Razorbill

| Irish Name: | Crosán |

| Scientific name: | Alca torda |

| Bird Family: | Auks |

red

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

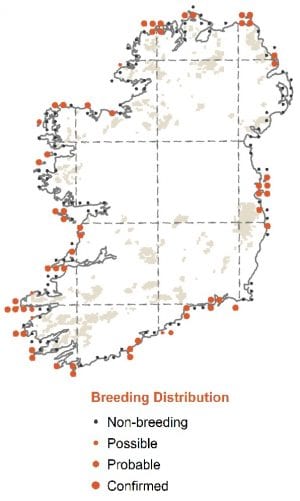

Resident, though occur inshore/ land during the breeding season, March/April to August/September

Identification

A species of Auk, highly marine and only found on land in the breeding season. A black and white seabird, black above and white below, with a distinct breeding plumage. Head and neck all black in the breeding season with white on the front of the neck and face in the winter. Bill heavy, except in first winter birds. At a distance can be confused with Guillemot. Razorbill slightly smaller with blackish rather than brownish upperparts, more white on the side of the body and the bill distinctly heavier and blunter on adult birds. White 'armpit' compared to the darker 'armpit' of the Guillemot. Seen flying in lines close to the sea with Guillemots.

Voice

Similar to Guillemot but tone is harder.

Diet

Mainly small fish, some invertebrates, caught by surface diving.

Breeding

Nests on sea cliffs. Similar in habits to Guillemot with which it will breed in mixed colonies. Returns to colonies in March and April and departs by August. Will also use more secluded nest sites, fissures in the cliffs and also in screes, where it is more difficult to see, except when birds stand outside of their nest sites.

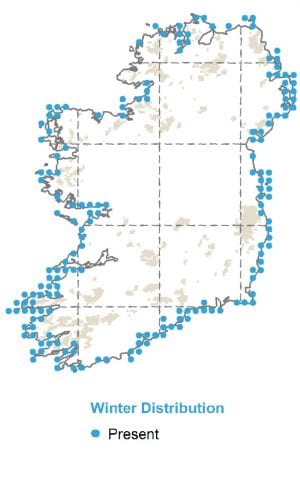

Wintering

Winters at sea.

Monitored by

Breeding seabirds are monitored through seabird surveys carried out every 15-20 years.

Blog posts about this bird

Too Close for Comfort - BirdWatch Ireland remind everyone not to photograph bird nests this summer

Looking at a bird nest in close quarters risks disturbing the parents, causing chicks to prematurely leave the nest, and increases the risk of a predator finding a nest.

It’s always an exciting moment when you realise you have birds nesting in your garden, or when you’re out for a walk and spot a bird dashing into a hedge with nest material or food for their young. Of course, bird nests are quite mysterious, with their often-hidden locations and intricate designs, and the prospect of watching the progress from nest to eggs to chicks to fledglings is a tantalising one – a rare glimpse into an important part of the lifecycle of your favourite species. Similarly, thousands of people look forward to the Swallows returning to their sheds year after year, and hopefully rearing multiple successful broods before their return trip to Africa. Unfortunately, though, by looking into that nest, or trying to get some photos to share with family, friends and social media, you could be putting the nesting attempt at risk of failure. And nobody wants to do that! So please, resists the temptation to peek into any nests this summer, but rather watch the adults coming and going from a safe distance, and keep your eye out for healthy fledglings a few weeks later!

A lot of people don’t realise that it’s actually illegal to disturb and/or photograph nesting birds, without a specific licence from the National Parks and Wildlife Service. “Under Section 22 (9)(f) of the Wildlife Act, 1976 (as amended) a licence is required for a person to take… video/pictures of a wild bird of a species… on or near a nest containing eggs or unflown young”. This is a good law and is in place with the best interests of the birds in mind.

Please don't go near nesting birds, eggs or chicks - wait for them to fledge and there'll be loads of opportunities to see them!

So, what are the risks? Well first of all, the adults will likely leave the nest as you approach. This means that eggs that need to be incubated, or chicks that need to be kept warm, are exposed and will rapidly lose heat, putting them at risk. If the chicks are more than half-grown, you might find the adult isn’t on the nest as you approach, but your presence will prevent them from feeding their chicks – and those chicks need a lot of food every day if they’re going to fledge successfully! As chicks in the nest get older, there’s a risk that you will cause them to ‘explode’ from the nest. The chicks see you as a predator, so when you approach the nest they think their time is up – so they take a risk and jump from the nest, in the hopes of escaping. By causing them to fledge too early, you’re greatly decreasing their odds of survival. It’s important to remember that birds see humans as predators, so they act accordingly by trying to escape from the predator. In the natural world, there’s nothing good about a large animal trying to seek out your nest – it can only be a bad thing!

