The Dublin City Riverbird Survey is back for its second year!

A huge thanks to everyone who has contributed to the project so far, we have received 80 records to date! These records will be published on the National Biodiversity Data Centre website. Please keep these records coming in – they can be logged here on the National Biodiversity Data Centre website.

In 2023, we published an id guide for the river bird species you’re most likely to come across in Ireland. To help you with your survey efforts, the Riverbird ID Guide has been reproduced below.

The species we are interested in are:

- Kingfisher

- Dipper

- Grey Wagtail

- Sand Martin.

Your records will greatly help the Dublin City Riverbird Survey, a project undertaken by BirdWatch Ireland and Dublin City Council as part of the Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan, with the online data portal provided by the National Biodiversity Data Centre.

Please do not disturb the nest site or nesting birds – photography or interference with a nest is against the law.

So, let’s get into it:

Kingfisher

Kingfisher (Michael Finn)

Kingfisher (Michael Finn)

ID

A stunning bird, the Common Kingfisher has an electric blue back and shoulders, a slightly darker blue on the crown and nape of the neck, and the wings. It is has a white throat and orange belly and cheek. Seems too tropical for Ireland, doesn’t it!

Unless you’re really lucky you probably won’t get more than a fleeting glimpse of electric blue as the bird zips along the waterway. Due to their speed and slightly cryptic nature, one of the handiest ways to id them is through their call.

Check out Common Kingfisher calls here on Xeno Canto – a free online, database of bird songs and calls from around the world, if you want to take a deeper dive into id.

Where to find them

Slow moving, clean waterways. Common Kingfishers mainly feed on small fish, but will also take insects.

Slow moving and unpolluted waterways have higher numbers of fish than fast and/or polluted waterways. Kingfishers perch on branches, posts, etc. along waterways keeping an out for fish which they dive for from the perch to retrieve. Thus they require plenty of places to perch.

Breeding

Common Kingfishers nest in burrows which they excavate themselves on vertical waterway embankments. They’re typically about 0.5m from the top of the embankment, and can measure up to about 1m in length, sloping upwards slightly to prevent rain entering the nest.

White-throated Dipper

White-throated Dipper (Colum Clarke main photo; Michael Finn inset photo)

White-throated Dipper (Colum Clarke main photo; Michael Finn inset photo)

ID

A handsome brown and white bird, slightly smaller than a blackbird. When perched it typically bobs up and down, and cocks its tail, in a way that is reminiscent of a wren.

Unusual for passerines (songbirds) in that it can swim and dive in running water. It propels itself underwater using its wings, and can also walk underwater!

Quite a shy bird, so again, knowing its song and call is useful (see here)

Where to find them

Along fast-flowing, stony rivers. Dippers feed mainly on aquatic insects but will also take small fish such as minnows. Dippers use exposed rocks as perches.

Breeding

Dippers nest within natural crevices, cracks in bridges, weirs and walls, and will readily use nest boxes provided they’re placed in a suitable location.

Both sexes build the nests, which are dome-shaped, and composed of moss, leaves and grass. The entrance to the nest is wide, and typically points down toward the water. The inside of the nest is lined with stems, hair and leaves.

Grey Wagtail

Grey Wagtail (Michael Finn)

Grey Wagtail (Michael Finn)

ID

Far more colourful than it’s name suggests, adult Grey Wagtails have a yellow belly and rump, and the latter is striking in flight. It has a grey head, back and shoulders.

During the breeding season, males have a black throat and females range from an all white throat to a greyish-black throat, with some white. Grey Wagtail legs are pink, while Pied Wagtails have black legs.

When flying the Grey Wagtail, has a distinctive up and down, undulating motion, (think of a wave-form), with the long tail a distinctive feature. When standing it constantly bobs its tail.

In flight it can be confused with its cousin the Pied Wagtail (willy wagtail), particularly at a distance/ in poor light conditions. Knowing the flight call is helpful in these instances (see here).

Where to find them

Typically found on small, fast-moving watercourses, with lots of exposed rocks for perches.

Prefers these waterways to be in woodland or tree-lined but can turn up on watercourses with less trees, particularly if commuting between sites.

Can turn up at lakes and slower moving watercourses. Feeds on insects.

Breeding

Breeds in rock crevices, cracks in stone bridges, nest boxes, etc., beside water.

