For the last couple of months, the number and diversity of birds in your garden mightn’t have been particularly high, but you’ll see a considerable increase in the coming weeks. That does beg the question of where have your garden birds been until now? And how far do they travel away from your garden?

Over the summer, birds are restricted to a tight radius around their nest. There are no such restrictions outside the breeding season though, and though some species never feel the need to stray too far, some of your most recognisable garden birds this winter might be from much further away than you think! So, as you watch your birds for this year’s Irish Garden Bird Survey, it’s worth considering where they were before now, and where they might be when they’re not in your garden.

The Irish Garden Bird Survey is kindly sponsored by Ballymaloe. Click below to learn about taking part this winter.

The Real Homebirds

Many of our small garden bird species don’t venture far from where they hatched as a chick. When they become independent from their parents, they’ll do a bit of wandering (‘post-juvenile dispersal’) around the countryside, but even then, more than 90% generally stick within a 20km radius of where they hatched. Some of our most sedentary species that follow this pattern including the likes of Blue Tit, Great Tit and Coal Tit, as well as Dunnock, Wren and Robin. As they become adults and claim a territory, that radius tightens and they’ll rarely venture beyond 5km throughout the year, and often will be found within 1-2km where there’s enough suitable habitat. Needless to say, if the small birds aren’t moving far then the birds that eat the small birds don’t have to venture very far either! Though there are some interesting Sparrowhawk movements on record (i.e. ringed birds with known movements)– e.g. a Sparrowhawk moving from Wexford to Cork, another from Mayo to Clare, and some birds seemingly coming into Ireland from the UK in winter, your local Sparrowhawk is exactly that – local!

Some of our bigger birds take the same sedentary approach, with no real need to move beyond a pretty limited radius throughout their lives. If you’ve fledged in an area that meets all of your ecological needs in terms of regular food supply and suitable nesting space in summer, then there’s no sense in flying halfway across the country or migrating. For the likes of all of our crow and pigeon species it’s the same story, though that maximum radius might extend to 30-50km for some, and there are a handful of records of birds crossing the Irish Sea for Jackdaw, Collared Dove and some others.

In winter, Rooks form large communal roosts where they exchange information and benefit from the shared heat of a large group, but your nearest roost might be up to 20km away. The Rook in your garden today might have a decent commute to make this evening – bear that in mind when it’s spilling your sunflower seeds out of the feeder and wrestling your fatball feeders to the ground!

Coming from Near and Far

The picture is a bit more complicated for some other species, however. In the case of most of our thrushes and finches, the birds in and around your garden in the summer (the Irish breeding population) are mostly here in winter too. But the reverse isn’t always true, and a bird in your garden this winter might be from much further away than you think! See below for some interesting examples of birds that have moved between Ireland and other countries.

Note this data is the result of a huge amount of volunteer and professional bird ringing, which is coordinated and organised in Ireland by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), under the auspices of the British and Irish ringing scheme. The BTO have very kindly provided us with some Irish-specific data for the maps below, but if this topic interests you then check out the BTO website here for more facts and figures of birds ringed in Ireland that have either made long-distance movements or have lived quite a long time!

Locations where Goldfinches from the Republic of Ireland have been recorded, via the BTO.

Goldfinch

In some parts of their range Goldfinch are migratory. Our breeding population stays here all year for the most part, though will move around more in winter and form large feeding flocks that rove widely across the countryside. Some of the Goldfinches from the Irish-breeding population will move further though, including crossing the Irish Sea, and you’ll see from the map above that there’s even some movement to and from mainland Europe! In many cases this is juvenile dispersal – i.e. juveniles travel further than adults, to explore the world and find good feeding areas. Conversely though, some of the Goldfinches that either bred or hatched in the UK in the summer seemingly move to Ireland for the winter too. So, the Goldfinches in your garden could be local birds but in all likelihood, the more you have then the more likely some of them are from much further away in Ireland, and possibly the UK too!