In some cases, you might approach a nest and the parent bird stays sitting on it. A lot of people take this as a good sign that no disturbance has been caused and that the bird is content with your presence, but that’s not the case! There are studies that show that birds who remain on the nest like this have greatly elevated heart rates for several hours afterwards. So, they were very stressed as you approached, but they were hoping that by not moving they wouldn’t give away the location of their nest.

A Swallow gathering nest material.

Lastly, even if you’re in and out quickly – no chicks jump the nest, and the adults return quickly, there can still be disastrous consequences. By approaching a nest, you can give away it’s location to potential predators – cats, Magpies, foxes, dogs, etc. – will either have seen you check the nest and think, “I wonder what they were looking at?” and remember to do their own investigation later, or by approaching the nest you might leave a trail of flattened grass or move branches or briars out of the way, all tipping off potential nest predators too.

So, without wanting to fearmonger, you can potentially put birds and their eggs/chicks in jeopardy by poking your head in to have a look or try and get a photo. But you’ll put them at no risk by observing them come and go from several metres away, and you’ll hopefully have some fledgling chicks to look forward to seeing in a few weeks’ time. So why risk it?!

Nestbox cameras provide the best of both worlds and are perfectly safe and legal if they’re installed early in the year before the birds starting nesting in them. Nests should only be ‘inspected’ by people with the right training and licensing, who are gathering scientific data to advance our understanding of the species in question, with a view to improving conservation efforts.

A nestbox camera, that you've installed before the breeding season starts, is a great way to monitor your nesting birds without causing them any disturbance.

If you happen accidentally to disturb a nest, the best thing to do is to leave the site immediately. If the chicks jump, and you can safely return them to the nest, then try to do so, but if that’s not possible, putting them somewhere close by in a tree or hedge is the best thing to do. They stand a much better chance of survival if their parents look after them than if they have to be taken into human care. In extreme cases, contact the Irish Wildlife Hospital (http://wildlifehospital.ie/) for advice, but try the above steps first. It’s better to leave them be and watch from a distance to see if the adults return to them than to put them in a box first and ask questions later.

If you see a fledgling on the ground, don't pick it up - watch for an hour or more to see if the adults are tending to it. If they are, leave it be.

So, regardless of the law, and no matter how careful you are, it’s really down to ethics and the birds’ welfare being paramount. For this reason, we don’t ‘like’ or share any photos sent to us of birds’ nests or chicks. Even if your photo was taken from 20 metres away with the longest lens money can buy and no disturbance was caused, we feel it’s best not to share these as it may encourage others (who haven’t read this article!) to go get their own photos of their nesting Robins or Swallows, and so the knock-on effects simply aren’t worth it.

Play it safe at Seabird Colonies

Arguably the greatest example of this sort of issue is in seabird colonies, such as Great Saltee in Wexford, Ireland’s Eye in Dublin, and others. These islands are easily accessible and provide a fantastic opportunity to see large numbers of amazing seabirds coming and going during the breeding season. Indeed, those of us lucky enough to have done so can probably still remember the first time we saw a Puffin or the sights and smells as we approached a large Gannet colony. Allowing visitors to access these islands is undoubtedly a good thing as it engages people with seabirds, birds and conservation. It makes them care about wildlife, and we need more of that!Unfortunately, most people don’t realise when they’re causing disturbance in these colonies, and what can look like a fantastic photo of a Gannet, Puffin, Shag or Guillemot might actually be illustrating a bird that is very stressed and in fear for its egg or chick. As above, there’s research on seabirds that show that they have elevated heart rates and stress levels for hours after a human has approached their nest, even though they didn’t fly off and, on the surface, might appear to have been happy to tolerate the human. So, just because a bird is sat on its nest as you approach doesn’t mean that it’s happy for you to do so. Really what they’re thinking is that they’ve put months of work into getting to this stage of nesting, and they don’t want to give that up unless they absolutely have to. Remember, as far as that bird knows you’re a predator!

People frequently get much too close to nesting birds at seabird colonies around the Irish coast.

People frequently get much too close to nesting birds at seabird colonies around the Irish coast.

