Cuckoo

| Irish Name: | Cuach |

| Scientific name: | Cuculus canorus |

| Bird Family: | Cuckoo |

green

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

Widespread summer visitor to Ireland from April to August.

Identification

Despite its obvious song, relatively infrequently seen. In flight, can be mistaken for a bird of prey such as Sparrowhawk, but has rapid wingbeats below the horizontal plane - i.e. the wings are not raised above the body. Adult male Cuckoos are a uniform grey on the head, neck, back, wings and tail. The underparts are white with black barring. Adult females can appear in one of two forms. The so-called grey-morph resembles the adult male plumage, but has throat and breast barred black and white with yellowish wash. The rufous-morph has the grey replaced by rufous, with strong black barring on the wings, back and tail. Juvenile Cuckoos resemble the female rufous-morph, but are darker brown above.

Voice

The song is probably one of the most recognisable and well-known of all Irish bird species. The male gives a distinctive “wuck-oo”, which is occasionally doubled “wuck-uck-ooo”. The female has a distinctive bubbling “pupupupu”. The song period is late April to late June.

Diet

Mainly caterpillars and other insects.

Breeding

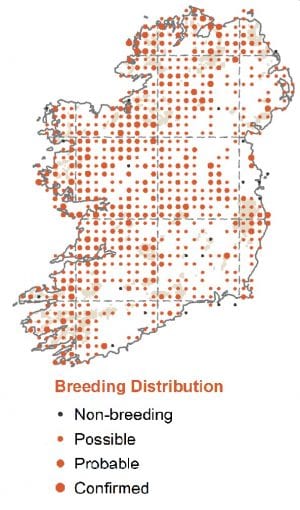

Widespread in Ireland, favouring open areas which hold their main Irish host species – Meadow Pipit. Has a remarkable breeding biology unlike any other Irish breeding species.

Wintering

Cuckoos winter in central and southern Africa.

Monitored by

Countryside Bird Survey

Blog posts about this bird

New video showcases conservation efforts bringing life back to a Galway Bog

Galway's Living Bog

The future of Carrownagappul Bog, like so many other raised bogs, was one of continuing deterioration. Through collective efforts to restore the bog, which have been embraced by local communities, the future of the site now looks very different. A new video by BirdWatch Ireland and Galway County Council, and funded through the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, called ‘Life on the bog’ showcases the rich biodiversity of Carrownagappul, the wildlife that is slowly returning to the bog and the efforts to restore this special site. [embed]https://youtu.be/CPXxIxnplq8[/embed] We often only appreciate something once we lose it. We have come dangerously close to this situation when it comes to our bogs, but thankfully this is changing. Our relationship with ‘the bog’ in Ireland has been mostly one of under-appreciation and over-exploitation. For many people, the word ‘bog’ still brings with it negative connotations, and conjures images of an unproductive, dark place that is devoid of life – nothing could be further from the truth. Collectively, it seems there is a slow awakening to the true beauty, rich biodiversity and unique nature of these special habitats, and an understanding of the vital role they play in all of our lives - it only took us a few thousand years!Carrownagappul Bog SAC, near Mountbellew in east Galway is one of the largest remaining, relatively intact raised bogs in the country. The 325 hectare bog, is currently undergoing restoration - as well as a rebirth in the minds of the local community. Like so many bogs across the country, Carrownagappul Bog SAC was drained, dried out and degraded. With turf-cutting at an end on the site, communities surrounding Mountbellew are starting to embrace a new future for the bog, one which realises its significant potential for biodiversity and carbon storage as well as an amenity for locals.