Sand Martin

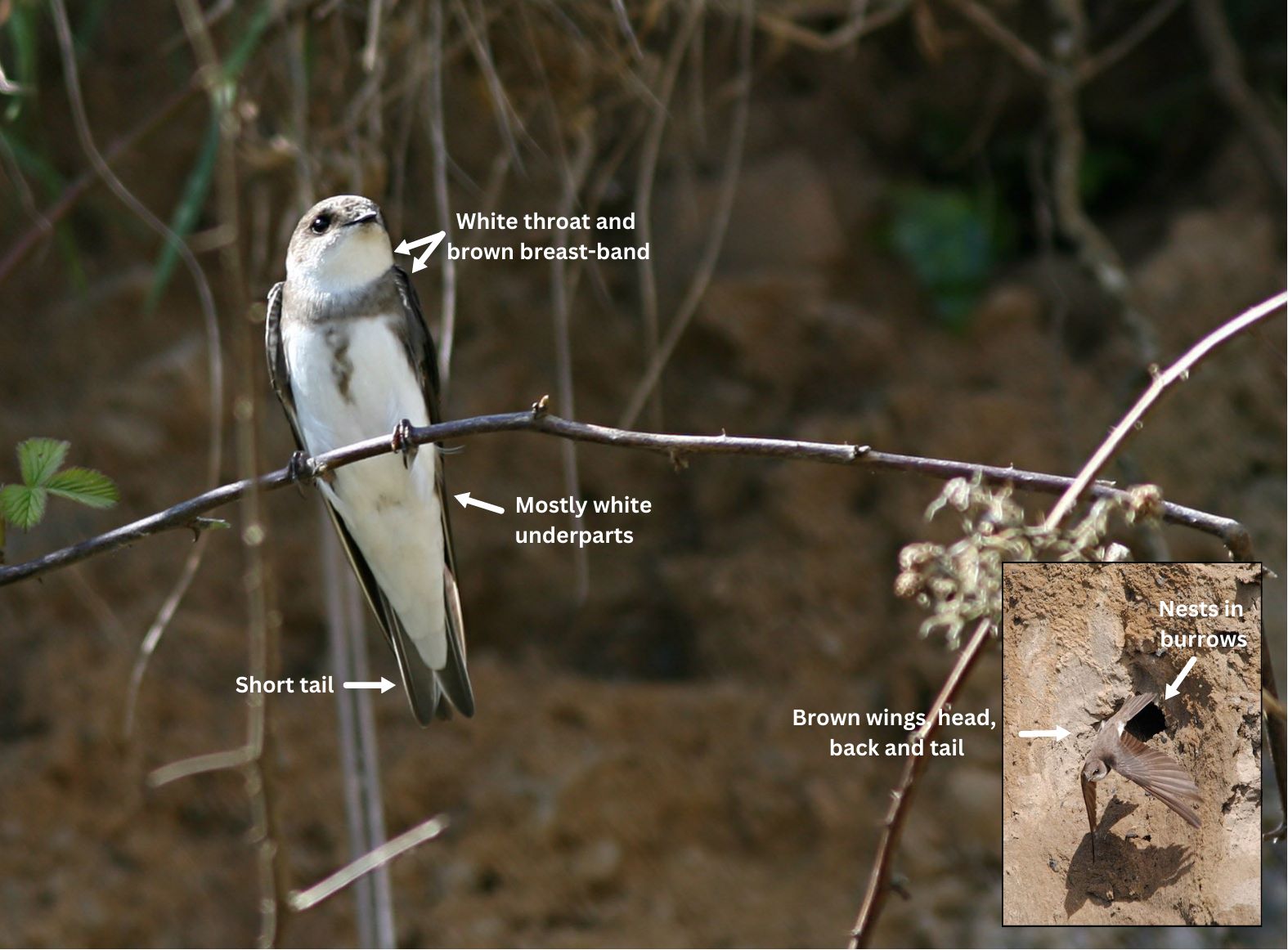

Sand Martin (Paddy Dwan main photo; Padraig Fogarty inset photo)

Sand Martin (Paddy Dwan main photo; Padraig Fogarty inset photo)

ID

The smallest member of the hirundine family (swallows and martins) to occur in Ireland.

It has a brown head, wings and back. The throat and belly are white, with a brown line dividing them. The tail is forked but not as long as a swallows tail.

The species most commonly confused with Sand Martins, are the House Martins. They have very similar shapes. However, the House Martin is blue and black above, with a white rump, and the belly and throat are completely white with no dividing line between them.

The Sand Martins call can be found here.

Where to find them

Sand Martins can be found on a variety of waterbodies, from rivers and canals, to lakes and ponds. They can even be found nesting in dune systems on beaches.

They are a summer visitor to Ireland, arriving from their wintering grounds in western Africa from approximately March and leaving again by October.

Breeding

Sand Martins are a social creature and nest in colonies in close proximity to waterbodies.

They dig burrows into sandy, vertical banks on rivers, by lakes, in quarries, even on beaches. They will also nest in drainpipes, crevices in stonework and in purpose-built man-made nesting structures.

Sand Martin nest site

The burrows can measure up to 1m in length and rise slightly upward to prevent rain accessing the nest. The same burrow can be used for several years.

Now you’re armed with an id guide and some additional info on these remarkable birds – the next step is to get out there, find them and report them back to us here!

Good luck!

Kingfisher (Michael Finn)

Kingfisher (Michael Finn) White-throated Dipper (Colum Clarke main photo; Michael Finn inset photo)

White-throated Dipper (Colum Clarke main photo; Michael Finn inset photo) Grey Wagtail (Michael Finn)

Grey Wagtail (Michael Finn) Sand Martin (Paddy Dwan main photo; Padraig Fogarty inset photo)

Sand Martin (Paddy Dwan main photo; Padraig Fogarty inset photo)