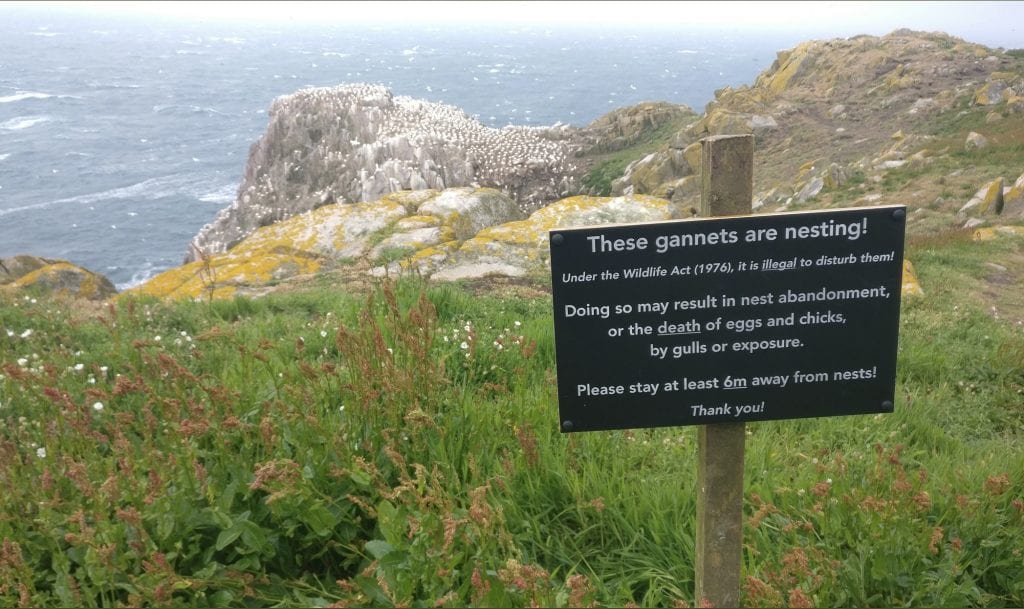

A recent study by Debs Allbrook of UCC found that Gannets nesting on the edge of the main colony on Great Saltee were disturbed the most and had the lowest nest success rate. She also found that it was photographers who ventured the closest (2.6m on average). Many photographers go out to the Saltees armed with huge lenses with eye-watering zoom capabilities, and yet the evidence still shows that this doesn’t result in them sitting further back to get these photos – many still go much closer than they should. The resulting disturbance lead to nest predation by gulls and a waste of months of effort on the part of the Gannets. That wasn’t the gulls’ fault, it was the humans’! Thankfully, Debs’ research also involved the installation of a sign near the Gannet colony, informing visitors to maintain a distance of at least 6m from the nesting birds, and this seems to have improved the behaviour of photographers and other visitors, and resulted in less disturbance as a result. (Note: this distance is suitable for this species and this location but is not a universal constant for all seabirds and all colonies, so learn to read the signs of disturbance and behavioural disruption.)

Debs recently summarised her important research in our Wings membership magazine (Summer 2021 issue) and we've that article free to view for non-members too, by clicking this link.

The full peer-reviewed study in the Journal for Nature Conservation can be read by clicking here.

A sign has been erected on Great Saltee, based on Debs Allbrook's research, to encourage best behaviour near the nesting Gannets.

Puffins nest in burrows, and after a couple of hours at sea gathering sandeels and sprat they want to fly straight back to their burrow and feed their chicks immediately. If you’re finding that a Puffin is walking around near you, sandeels in bill, seemingly not bothered as it poses for photo after photo, then it’s likely that you’re the reason it’s not returning to its burrow. Basically, if you’re finding it relatively easy to get photos of seabirds, then consider that it might be a bit too easy and you might be unintentionally disturbing the bird in a way that isn’t immediately obvious to you.

All of the above goes for the other seabirds too – Guillemots and Razorbills on the cliffs, Shags nesting between or under boulders, and even gulls nesting on flat and grassy areas of these islands. Gull chicks will run away at the sight of people, and this often results in them running off the side of a cliff, or running towards the nest of another gull, who will attack the intruder.

Learn to spot the signs of disturbance, which can vary between adults flying away from the nest, to a parent bird sitting tight but becoming agitated.