Carrownagappul Bog © John Lusby

A number of different groups, from very different backgrounds have come together for the same purpose, to restore and protect Carrownagappul Bog, and part of this has involved raising awareness of the importance of the bog and encouraging people to come and appreciate it for themselves. Marie Mannion, Heritage Officer with Galway County Council, commented ‘it is amazing what can be achieved when we work together and highlighting the richness, heritage and beauty of our bogs.’ Paul Connaughton has been influential in helping to change local mindsets towards the bog, just has his own has changed, he commented ‘I have been visiting the bog and cutting turf on the bog all my life, I find it amazing that you can be so familiar with a place yet only know a certain side of it, I have to admit, despite visiting the bog all my life, it is only recently that my eyes have been opened to the wildlife that lives on the bog’. We are now working to ensure that the natural beauty of the flora and fauna will be restored and preserved to be enjoyed by many generations to come’. The ‘Living Bog Project’ has worked to restore twelve raised bogs in the midlands, which includes Carrownagappul Bog SAC, where over 3,000 dams were installed across a vast network of open drains. The restoration works have focused on rewetting the bog to allow the growth of sphagnum mosses – the building block of the bog. Ronan Casey, Public Awareness Manager with The Living Bog Project, commented ‘Restoring a bog is only part of the equation. We are restoring Carrownagappul for biodiversity but also for local water quality and the planet. The carbon storage potential of sites like this is immense. But one of the biggest and best things about this bog has been the involvement of the local community. The is perhaps the most accessible bog in the country, thanks to its past uses, and its future as a community amenity is all down to the locals, who have designed some brilliant walking loops, trails and facilities at which generations to come can marvel at the wildlife which has been returning to this protected bog since restoration works began in 2017.”Peat dam at Carrownagappul Bog © John Lusby

BirdWatch Ireland have also come on board and worked with Galway County Council and Galway Telework to undertake a survey of the breeding birds on the bog, which recorded forty breeding bird species. John Lusby commented ‘although I am from Galway, I wasn’t very familiar with Carrownagappul before I first set foot on the bog, but I remember distinctly the first time I did, it was very early on a spring morning as the sun was coming up, and the first thing that struck me was the dawn chorus, which was simply spectacular. The bog was alive with the sound of Snipe drumming, Cuckoo calling, Red Grouse, and many other birds competing to be heard. It is a special place and we are very lucky that we didn’t loose it, it will take time to see the benefits of the restoration works, but the future is exciting, and such a dramatic change from its recent past’.

BirdWatch Ireland, Galway County Council with help from Galway Telework, The Living Bog Project and MKO, also ran a nature camp at Carrownagappul Bog, which brought local children out onto the bog with scientists to get down and dirty and explore the wonders and the wildlife of the bog. Through hands on activities the children learned about how the bog was formed, the depth and age of the peat under their feet, the water retention qualities of sphagnum mosses, and the many specially adapted plants that live on the bog, including insectivorous plants! As well as some of the birds and mammals that depend on the bog, including up close encounters with some of these! Marie Mannion, commented ‘not only was it an opportunity for the children to become aware and know about the amazing place their local bog is also was a revelation to their parents on this hidden heritage gem that is on their doorstep’.

Marsh Fritillary © Cathal Forkan

Galway County Council and BirdWatch Ireland, teaming up with The Living Bog Project and Galway Telework have developed a range of education materials on Carrownagappul Bog. A video called ‘Life on the Bog’ showcases the wildlife on the bog, and documents the recent history and restoration works on Carrownagappul Bog. John Lusby commented, ‘It is very easy to take a place like this for granted, and that is exactly what we have done with so many bogs like it that are now lost. When you take the time to look properly and to appreciate just how complex these habitats are and the diversity of life they support then you will be rewarded. We only captured a small glimpse of the wildlife on Carrownagappul Bog in the video, but I hope it gives a sense for just what is here and also what is possible when people come together to protect what is important’.

Sundew - an insectivorous plant adapted for life on the bog © Cathal Forkan

This project was an action of the Galway County Heritage and Biodiversity Plan 2017-2022, with funding provided through the National Biodiversity Action Plan, National Parks & Wildlife Service, from the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage and Galway County Council. The video ‘Life on the bog’ was filmed and edited by Crow Crag and is being released in conjunction with ‘Worlds Wetlands Day 2021’ and is available here: Life on the bog and on the Galway Community Heritage website