Guillemot

| Irish Name: | Foracha |

| Scientific name: | Uria aalge |

| Bird Family: | Auks |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

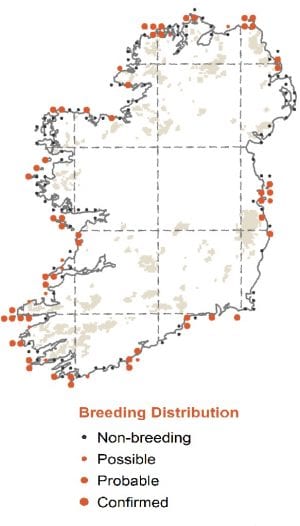

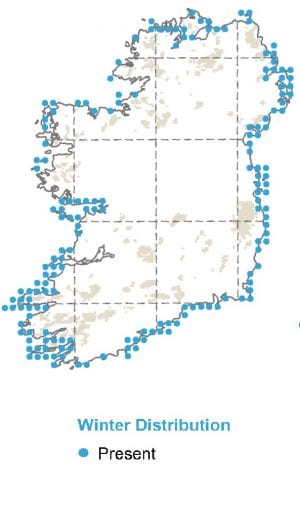

Resident, though occur inshore/ land during the breeding season, March/April to August/September.

Identification

The commonest species of Auk in Ireland, a highly marine species which are only found on land in the breeding season. A dark brown and white seabird, brown above and white below, with a distinct breeding plumage. In the breeding season head and neck completely dark brown, in the winter white on front of the neck and face. At a distance can be confused with Razorbill. Guillemot has a longer body, browner upperparts with less white on the side of the body and a lighter bill. Shows a darker 'armpit' than Razorbill. Seen flying in lines close to the sea with Razorbills.

Voice

Vocal in colonies with birds giving repeated nasal notes and prolonged bellowing. The young on the sea also give a high-pitched call after leaving the breeding colony.

Diet

Mainly small fish, some invertebrates, caught by surface diving.

Breeding

Comes ashore to nest from May onwards, colonies deserted by the first week in August. Nests on cliff ledges, often in large colonies, defends the smallest nest territory, sometimes only 5cm square. Restricted to cliffs with suitable ledges. Lays egg directly on to rock.

Wintering

Winters at sea. Some Irish birds are believed to winter near their breeding sites.

Monitored by

Breeding seabirds are monitored through seabird surveys carried out every 15-20 years.

Blog posts about this bird

Embracing our maritime heritage this National Heritage Week

National Heritage Week takes place from 17th-25th August 2024. National Heritage Week celebrates Ireland’s cultural, built and natural heritage, uniting communities, cultural institutions, academics and organisations to build awareness about the value of heritage and support its conservation.

By Rosalind Skillen

Over the years, National Heritage Week has grown to become an island-wide event celebrating all aspects of our built, natural and cultural heritage.

It may be surprising to learn that policy related to the marine environment and foreshore section sits in the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage – not the Department of Environment, Climate and Communications, as some may assume. This reflects the fact that, as an island nation, our history and heritage have been shaped by the sea and Irish rivers, lakes, and wetlands.

It is also one of the primary reasons why the nine day-long National Heritage Week now includes a Water Heritage Day, held in partnership with the Local Authority Waters Programme. Water Heritage Day is happening on Sunday 25th August 2024 and the day celebrates water throughout Ireland, its history, heritage and our connections with it. It also gives us the opportunity to reflect on the importance of water to our daily lives and consider what more we can do to conserve this valuable resource.

The theme of this year’s National Heritage Week is “Connections, Routes and Networks”, inviting us to explore the ways we are connected to each other through physical or cultural connections.

When we think about the relationship between these three strands – heritage, the sea, and connection – there are several dimensions to this relationship. The sea connects us to the natural world. It also connects people, places, cultures and economies. It is a site of trade and transportation, an issue of mutual benefit and cooperation, and a home for many diverse ecosystems that are bound together in a complex web of ecological interdependence.

Take the Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of Ireland. To take the 2024 theme of “Connections, Routes and Networks”, the waters in the Atlantic transported millions of Irish emigrants to the New World in one of the most tragic periods of Ireland’s history. Where sea meets shore, the Atlantic is renowned for its stunning and rugged coastline, its deep maritime heritage, strong history of fishing, and its variable and windy weather. This is one of the most important coastlines for seabirds, with Galway Bay and surrounding islands hosting some of the largest aggregations of Kittiwake, an internationally important breeding population of Guillemot, as well as important colonies for Puffin, Razorbill and Fulmar. Further north in Mayo, the coastline contains breeding sites for Terns, Auks and Fulmar.

