Greenland White-fronted Goose

| Irish Name: | Gé Bhánéadanach |

| Scientific name: | Anser albifrons flavirostris |

| Bird Family: | Geese |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

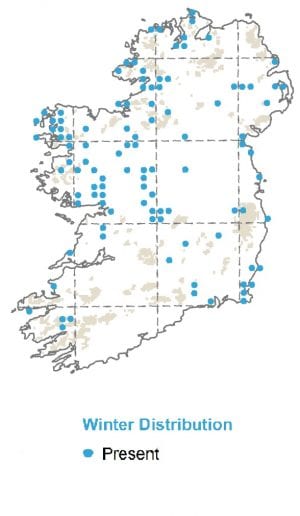

Scarce winter visitor to wetlands in Wexford and western Ireland from October to April.

Identification

Medium-sized grey goose, with orange legs, a long orange-yellow bill with a prominent blaze around the base of the bill (adults).

Voice

High-pitched, musical in quality (not nasal). Usually disyllabic.

Diet

Grazes on a range of plant material taking roots, tubers, shoots and leaves. Grasses, clover, spilt grain, winter wheat and potatoes are popular foods. Forages over peat bogs, dune grassland, and occasionally salt marsh, with the use of agricultural grassland increasing in recent years.

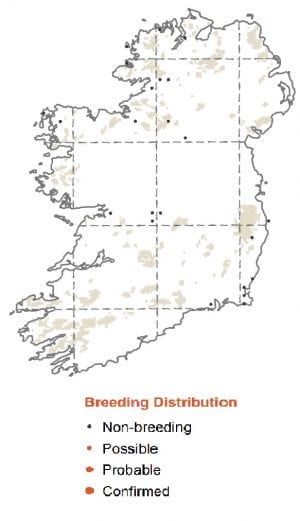

Breeding

Breeds on lowland tundra, often by lakes and rivers. Nests are widely scattered, though loose colonies may be formed.

Wintering

Winters in Ireland and Scotland. Highly gregarious. Traditionally occurred in peatland areas, though now mostly seen feeding on intensively managed grasslands

Monitored by

National Parks and Wildlife Service/ Greenland White-fronted Goose Study Group.

Blog posts about this bird

World Migratory Bird Day campaign underscores the importance of insects and shines a light on declines

Saturday, October 12th marks World Migratory Bird Day. By focusing their 2024 campaign on insects, organisers hope to underscore their importance to migratory birds while also highlighting wider concerns related to decreasing insect populations.

The importance of insects for migratory birds and all life

We often hone in on the long distances travelled by migratory bird species and rightly so. It is extremely impressive that such small creatures can fly thousands of miles, often in challenging weather conditions, and arrive at their destination safely. However, many birds are reliant on other species to make this journey possible. Indeed, it is the existence of other winged creatures – insect populations – that gives them the fuel to keep on going.

Insects are essential food sources for many migratory birds on their long journeys, and some species will time their migrations to align with periods of insect abundance in their stopover locations. Once they replenish their energy reserves, they can resume their journey.

Species such as warblers, flycatchers, swallows, and swifts are particularly reliant on insects. However, many other bird species such as ducks and shorebirds depend on insects during migration and at other stages in their lifecycle, in particular for raising their young before they are able to fly.

On a wider level, insects provide critical ecosystem services that support all life on this planet. They pollinate crops which supports food production, decompose waste materials and contribute to nutrient cycling and soil fertility, and control pests. Their decline has a direct impact on ecosystem functioning.

Insect Declines

Many people will recall how, not so long ago, a large number of dead insects would be found on a car windscreen and bumper following a drive through the countryside. Those too young to have experienced this period of insect abundance are likely to have heard this anecdote from friends and family. In fact, it is such a widely shared observation that it has become known to entomologists as the “the windshield phenomenon”.

Anecdotally, insects have experienced declines, but what does the science say? Unfortunately, invertebrates including insects have been historically understudied and many gaps in the data still remain. Additionally, where assessments have taken place, they have predominantly been in regions that can afford to fund insect science such as Europe and North America. Some of the most biodiverse regions on the planet have had little to no assessments of their insect populations. This lack of data on the species we know, coupled with the fact that millions of insect species are yet to be discovered, suggests that we don’t have the full picture on the scale of global insect decline.

However, in recent decades, efforts to better understand how insects are faring have expanded with pollinating insects such as bees, hoverflies, butterflies and moths in particular becoming the subject of an increased amount of research. From what we know so far, the situation is clear: they are in peril.

