Rook

| Irish Name: | Rúcach |

| Scientific name: | Corvus frugilegus |

| Bird Family: | Crows |

green

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

Resident. One of Ireland's Top 20 most widespread garden birds.

Identification

A species of crow. All crows have sturdy legs and strong bills and are intelligent and social in nature. The Rook is a familiar bird, which nests in colonies in tree tops called rookeries. About the size of a Hooded Crow, the rook is all black and in certain lights can show a reddish or purple sheen to its plumage. Told apart from other species of crow by its 'trousers' the dropping feathers on its belly and the bare skin around its bill base on the adult birds. Juveniles lack this feature, which only develops in the spring of its second year, and then they can be difficult to separate from Carrion Crows (a rare breeder in Ireland); best told apart by the more peaked crown of the Rook. Often forages in the company of other crow species, especially Jackdaws. When separating Hooded Crows and Rooks in flight, Rooks has faster and deeper wingbeats, which makes it look like they are making more effort than the Hooded Crow.

Voice

A hoarse croaking call. When given in the colony can be very loud.

Diet

Feeds mainly on invertebrates. Food also includes small vertebrates, carrion, plant material and scrapes of all kinds. Found feeding in agricultural areas on pastures, fallows, occasionally in trees. Also found in town and cities feeding on refuse and food scraps.

Breeding

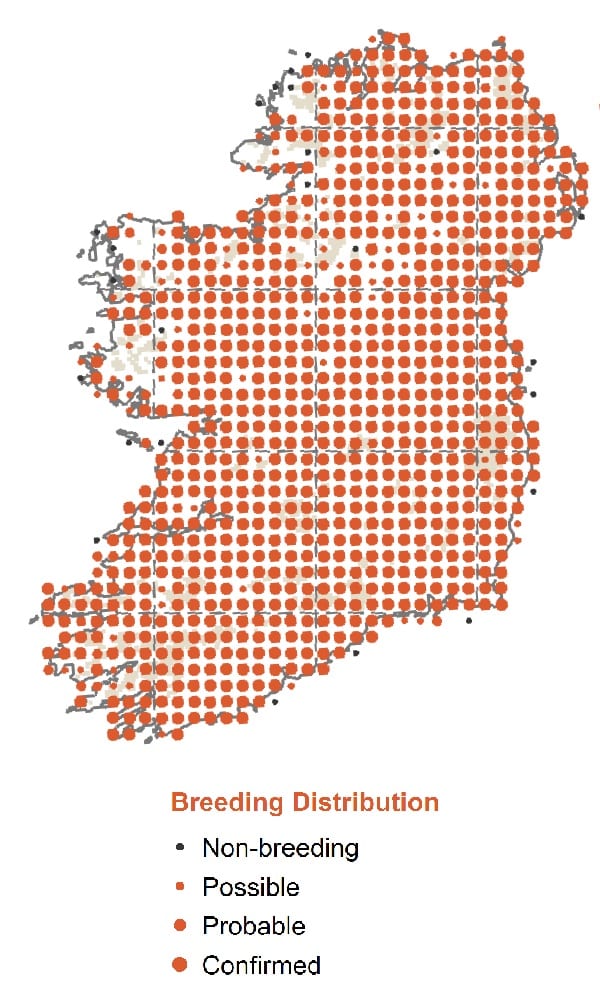

Builds a untidy nest in the tops of trees, usually quite high up, but not always can be quite close to the ground if the trees are short. In the late winter rookeries are a hive of activity as birds get ready for the coming breeding season. The species is widespread and abundant in Ireland breeding in all areas, it is only absent from the centre of towns and uplands areas. Rare or absent in parts of the west coast.