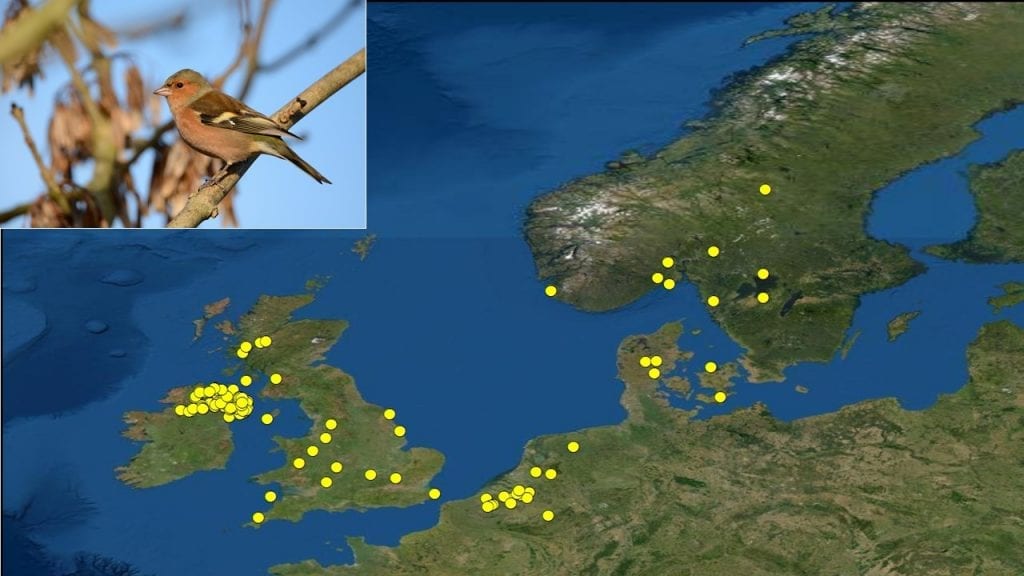

Locations where Chaffinches from the Republic of Ireland have been recorded, via the BTO.

Chaffinch

Staying in the finch family, while none of us ever tire of seeing Goldfinches, we tend to take Chaffinches for granted a bit. The males can have some nice autumnal reds, but the females are a very plain brown, and while Goldfinches have delighted everyone with their increases in recent decades, there have always been pretty decent numbers of Chaffinch around. So, are Chaffinches a bit boring by comparison? Well if you were impressed by the movements of our Goldfinches, then Chaffinches kick it up a gear!

Chaffinches from the coldest parts of northern Europe migrate south and west for the winter. When you think about how cold countries like Sweden, Norway and Denmark, as well as others like Lithuania and Germany get, coupled with heavy snowfall and short winter days, species like Chaffinch have to seek warmer climes to ensure they survive to the next breeding season! So, some of those ‘boring’ Chaffinches have traveled quite a long way to spend the winter in Ireland. Some will have come via the North Sea and Scotland, whereas others probable funneled south down through Denmark and then headed west through the Netherlands, into the UK and eventually ending up hoovering up the bits of peanut and sunflower seeds underneath your birdfeeders!

Chaffinches scientific name Fringilla coelebs translates from the Latin to ‘small bachelor bird’, because the scientist who named it saw mostly males in his Swedish homeland over the winter. A higher proportion of females migrate from these areas, with the males presumably having half an eye on next spring and getting back to the breeding grounds quickly to claim a territory!