For example, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) European Red List of Bees shows that 9% of the 1,965 species of bee in Europe are Threatened with extinction mainly due to habitat loss as a result of agriculture intensification, urban development, increased frequency of fires and climate change. A further 5.2% are considered Near Threatened. However, a staggering 56.7% of these species were classified as “Data Deficient” meaning that there is not enough data to evaluate their risk of extinction.

Over 37% of the European hoverfly species assessed in the IUCN European Red List of Hoverflies were considered Threatened, with a further 6.9% considered Near Threatened. One species that previously occurred in Sweden, Finland and possibly Poland, was classified as Regionally Extinct.

As outlined in their Red List Strategic Plan (2021-2030), the IUCN is working to substantially increase the number of wild species assessed, particularly plants, invertebrates and fungi.

Insects in Ireland

In Ireland, the National Biodiversity Data Centre is doing trojan work to improve our knowledge of insect populations in Ireland, particularly via monitoring schemes for butterflies, bumblebees and more recently, dragonflies.

The Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme, established by the Data Centre in 2008, is Ireland’s longest-running citizen science insect monitoring scheme. By tracking changes in 15 species, we now know that overall butterfly populations have declined by 55% since 2008.

Meanwhile, the All-Ireland Bumblebee Monitoring Scheme has been tracking changes in the populations of the eight most common bumblebee species since 2012. The current overall trend from 2012-2023 is a year-on-year decline of 3.3%.

Celebrate World Migratory Bird Day

World Migratory Bird Day is an annual global campaign dedicated to raising awareness of migratory birds and the need for international cooperation to conserve them. It is organised by a collaborative partnership among two UN treaties – the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement (AEWA) – and the non-profit organisation, Environment for the Americas (EFTA).

The return of winter migrants to Ireland brings a seasonal spectacle as thousands of birds, such as Whooper Swans, Greenland White-fronted Geese and Greylag Geese arrive from colder northern regions. This annual migration highlights Ireland's role as a vital sanctuary, providing essential habitats for these species during the harsher winter months. Keep an eye out for some of these species this World Migratory Bird Day but be sure to keep your distance to avoid harmful disturbance.

This year’s insect theme may also encourage you to play your part for Ireland’s insect populations. One way you can do this is by getting involved in the National Biodiversity Data Centre’s citizen science initiatives. Find out more here.

Geese and Swans return to Ireland for the winter

If you haven't noticed the dearth of swifts and swallows around the country recently, then this weeks weather will have put it beyond doubt that the summer is indeed over! When most people think of "birds flying south for the winter" they associate it with a mass exodus of Swallows, Martins, Swifts, Warblers and Terns (amongst others), but don't forget that it also means an influx of over 50 waterbird species from northerly latitudes into Ireland for the winter! In the last few weeks the first reports of our wintering goose and swan species have been filtering in, and here in BirdWatch Ireland we love this time of year!

See below some of the details about our Goose and Swan species that have arrived in Ireland in recent weeks:

The first Greenland White-fronted Geese of winter 2019/20 arrived on the North Slob in Wexford yesterday (01 October 2019) - four adults and a juvenile.

The Greenland White-fronted Goose is the species on the BirdWatch Ireland logo. If you want to get a good look at this species, make sure you visit Wexford Wildfowl Reserve this winter. Later this month there will be a number of public events for their annual 'Goose Week' and they will also be celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the reserve.

The first Greenland White-fronted Geese of winter 2019/20 arrived on the North Slob in Wexford yesterday (01 October 2019) - four adults and a juvenile.

The Greenland White-fronted Goose is the species on the BirdWatch Ireland logo. If you want to get a good look at this species, make sure you visit Wexford Wildfowl Reserve this winter. Later this month there will be a number of public events for their annual 'Goose Week' and they will also be celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the reserve.

The first Brent records of 2019 came at the end of August, which isn't actually unusual, though the bulk of birds arrived several weeks later (and are still coming!).

When they first arrive in Ireland they head en mass for Strangford Lough. After refueling there, they gradually disperse around the Irish coast as the winter goes on. Many Brent have already returned to their usual haunts in Donegal, Derry, Louth and Dublin, where they'll feed on eelgrass and algae in the sea, before turning to terrestrial grasslands for a few months before making the return journey back to Canada!