It’s true that seabirds on islands that regularly get visitors can become more habituated to human presence than islands where people never visit, but this still requires a certain minimum distance to be maintained. And many photographers go out to these islands every summer, maintain a healthy distance from birds and their nests, and still come away with stunning photographs! So, don’t be discouraged – just be aware! Learn to spot the signs that your presence is stopping a nesting bird from going about its business as it normally would. It’s inevitable to accidentally ‘flush’ (cause to fly away) a bird when you’re walking around a seabird island or to cause a bird with a food delivery to circle the nest site rather than land, but the important thing is to take these as signs to retreat and ensure the bird can get back to its nest site as soon as possible. Don’t kick yourself when this does happen but use it as an educational moment and vow to avoid making the same mistake twice.

So, here are the key points:

- Don’t seek out nests or photograph them. Just because no harm is intended, doesn’t mean harm isn’t caused.

- You can get a license to photograph a nesting bird from the NPWS, but this doesn’t confer on you the right to disturb the birds in the process.

- Nest visits should only be carried out by people who are trained and licensed to minimise the risk, and in order to gather scientific data that is important to the monitoring and study of the species in question.

- Take the chance to enjoy the birds around you, visit a seabird colony this summer, and take lots of photos, but be sure to keep your distance from the birds and their nests!

Some below for some interesting articles on this topic from other websites and organisations:

Do’s and Don’ts of Nest Photograph (Audobon Society)

Unwitting Tourists Cause Gannet Nests to Fail on Saltee (UCC)

Birding Ethics & Practical Guidelines (incl. Photography) (WorldBirds)

BirdWatch Ireland staff meet ministers to demand action over shocking wild bird declines

On World Curlew Day, the Curlew is a symbol of successive government failure to protect our wildlife.

BirdWatch Ireland’s top scientists are today, on World Curlew Day, meeting Ministers of State Malcolm Noonan and Pippa Hackett to discuss alarming wild bird declines. Experts on farmland birds, waterbirds and seabirds will tell the ministers that successive governments have ignored biodiversity and that they must seize the moment to turn around the fate of so many species.

Last week BirdWatch Ireland and RSPB Northern Ireland jointly published the Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 list. Using a traffic-light system, it reviewed the conservation status of 211 regularly occurring bird species in Ireland. The findings revealed a shocking 46% increase in the number of bird species on the Red List, the highest threat category, since the last review in 2013. Altogether 63% of bird species on the island of Ireland are now in serious trouble, a truly shameful and unacceptable situation that must urgently be addressed by government.

Ministers will hear that the catastrophic declines of farmland birds, especially breeding waders like the Curlew and the Lapwing, are a consequence of successive agriculture and forestry policies which have prioritised intensification and afforestation at the cost of homes for biodiversity.

Dr. Anita Donaghy, BirdWatch Ireland Head of Species and Land Management said:

“On World Curlew Day we are still waiting on government to implement the recommendations of the Curlew Task Force published in 2019. We cannot delay anymore.

“We have reached a tipping point in the future of many of our wild bird populations. The declines in the Kestrel, the beautiful and formerly common farmland bird of prey that hovers while hunting rodents, are grave. They indicate that our countryside is becoming ever more inhospitable for nature. This must be resolved in AgriFood Strategy 2030, the CAP Strategic plan and in the Forestry Programme for once and for all.

“Successive governments have targeted funding on intensification and forestry premia, and much less so at supporting farmers to save the habitats of threatened species on their farms.”

Dr. Lesley Lewis of BirdWatch Ireland, co-author of the Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland paper said:

“Ireland’s waterbirds are declining at rate higher than those in most other EU member states. Government must now put in place a multilateral and all-of-government approach with biodiversity at the heart of decision making. Otherwise the trend will be for more species to join the Red List and to head for extinction here”

Dr. Stephen Newton, BirdWatch Ireland Senior Seabird Conservation Officer said:

“Post Brexit, Ireland is the most important EU member state for the 4 Red-listed seabird species Puffin, Razorbill, Kittiwake, and Leach’s Storm Petrel. We must meet national and EU targets to cut emissions and also ensure that offshore renewables safeguard threatened species. To do this we need a lot more funding for research into species ecology”.

Oonagh Duggan, BirdWatch Ireland’s Head of Advocacy said:

“Failure to adequately fund the National Parks and Wildlife Service has hindered species and habitat conservation at every level. Government ambitions to meet climate targets can be supported by ambitious restoration of habitats, but significantly increased staff numbers and funding is required within the NPWS so it can be fit for purpose for this task."

People frequently get much too close to nesting birds at seabird colonies around the Irish coast.

People frequently get much too close to nesting birds at seabird colonies around the Irish coast.