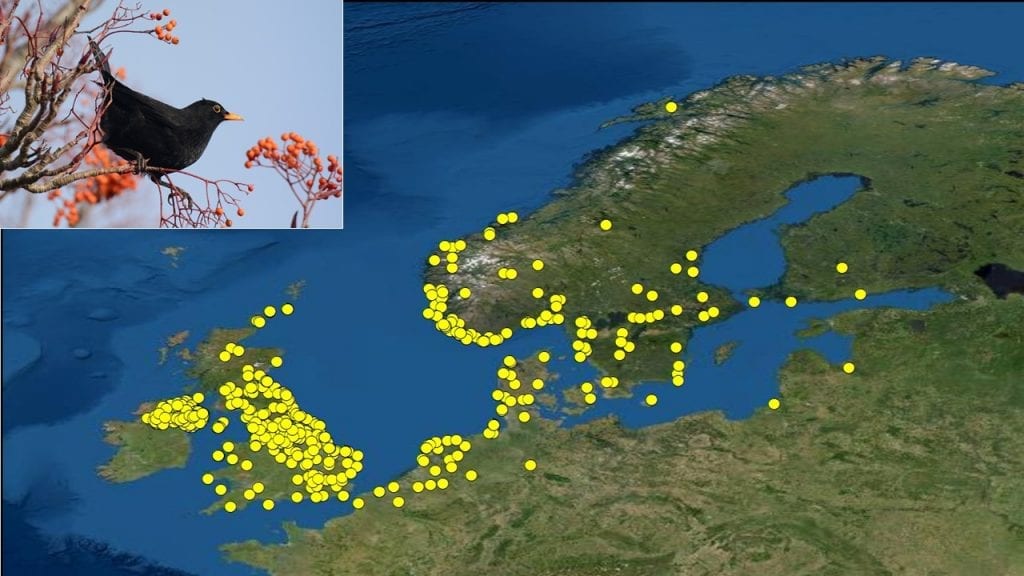

Locations where Blackbirds from the Republic of Ireland have been recorded, via the BTO.

Blackbird

This is one of the few bird species that everyone in the country could comfortably identify, and as with Chaffinch above there’s a risk of taking them for granted as a bit boring. Blackbirds tend to be in the top 3 garden birds every winter in Ireland, and that’s partly due to the influx of hundreds of thousands, probably into the millions, that come here from all over northern Europe to spend the winter. In October and November you might open your curtains to see 3 or 4 Blackbirds meticulously stripping a hedge or tree of it’s ripened berries. There’s a good chance these are birds that have arrived in Ireland overnight from Finland, Scandinavia, the Baltic States, Germany, or maybe the Netherlands or Belgium.

One Blackbird ringed near Kalingrad in Russia (yes, Russia!) in April 1971 was found dead over 5 years later in Donegal – a distance of 1,797km! Honourable mention goes to a Finnish Blackbird, ringed as a nestling in 1970, found dead in Kerry the following February – a distance of 2,271km by a Blackbird that wasn’t even a year old! So when you’re filling your feeders with sunflower hearts, nyjer and peanuts, don’t forget some chopped up apples and pears for the Blackbirds – some of them have a big return journey ahead of them in the spring! We also get a smaller influx of Song Thrushes and Mistle Thrushes from some of these countries each winter, including Scotland too.

Locations where Starlings from the Republic of Ireland have been recorded, via the BTO.

Starling

The star of the show though is the Starling! This is a species that is declining across most of Europe, though the Irish population is doing okay. Starlings famously form huge flocks, often with 10’s of thousands of individuals, that dance across the sky in what are known as ‘murmurations’, before flying into the nearest reedbed or group of trees to roost for the night. These aren’t just the birds that nested across Ireland this past summer though, these flocks consist of birds from all over northern Europe – even further afield than either Chaffinch or Blackbird above. I’m talking Russia, Finland, Scandinavia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, as well as Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands. That noisy pair that nested under your roof tiles are in there too somewhere! If you find a Starling murmurations this winter, be sure to let us know!

Hopefully that has given you a newfound appreciation for some of the more common birds in your garden! Don’t forget the Irish Garden Bird Survey starts on Monday the 30th of November and is open to everyone to take part. The more gardens involved, the better we can monitor our garden birds!

The Irish Garden Bird Survey is coming up soon and taking part couldn’t be easier! Click here for full details about the survey as well as as advice on caring for your birds through the winter.

We are hugely grateful to Ballymaloe for their sponsorship and support of the Irish Garden Bird Survey.

Click below to download your count form for this year’s Irish Garden Bird Survey.