Last Sunday, 20th November, COP27, the 27th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), drew to a close in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. The Conference’s final agreement text, which each year sets out the Parties’ agreed actions to address climate change and its impacts, has included some potentially promising elements, but yet again, has critically ignored the main driver of climate change.

COP has been criticised for its lack of tangible outcomes over the years. It is, after all, the 27th time global leaders have met to discuss international action on climate change, and it is difficult to see what real and commensurate action has come out of the negotiations. This year’s COP was dubbed the ‘Implementation COP’ by the Egyptian Presidency who laid out the ambition to “showcase unity against an existential threat that we can only overcome through concerted action and effective implementation”. In addition to this, 2022 has been called the ’Year of the Ocean’, and many anticipated the “Blueing” the Paris Agreement at COP27.

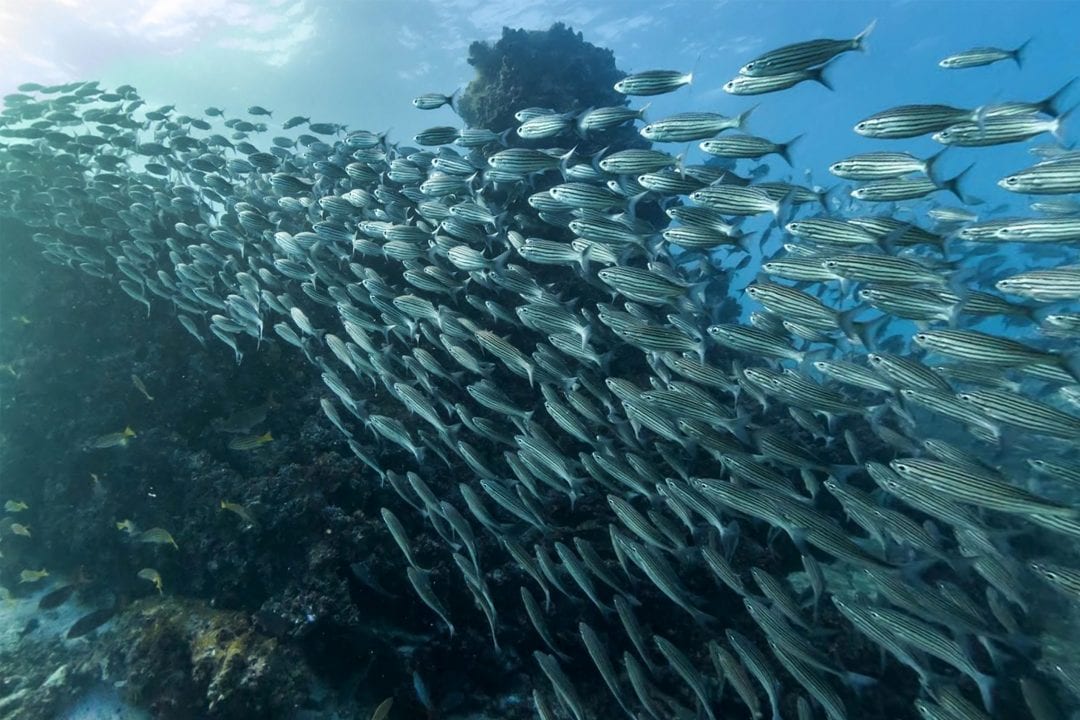

This year, COP’s Blue Zone (the conference’s space for UN Accredited delegates and organisations) included its first ever Ocean Pavilion, there were over 300 ocean-related events, and several declarations and the final text recognised the fundamental role of the planet’s beating blue heart in our climate system, and in its role as one of our greatest allies in addressing climate change.

Recognising the importance of our one global ocean is also critical in connecting the already occurring and devastating impacts of climate change, to the political inertia of faraway and historically high-emitting nations. Unless we tackle the climate emergency at its source, that is at emissions level, the reality for coastal communities globally is that the ocean, while being a source of livelihood for many, is also a source of many threats. For climate-vulnerable countries and small island states, this COP needed to deliver a ‘three-legged stool’ of climate action comprised of mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage.

Loss & Damage

Loss and Damage covers all those impacts of climate change that we can no longer avoid or adapt to; everything from the rapid onset events such as flooding and tidal surges that destroy homes and crops, and contaminate drinking water, to the most incomprehensible and slower onset scenarios. For small island states and coastal communities this will, in the not-too-distant future, mean the loss of entire communities engulfed by the sea.