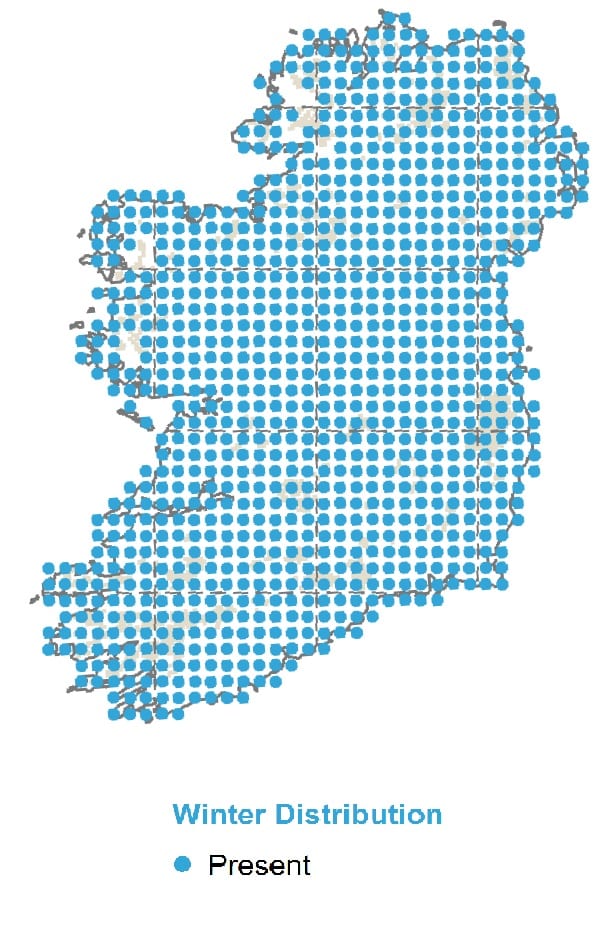

Wintering

Widespread in the winter when it forms large flocks, often with Jackdaws.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

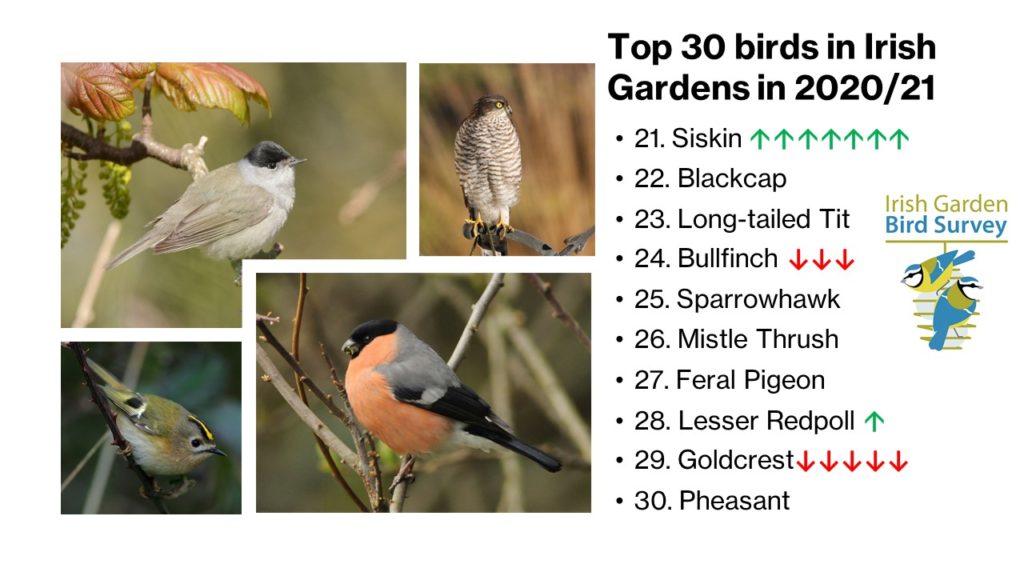

'Last Christmas' - Birds in Irish Gardens last winter

There's still time to take part in the Irish Garden Bird Survey!! See here for more details.

If you’re a BirdWatch Ireland member you’ll have already read the results of last year’s survey in your winter edition of Wings magazine. If you’re not a member, please join and support our work! But you can catch up on last year’s Irish Garden Bird Survey results with the overview below. If this is your first year to take part in the survey, don’t worry about knowing every single species that might appear in your garden – just familiarise yourself with the most common ones to start off. If you’re a survey veteran, then see how your garden bird list compares to the national average!

If you’re a BirdWatch Ireland member you’ll have already read the results of last year’s survey in your winter edition of Wings magazine. If you’re not a member, please join and support our work! But you can catch up on last year’s Irish Garden Bird Survey results with the overview below. If this is your first year to take part in the survey, don’t worry about knowing every single species that might appear in your garden – just familiarise yourself with the most common ones to start off. If you’re a survey veteran, then see how your garden bird list compares to the national average!

Over 90% of Irish Gardens

The species at the top of the list didn’t change much from previous years. Robin, as per usual, was on top, followed by Blackbird and Blue Tit. Great Tit and Magpie moved up a place each into 4th and 5th, thanks to a fall in the numbers of Chaffinch reported. Robins can still be territorial in the winter, so are pretty evenly spread across the country, while our Blackbird population is topped up by hundreds of thousands of migrants from Scandinavia in the winter, hence their high-ranking each year. Blue Tits and Great Tits are pretty ubiquitous too, and Magpies are very effective at exploiting both urban and rural habitats.

80-90% of Irish Gardens

Chaffinch and Goldfinch fell two and three places to 6th and 10th respectively, since the previous winter, and those declines were greatest in urban and suburban gardens rather than rural ones. On the back of a great breeding season, Coal Tit moved up three places to 7th place. House Sparrows kept 8th position, and Starling made it into the top 10 garden birds for the first time in a decade!