The first Brent records of 2019 came at the end of August, which isn't actually unusual, though the bulk of birds arrived several weeks later (and are still coming!).

When they first arrive in Ireland they head en mass for Strangford Lough. After refueling there, they gradually disperse around the Irish coast as the winter goes on. Many Brent have already returned to their usual haunts in Donegal, Derry, Louth and Dublin, where they'll feed on eelgrass and algae in the sea, before turning to terrestrial grasslands for a few months before making the return journey back to Canada!

One of the first records in Ireland this year was via the WWT's Kane Brides who informed us of a satellite-tagged bird that arrived from Iceland on the 4th of September, spending a couple of hours in Roscommon before heading to Carlingford Lough on the east coast that night.

Small numbers of Pink-footed Geese winter in Ireland, but hundreds of thousands winter in the UK and stop in Ireland en route from their Icelandic breeding grounds. Since the start of September there have been loads of Pink-foots (Pink-feets?!) spotted in Donegal and smaller flocks in Wexford, Louth and Dublin.

One of the first records in Ireland this year was via the WWT's Kane Brides who informed us of a satellite-tagged bird that arrived from Iceland on the 4th of September, spending a couple of hours in Roscommon before heading to Carlingford Lough on the east coast that night.

Small numbers of Pink-footed Geese winter in Ireland, but hundreds of thousands winter in the UK and stop in Ireland en route from their Icelandic breeding grounds. Since the start of September there have been loads of Pink-foots (Pink-feets?!) spotted in Donegal and smaller flocks in Wexford, Louth and Dublin.

In the last few days there have been multiple reports of large flocks of Greylag Geese at coastal sites in Donegal.

Greylags are a tricky one - we have a resident population that breeds here, but we also get migrants from Iceland for the winter too. And there's no way to tell which is which in the field as they look the exact same! Donegal has many feral/naturalised Greylag Geese, but some of those recent large flocks probably have some Icelandic-migrants mixed in too.

Barnacle Geese

In the last few days there have been multiple reports of large flocks of Greylag Geese at coastal sites in Donegal.

Greylags are a tricky one - we have a resident population that breeds here, but we also get migrants from Iceland for the winter too. And there's no way to tell which is which in the field as they look the exact same! Donegal has many feral/naturalised Greylag Geese, but some of those recent large flocks probably have some Icelandic-migrants mixed in too.

Barnacle Geese

The first 'Barnies' of the season touched down in Donegal at the start of this week.

This species prefers coastal grasslands and offshore islands in the west and north-west. Because of the remote locations they use, the NPWS recently carried out a Barnacle Goose census by plane!

The first 'Barnies' of the season touched down in Donegal at the start of this week.

This species prefers coastal grasslands and offshore islands in the west and north-west. Because of the remote locations they use, the NPWS recently carried out a Barnacle Goose census by plane!

Whooper Swan

The first definite migrants have only appeared in recent days - in Donegal, Derry and today in Wexford.

In the last census, there were nearly 12,000 Whooper Swans in ROI and >3,500 in NI. The I-WeBS office in BirdWatch Ireland, together with our colleagues in Northern Ireland and further afield, will be coordinating another census of Whooper Swans in January 2020 so please keep an eye on your local flock as the winter progresses!

So there you have it - thousands of geese and swans are currently migrating from Iceland, Greenland and Canada to spend the winter in Ireland! Many of these species are of conservation concern and we're lucky to have the wetlands to support them, so do keep an eye out for them in your area as the winter goes on!

Greenland White-fronted Goose

The first Greenland White-fronted Geese of winter 2019/20 arrived on the North Slob in Wexford yesterday (01 October 2019) - four adults and a juvenile.

The Greenland White-fronted Goose is the species on the BirdWatch Ireland logo. If you want to get a good look at this species, make sure you visit Wexford Wildfowl Reserve this winter. Later this month there will be a number of public events for their annual 'Goose Week' and they will also be celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the reserve.

The first Greenland White-fronted Geese of winter 2019/20 arrived on the North Slob in Wexford yesterday (01 October 2019) - four adults and a juvenile.

The Greenland White-fronted Goose is the species on the BirdWatch Ireland logo. If you want to get a good look at this species, make sure you visit Wexford Wildfowl Reserve this winter. Later this month there will be a number of public events for their annual 'Goose Week' and they will also be celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the reserve.