The plight of ocean communities in climate vulnerable nations has long since been sidelined by historically high-emitting countries, who have prioritised short-term economic interests over solidarity with climate vulnerable nations. Indeed, the need to recognise the unjust nature of climate impacts and provide for Loss and Damage dates to before the creation of the UNFCCC in 1992. Just last year Tuvalu’s Foreign Minister, Simon Kofe, delivered his speech to COP26 from a podium in knee-deep seawater to draw attention to rising sea levels and the “real-life situations faced in Tuvalu” because of climate change.

Tuvalu’s Foreign Minister, Simon Kofe, delivering his COP26 statement. Photo: Tuvalu Foreign Ministry/Reuters

During COP27 An Taoiseach, Micheál Martin, committed to providing €10 million euro to the Global Shield initiative. However, this insurance-based initiative available for climate disasters in low-income countries, has drawn criticism for distracting from the central demand of establishing a dedicated Loss and Damage fund. An insurance-based scheme is wholly inappropriate to address the impacts of climate change for these countries. At the most basic level, insurance provides for a risk of something that might happen, not something that will happen.

Minister Eamon Ryan, who was EU Ministerial Representative on Loss and Damage in the final days of COP27, has stated that reliance on one funding mechanism such as the Loss and Damage mechanism, can be problematic in terms of delivering false promises and in terms of the lengthy period of time needed to establish it. The final text of the COP27 agreement does not specify the details of how the Loss and Damage mechanism will work and that detail is to be worked out in advance of COP28. It is essential that the details of this programme are not delayed further past this point, as the Global Shield Initiative, which may be an important interim measure, is inadequate and unsuitable in the long term for the purposes of Loss and Damage.

Failure to act on fossil fuel extraction and consumption

However, the most insulting and undermining failure of all COPs, not just this ‘implementation COP’, is that the phasing out of fossil fuels, that is addressing the root cause of climate change, has yet to be included in the final decision texts. COP27’s statement restated last year’s pledge to accelerate “efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”.

Progress was made at this year’s COP through expanded support for the Global Offshore Wind Alliance (which now includes support from Belgium, Colombia, Germany, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, the UK and the US) that was founded at COP26 in Glasgow, but there has been less focus on reducing harmful energy production. The Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA) which calls for an acceleration in the transition away from fossil fuel dependency and was also established at COP26, increased its membership by just three. This is a long way short of the entire list of Parties to the UNFCCC. Without removing the root cause of climate change, the ongoing loss and damage, that is the ongoing commitment to climate-related death warrants, is set to continue.

Furthermore, the EU announced that it was ready to increase its emissions reduction target from 55% to 57% at COP27, but this doesn’t go nearly far enough to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C by 2030. Emissions reductions of 65%, not including carbon sinks, is needed for the EU to stay in line with the 1.5°C limit.

Just Transition and Just Existence

Decarbonising our society and economy is far from a simple task. However, the fact that we can even discuss how a Just Transition will happen in Ireland is a luxury that many of our global ocean neighbours have not been afforded. Island states have to ask that their Just Existence be considered alongside a Just Transition in historically high-emitting countries. As Dr. Satyendra Prasad, Fiji’s Ambassador to the United Nations stated “We are absolutely, fully supportive of a just transition. All we are asking is that there should be fairness and there should be pace and speed in the transition. But we also ask you to please also understand our just existence. Fairness demands that just transition and just existence are seen equally and not that one is superior to the other.”

For climate vulnerable communities, their just existence depends on our actions. We need to ensure that in protecting our seas here in Ireland, we incorporate measures that will also protect our global ocean and neighbours. We need our politicians in historically high-emitting countries to tackle the root cause of climate change and end the extraction and production of fossil fuels, if any commitment to Loss and Damage is to be meaningful. And we need our politicians to make good on the progress for the ocean made in the final text of COP27 and to incorporate ocean-based action in our national climate goals. As Mary Robinson has quite rightly pointed out, the world remains on the brink of climate catastrophe and communities around our global ocean are among the many experiencing the worst effects of this emergency.

Don’t forget to sign up to the Fair Seas newsletter for the latest ocean updates, actions and events.