50-80% of Irish Gardens

Wren dropped two places to 11th, while species such as Dunnock (12th), Rook (16th), Collared Dove (17th) all stayed in the same position as the previous winter. When a winter is pretty mild (the occasional storm excluded) we tend to see this stability in the rankings across many species. There was some slight movement for Woodpigeon (14th), Jackdaw (15th) and Hooded Crow (19th), all of which fell one place. The mild weather tends to mean these species aren’t forced to retreat to gardens for food as much as in other winters. Song Thrush increased by around 2% and jumped to places in the rankings to 13th. Pied Wagtail rose up two places to 18th and occurred in >7% more gardens than they did on average over the preceding five year period. Despite being very common in towns, cities and shopping centre carparks, they’re actually seen in twice as many rural gardens as urban or suburban ones. Greenfinch continue to suffer the devastating effects of trichomoniasis (make sure to clean your feeders regularly!) and reached a new low for the species in the survey – 20th place.

20-50% of Irish Gardens

While the above species occur in more than 50% of gardens, you’re in the minority if one of the below appears in your garden this winter: Siskin jumped up 7 places (8%) since the previous year. They usually start to appear in gardens from mid-January onwards, but they were making appearances from late November right through to March in most parts of the country last winter. No other species made such a big jump pup the table! One of the bigger losers was Goldcrest - down 5 places to 29th, a decrease of nearly 8%. It was a mild winter, and a good breeding season for most species in 2020, so the reason for this isn’t immediately obvious. Bullfinch dropped three places to 24th, but this might just be due to the mild winter and abundance of feeding options in the wider countryside, as they’re not a bird that visits feeders and so aren’t as associated with gardens as other finches. Other species in the 20-50% band include Blackcap, Long-tailed Tit, Sparrowhawk, Mistle Thrush and Feral Pigeon. Again, not species that tend to avail of bird feeders with any regularity, but species who know how to make a good living in a human-dominated landscape, be it rural, urban or suburban.Best of the rest

Despite being a non-native species, Pheasants tend to be seen in 15-20% of gardens each year, which is surprisingly high considering they don’t tend to breed well in the wild, so are reliant on being released by gun clubs every autumn. Buzzards moved two places up the rankings and are seen over 15% of gardens each winter. Herring Gulls were in 11% of gardens, Black-headed Gulls in 4%, and 1.3% of gardens had some sort of gull visiting but weren’t sure what species! Great Spotted Woodpeckers are one of the most recent additions to our bird community, and over 4% of gardens had one visiting their peanut feeders (it’s always peanut feeders!) last winter. They’re now breeding in almost every county in Ireland, so expect to see them charging up the rankings table in the coming years. Last year was a mast year for acorns, which meant Oak trees were providing a huge bounty for species such as Jays, and as a result they were seen in fewer gardens than usual (8%, down 1% from the average). This tends to happen every few years. Lastly, Redwing and Fieldfare, our two wintering thrush species, both dropped a bit, thanks again to the mild winter.

See below for the full Top 30 birds in Irish gardens last winter, and their various ups and downs since the previous year. Most gardens record between 10 and 25 species over the course of a winter. Whether you have more or less than that, we still need you do to the survey!

See below for the full Top 30 birds in Irish gardens last winter, and their various ups and downs since the previous year. Most gardens record between 10 and 25 species over the course of a winter. Whether you have more or less than that, we still need you do to the survey!

We are hugely grateful to Ballymaloe for their sponsorship and support of the Irish Garden Bird Survey.

For more details about the Irish Garden Bird Survey click here, or download the survey form below.

King of the Ring - Ireland's record-breaking birds

The British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) recently published the ‘2020 Ringing Report’, detailing all of the birds ringed in Ireland and Britain up to the end of last year. Included in this is an update to the ‘longevity list’, i.e. the individuals of each species which have lived the longest. This always makes for fascinating reading, to see what ringed individuals bucked the trend by outliving their counterparts. Some birds can live a lot longer than you might think! See below for more on the Irish record-breakers, including one bird that is the oldest of its species seen by our staff this summer.

A Shag ringed on Great Saltee in Wexford as a chick in 1977 subsequently washed up on the beach at Greystones in Wicklow in 2007, making it a whopping 29 years and 11 months old!

Dipper

Next time you see a Dipper, happily bobbing away on a rock in a stream near you, this might make you wonder how long it has been using that same rock! A Dipper ringed as a chick in April 2008 under a bridge in Laois was caught by the ringer again 8 years and 9 months later! We have our own distinct subspecies of Dipper in Ireland, so research into this species in Ireland is particularly valuable and important.

Click here to read the full longevity list up to the end of 2020, on the BTO website.