Covering 1/5 of the Earth’s surface, the Atlantic is not only part of Irish heritage but is also a connector. The Atlantic not only connects two continents and serves as a network for global trade, but it also is a route used by seabirds from the UK, Ireland and the US. Seabirds from all 3 nations use the Atlantic as a migration route for breeding and feeding, and there is data showing that US and Irish birds use one of our most important MPAs (NACES) nestled in the heart of the North Atlantic Ocean. In 2021, OSPAR designated NACES as an MPA following research led by BirdLife International, which used tracking data from 21 species of seabirds across 56 colonies. This tracking data revealed that 5 million birds, including Puffins that breed on Skellig Michael, use the NACES MPA every year, making the site a seabird hotspot. A “connector” in the truest sense, the site is one of the most significant congregations of migratory seabirds in the Atlantic.

Conclusion

As the summer draws to a close, with many looking forward to a new routine or the return of school, National Heritage Week offers an opportunity to look back and to appreciate our coasts, seaports and vast maritime area.

Crucially, protecting the marine environment will be vital to preserving our rich Irish heritage for future generations. At the time of writing, we are still waiting for the publication of national Marine Protected Area (MPA) Bill, a vital piece of legislation that would see 30% of Ireland’s water designated as MPAs by 2030, including 10% strictly protected. The MPA Bill was promised in the Programme for Government (2020), and multiple Government announcements and speeches thereafter. We need robust marine protection and effective management of Irish waters to protect the rich maritime heritage that we enjoy across Ireland, and to preserve it for more generations to come.

Find out more about Fair Seas campaign to protect 30% Irish seas by 2030:

FairSeas | Building a Movement of Ocean Stewardship

Find out more about events taking place during National Heritage Week:

Home | National Heritage Week 17th – 25th August 2024

Victims of east coast oil spill are a stark reminder of the urgent need to plan ahead

In the first week of May, our already busy phone lines grew busier as reports of bird casualties came in from all along the east coast: Newcastle. Kilcoole. Carnsore Point.

There had been an oil spill. It was an event that we and many other organisations hoped would never happen, though one we had anticipated and tried to prepare for as much as we possibly could.

Leading the response, Kildare Wildlife Rescue (KWR) set up a network comprising their own staff and volunteers, National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) rangers, trained Oiled Wildlife Response Network (OWRN) responders, BirdWatch Ireland staff, Seal Rescue Ireland and others to ensure that as many birds as possible could be located, rescued and brought for rehabilitation.

Feathers provide birds with waterproofing that protects them from cold water reaching their skin. Even a small amount of oil can damage the structure of the feathers, compromising their waterproof quality and leaving a bird at risk of hypothermia and a rapid deterioration in body condition.

Oiled Guillemot on Wicklow Beach. Photo: BirdWatch Ireland.

Acutely aware of these dangers, we knew we had to act fast. Finding the birds wasn’t a problem, as reports of oiled birds, primarily Guillemots, came flooding in from both responders and the public. However, catching them was a slightly trickier task that required great skill, patience and care. Rescuers had to take care not to spook the birds and drive them back into the water. Guarding their own safety was also crucial, with all responders suiting up in PPE to protect themselves from the likely carcinogenic substance. Approximately 140 birds were retrieved, but this represents only a fraction of the birds affected, as it’s likely that many multiples of that number perished far offshore, never to be found. Those that were rescued may have been the so-called “lucky ones”, but they still had an extremely trying journey ahead. The rehabilitation process is both lengthy and complex, with each bird having to pass a number of veterinary examinations before it can go through the washing process. The washing procedure can last up to 45-minutes and is quite a stressful experience for a bird so it is crucial that they are in good condition before it begins. Once the washing process was complete, each bird remained in care at KWR, where they were closely monitored until they were deemed fit for release.

Oiled Guillemot at Kildare Wildlife Rescue. Photo: Kildare Wildlife Rescue.

Several of these birds were successfully released at a beach in County Wicklow recently, three weeks after they were rescued. Many others will surely follow but sadly, there will be others too weak to withstand this anthropogenic disaster. As a member of the Oiled Wildlife Response Network (OWRN), BirdWatch Ireland has been calling for the establishment of a formal national oiled wildlife response plan for many years. No words can convey the urgency of this better than the distressing images of oil-slicked seabirds fighting for their lives on Ireland’s beaches. The recent spill should serve as a warning signal for our leaders. It’s not a matter of if, but when, another similar disaster will occur and we need to do all we can to ensure we’re ready.