Light-bellied Brent Goose

The first Brent records of 2019 came at the end of August, which isn't actually unusual, though the bulk of birds arrived several weeks later (and are still coming!).

When they first arrive in Ireland they head en mass for Strangford Lough. After refueling there, they gradually disperse around the Irish coast as the winter goes on. Many Brent have already returned to their usual haunts in Donegal, Derry, Louth and Dublin, where they'll feed on eelgrass and algae in the sea, before turning to terrestrial grasslands for a few months before making the return journey back to Canada!

The first Brent records of 2019 came at the end of August, which isn't actually unusual, though the bulk of birds arrived several weeks later (and are still coming!).

When they first arrive in Ireland they head en mass for Strangford Lough. After refueling there, they gradually disperse around the Irish coast as the winter goes on. Many Brent have already returned to their usual haunts in Donegal, Derry, Louth and Dublin, where they'll feed on eelgrass and algae in the sea, before turning to terrestrial grasslands for a few months before making the return journey back to Canada!

Pink-footed Goose

One of the first records in Ireland this year was via the WWT's Kane Brides who informed us of a satellite-tagged bird that arrived from Iceland on the 4th of September, spending a couple of hours in Roscommon before heading to Carlingford Lough on the east coast that night.

Small numbers of Pink-footed Geese winter in Ireland, but hundreds of thousands winter in the UK and stop in Ireland en route from their Icelandic breeding grounds. Since the start of September there have been loads of Pink-foots (Pink-feets?!) spotted in Donegal and smaller flocks in Wexford, Louth and Dublin.

One of the first records in Ireland this year was via the WWT's Kane Brides who informed us of a satellite-tagged bird that arrived from Iceland on the 4th of September, spending a couple of hours in Roscommon before heading to Carlingford Lough on the east coast that night.

Small numbers of Pink-footed Geese winter in Ireland, but hundreds of thousands winter in the UK and stop in Ireland en route from their Icelandic breeding grounds. Since the start of September there have been loads of Pink-foots (Pink-feets?!) spotted in Donegal and smaller flocks in Wexford, Louth and Dublin.

Greylag Geese

In the last few days there have been multiple reports of large flocks of Greylag Geese at coastal sites in Donegal.

Greylags are a tricky one - we have a resident population that breeds here, but we also get migrants from Iceland for the winter too. And there's no way to tell which is which in the field as they look the exact same! Donegal has many feral/naturalised Greylag Geese, but some of those recent large flocks probably have some Icelandic-migrants mixed in too.

Barnacle Geese

In the last few days there have been multiple reports of large flocks of Greylag Geese at coastal sites in Donegal.

Greylags are a tricky one - we have a resident population that breeds here, but we also get migrants from Iceland for the winter too. And there's no way to tell which is which in the field as they look the exact same! Donegal has many feral/naturalised Greylag Geese, but some of those recent large flocks probably have some Icelandic-migrants mixed in too.

Barnacle Geese

The first 'Barnies' of the season touched down in Donegal at the start of this week.

This species prefers coastal grasslands and offshore islands in the west and north-west. Because of the remote locations they use, the NPWS recently carried out a Barnacle Goose census by plane!

The first 'Barnies' of the season touched down in Donegal at the start of this week.

This species prefers coastal grasslands and offshore islands in the west and north-west. Because of the remote locations they use, the NPWS recently carried out a Barnacle Goose census by plane!

Whooper Swan

The first definite migrants have only appeared in recent days - in Donegal, Derry and today in Wexford.

In the last census, there were nearly 12,000 Whooper Swans in ROI and >3,500 in NI. The I-WeBS office in BirdWatch Ireland, together with our colleagues in Northern Ireland and further afield, will be coordinating another census of Whooper Swans in January 2020 so please keep an eye on your local flock as the winter progresses!

So there you have it - thousands of geese and swans are currently migrating from Iceland, Greenland and Canada to spend the winter in Ireland! Many of these species are of conservation concern and we're lucky to have the wetlands to support them, so do keep an eye out for them in your area as the winter goes on!

Each winter we monitor Ireland's waterbird populations through I-WeBS - a survey coordinated by BirdWatch Ireland, funded by the National Parks and Wildlife Service, and carried out by a network of bird surveyors who volunteer their time and expertise.

The I-WeBS office is interested in any records of Greylag or Pink-footed Geese this winter - please email us at iwebs@birdwatchireland.ie with numbers, locations and dates.

The website 'IrishBirding' was also a useful source for this article.