Ringing birds, by people who are appropriately trained and licensed, is a valuable way to learn about the lifespan of birds, their annual survival rates, migratory movements and dispersal, and how individuals use a certain area. All of these things vary by species, by location (e.g. Irish birds might do something different to English birds of the same species) and by time, and changes to weather patterns, loss of prey or food supplies, or destruction of habitat might cause these to change, which we can again measure through ringing. Ringing involves fitting a bird with a small lightweight metal and/or plastic ring with a unique code on it, so that specific individual is recognisable in the future and we know exactly where it has been in the past, and when it was in that place. There are around 100 bird ringers on the island of Ireland, and all sorts of species are ringed here, from Robins to Ravens, Blackbirds to Brent Geese, Coal Tits to Cuckoos, Siskins to Swifts, and everything in between. If you’re interested to find out more about ringing see this link on the BTO website, and we’ve also been running a regular feature in our BirdWatch Ireland membership magazine ‘Wings’ to highlight ringing projects currently running in Ireland, so check that out too!Irish birds on the Longevity List

Over the years, many birds either ringed in Ireland, or ringed elsewhere and found in Ireland, have taken pride of place on the ringing list. Some have fallen from the top spot over time, including a Manx Shearwater from the Copeland Islands in Northern Ireland, which was the oldest known living wild bird in the world when it was re-trapped by ringers in 2003, 50 years since being ringed as an adult, making it at least 55 years old when it was caught in 2003! You can read more about Manx Shearwater ringing on the Copeland Islands in this recent article from our Wings magazine here. See below for seven Irish birds currently ranked as the oldest of their species in Britain and Ireland, and we’ve got one to add to the list from our conservation work this summer….Greenland White-fronted Goose

A white-front ringed on the North Slob in Wexford in 1985, was shot in Iceland in 2004, making it 18 years and 10 months old! Shag

Shag

A Shag ringed on Great Saltee in Wexford as a chick in 1977 subsequently washed up on the beach at Greystones in Wicklow in 2007, making it a whopping 29 years and 11 months old!

Wood Sandpiper

The Wood Sandpiper is a scarce passage migrant in Ireland, meaning they move through on migration in the autumn. A Wood Sandpiper caught on the Shannon Estuary in Limerick in 1974 was subsequently caught by another ringer in Belgium, 922km away and almost 8 years later. Some species that aren’t particularly common in Britain and Ireland might have a larger maximum lifespan recorded through ringing schemes elsewhere, but the examples here are the oldest individuals in Britain and Ireland for each species!

Stock Dove

This increasingly-scarce pigeon species has a well-established breeding population on the Copeland Islands in Down. One bird caught in 1953 was found a mere 10km away on the mainland, 9 years and 2 months later!

Short-eared Owl

A Short-eared Owl, ringed as nestling in the Forest of Balloch in South Ayrshire in Scotland was unfortunately shot in Cork, at 6 years and 8 months of age. It was originally ringed in May 1956 and met it’s untimely death in January 1963.

Rook

Many people are a bit surprised that species such as Rooks are ringed and studied, but we can learn a lot about bird behaviour and environmental change by looking at our most common species. A Rook chick ringed in May 1982 in Castlewellan in Down was found dead 7km away. That mightn’t surprise you, as they can move around a bit and 7km isn’t too far as the Rook flies. The surprising bit though, is that it was exactly 22 years and 11 months since it was ringed!

And in 2021, a record-breaking Roseate Tern!

Ireland has the two largest Roseate Tern colonies in Europe, Rockabill in Dublin and Lady’s Island in Wexford, accounting for over 90% of Roseate Terns in north-west Europe. Ringing has been a really important tool for the conservation work by BirdWatch Ireland and the National Parks and Wildlife Service at both colonies, helping to monitor the progress of each bird as they grow as a chick, and when they return as an adult. Because such a large proportion of the Roseate Terns at both colonies are ringed, we have a really good insight into the average age of the population, and in most years we record a few birds in their late teens or early twenties. Not bad for something the size of a Blackbird, that migrates to and from West Africa every year! This summer, one of our Rockabill Wardens Alex Fink, spotted a Roseate Tern that had been ringed in July 1993, making it 28 years old and the oldest Roseate on record in this part of the world! The majority of breeding Roseate Terns are 3-7 years old, so this bird has done extremely well for itself, and depending on how successfully it has been breeding over the years, and how successful its offspring have been, it might even be a great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandparent!For more details on the oldest ringed birds in Britain and Ireland, see the BTO website here.

For more information about ringing projects in Ireland, see our regular ‘Ringing Tales’ feature in our Wings membership magazine. Click here to see about becoming a member.

If you find a bird with a ring and need help to report it and find where and when it came from, email us here with as many details as you can provide, particularly the code on the ring.

Shag

Shag