The Dalkey islands are lying relatively quiet these days, with ‘our’ Arctic Terns on migration to the wintering grounds.

Until recently, we didn’t truly understand the scale of the journey Arctic Terns undertake each season. At-sea-surveys and observations of ringed Arctic Terns (birds with individually coded rings attached to their legs) in the Southern Ocean, hinted that the Arctic Tern undertakes the longest migration of any species. However, there was no definitive proof, and if there is one thing scientists like, it’s hard evidence.

Arctic Tern with leg-flag inscribed ‘MV’. Originally ringed on the Skerries Islands in Wales, it was observed on Dalkey Island in 2020 and 2022. (Jan Rod).

Arctic Tern with leg-flag inscribed ‘MV’. Originally ringed on the Skerries Islands in Wales, it was observed on Dalkey Island in 2020 and 2022. (Jan Rod).

To gather this evidence though, scientists needed a way of tracking these birds across real time. Thankfully, in recent decades, tracking devices have become small enough to be fitted to birds as small as Arctic Terns, which on average weigh about 100 gm (about 4 AA batteries).

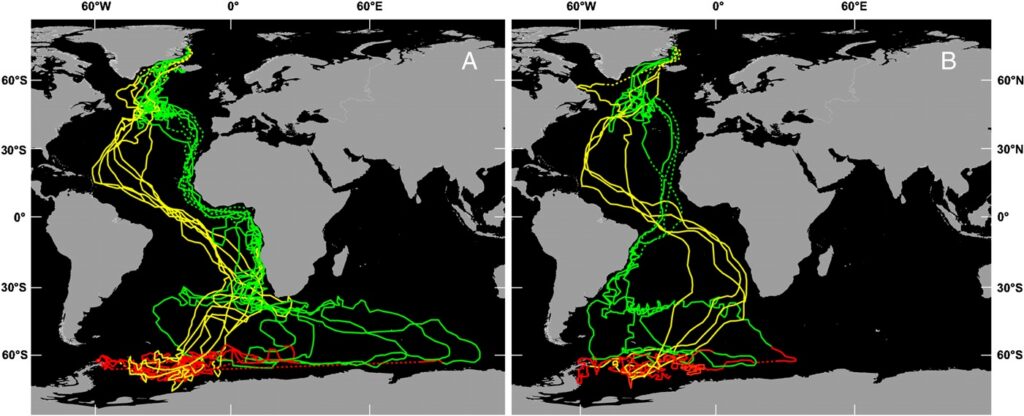

The first study published in 2010 tracked Arctic Terns from their breeding grounds in Greenland and Iceland. Their findings confirmed previous suspicions – that the main wintering area for Arctic Terns is around Antarctica, and that Arctic Terns do undertake the longest migration of any species on Earth (1).

Geolocator tracks from 11 Arctic Terns (10 from Greenland and 1 from Iceland). Image taken from Egevang et al. 2010. Full reference below.

Geolocator tracks from 11 Arctic Terns (10 from Greenland and 1 from Iceland). Image taken from Egevang et al. 2010. Full reference below.

Indeed, one of the Arctic Terns included in a later study undertaken at the Farne Islands in the UK, made a staggering 96,000 km round trip to and from the breeding grounds (2). Given these distances, over the course of their lives (up to 25-30 years), Arctic Terns will travel the equivalent distance of 3-4 round trips to the moon.

One of the reasons Arctic Terns migrate these distances is to chase the light. By moving from pole to pole, Arctic Terns essentially have summer conditions all year round, and the longer days summer brings. These longer days mean that Arctic Terns, which hunt by sight, can forage for longer periods of time.

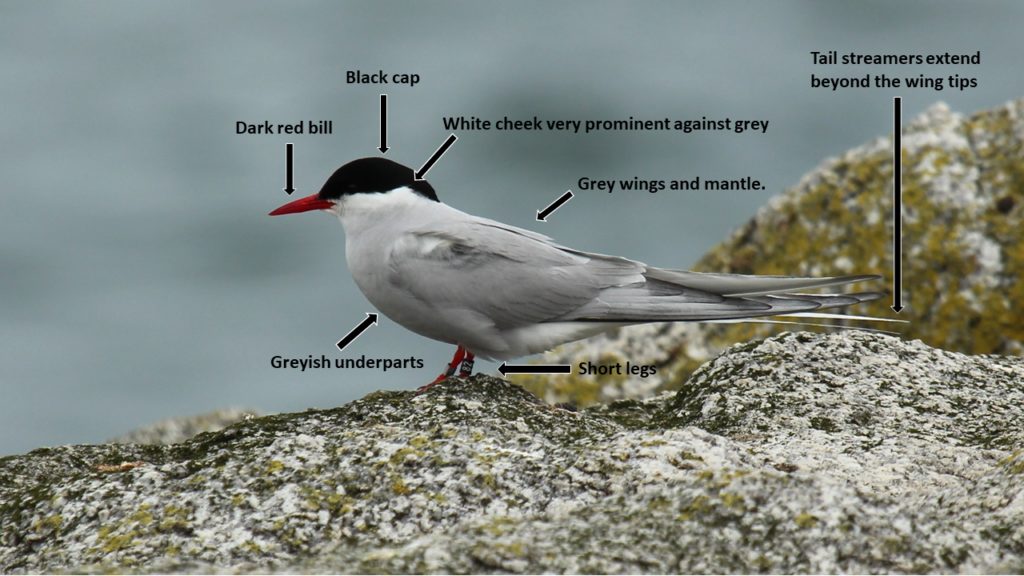

Arctic Terns have to contend with freezing temperatures. To minimise heat loss they have evolved short legs and bills compared to other tern species, to reduce the amount of surface area exposed to the elements. (Jan Rod).

Arctic Terns have to contend with freezing temperatures. To minimise heat loss they have evolved short legs and bills compared to other tern species, to reduce the amount of surface area exposed to the elements. (Jan Rod).

Many of the Arctic Terns included in tracking studies reached the Weddell Sea around Antarctica in November, so there is a distinct possibility that some of ‘our’ Dalkey terns will be arriving there shortly. And in just a few short months they’ll start making their way back to the breeding grounds, to hopefully raise another generation.

The Dalkey Tern Project is a partnership between BirdWatch Ireland and Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council.

References:

(1) Egevang, C., Stenhouse, I.J., Phillips, R.A., Petersen, A., Fox, J.W. and Silk, J.R.D. (2010). Tracking of Arctic terns Sterna paradisaea reveals longest animal migration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, [online] 107(5), pp.2078–2081. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0909493107.

(2) Redfern, C.P.F. and Bevan, R.M. (2019). Overland movement and migration phenology in relation to breeding of Arctic Terns Sterna paradisaea. Ibis. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12723.

Geolocator tracks from 11 Arctic Terns (10 from Greenland and 1 from Iceland). Image taken from Egevang et al. 2010. Full reference below.

Geolocator tracks from 11 Arctic Terns (10 from Greenland and 1 from Iceland). Image taken from Egevang et al. 2010. Full reference below. Arctic Terns have to contend with freezing temperatures. To minimise heat loss they have evolved short legs and bills compared to other tern species, to reduce the amount of surface area exposed to the elements. (Jan Rod).

Arctic Terns have to contend with freezing temperatures. To minimise heat loss they have evolved short legs and bills compared to other tern species, to reduce the amount of surface area exposed to the elements. (Jan Rod).