos).

Female Comon Kestrel. (Michael Finn – both photos).

The Common Kestrel can be found in the rural, urban and suburban sites. Kestrels feed on insects and small rodents.

Male and female Common Kestrels are quite different from one another. The female is browner overall than the male and larger in size. The most distinctive feature of both sexes is the hovering flight they employ when hunting – the bird will hover in the air searching for prey on the ground, with the head tipped forward.

Once a wide-spread species, the population in Ireland is in free-fall and currently red-listed on the Birds of Conservation Concern of Ireland list, meaning it is threatened with extinction. The main driver of this decline in Ireland appears to be habitat loss and the associated knock-on effects.

Long-eared Owl

Long-eared Owl. (Thomas McDonnell).

Long-eared Owl. (Thomas McDonnell).

Juvenile Long-eared Owls. (Shay Connolly).

Juvenile Long-eared Owls. (Shay Connolly).

Long-eared Owls can be found in forests, stands of tress on arable land, tall hedgerows and in large parks with tree cover. They feed mainly on small rodents but will also take small birds.

They are typically active at night, dawn and dusk. The sexes are very similar, with the female slightly lighter in colour. The size of the population in Ireland is still unclear.

The chicks are very vocal, particularly as they get older and make a ‘squeaky gate’ call. Listen here.

Barn Owl

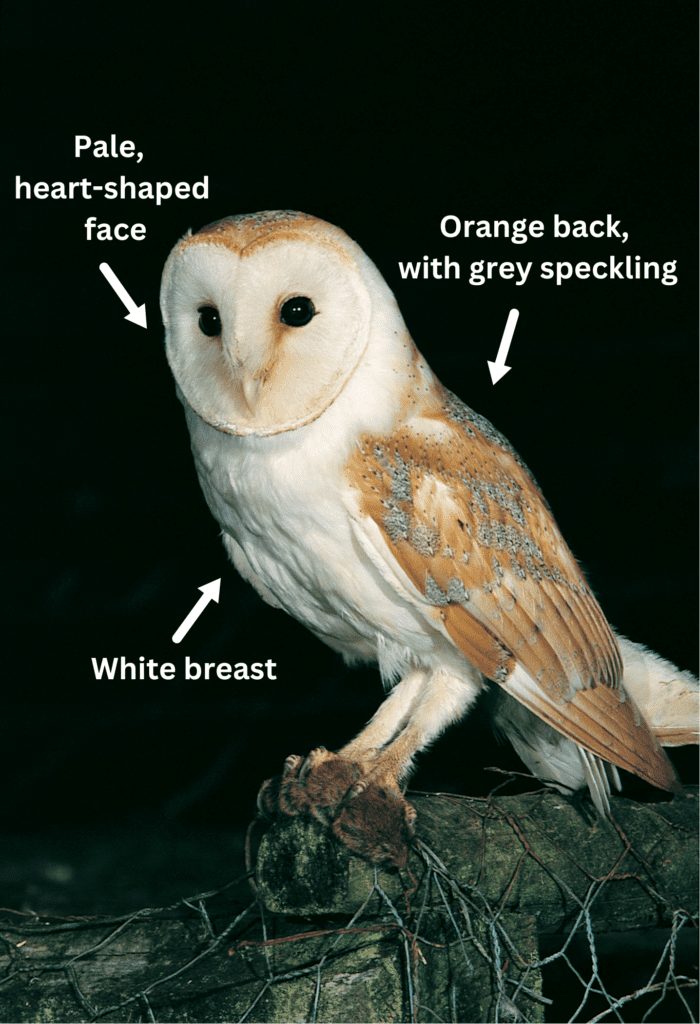

Barn Owl. (Mike Brown).

Barn Owl. (Mike Brown).

Barn Owl in flight. (Noel Marry).

Barn Owl in flight. (Noel Marry).

Typically active at night, the Barn Owl has a ghostly pale appearance and due to this and its shrieking call it has been associated with the Banshee in Ireland (the fox is another species whose call was attributed to the Banshee).

Barn Owls hunt mainly for rodents, but also for insects, using a perch to watch from before descending on their prey. They can be found in rural, urban and suburban settings, using forests and parks – preferably those with broadleaf trees. They’ll nest in trees, buildings and will easily use nest-boxes provided for them.

The Barn Owl was long considered the farmer’s friend as it is effective at keeping rodent populations under control. Indeed, when barns were being built, farmers placed a special window in the loft to encourage Barn Owls to nest in their yards.

Unfortunately, their population has been in trouble due to wide-scale use of rodenticide (rat poison) resulting in secondary poisoning. However, ongoing conservation work for this species in Ireland has seen positive results.

Now that you’ve gotten to grips with these species, don’t forgot to log your sightings here.

Many thanks!

Common Buzzard in flight. (Shay Connolly).

Common Buzzard in flight. (Shay Connolly). Common Buzzard. (Neil O’Reilly).

Common Buzzard. (Neil O’Reilly). Male Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Doyle – main photo; Kurt Kullman – inset photo).

Male Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Doyle – main photo; Kurt Kullman – inset photo). Female Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Ormond).

Female Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Ormond). Juvenile Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Doyle).

Juvenile Eurasian Sparrowhawk. (Tom Doyle). Peregrine. (Shay Connolly – main photo; Colum Clarke – inset photo).

Peregrine. (Shay Connolly – main photo; Colum Clarke – inset photo). Male Common Kestrel hovering. (Shay Connolly – main photo; Dick Coombes – inset photo).

Male Common Kestrel hovering. (Shay Connolly – main photo; Dick Coombes – inset photo). Female Comon Kestrel. (Michael Finn – both photos).

Female Comon Kestrel. (Michael Finn – both photos). Long-eared Owl. (Thomas McDonnell).

Long-eared Owl. (Thomas McDonnell). Juvenile Long-eared Owls. (Shay Connolly).

Juvenile Long-eared Owls. (Shay Connolly). Barn Owl. (Mike Brown).

Barn Owl. (Mike Brown). Barn Owl in flight. (Noel Marry).

Barn Owl in flight. (Noel Marry).