Snipe

| Irish Name: | Naoscach |

| Scientific name: | Gallinago gallinago |

| Bird Family: | Waders |

red

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

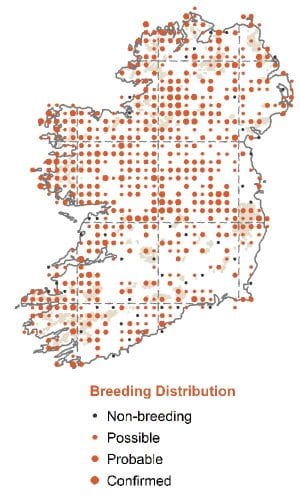

Summer visitor from west Europe and west Africa, winter visitor from Faeroe Islands, Iceland and northern Scotland.

Identification

A relatively common wader but not easily seen, unless flushed out of marshy vegetation, when it typically towers away in a frantic zig zag fashion. The disproportionately long, straight bill is easily visible in flight. If you are lucky enough to see one standing partially or wholly out in the open (usually at the edge of reeds), you will make out the series of dark brown, pale buff and black stripes and bars on the head and body - this produces a good camouflage effect.

Voice

Flight call an abrupt "scratch..". Song includes a far-carrying "chipper, chipper…" often at night - sometimes delivered from a fence post. During display flights over the nesting territory, they make an eerie goat bleating sound - this is called drumming and it is produced by stiff feathers sticking out at the tail sides, which vibrate as the bird flies in a roller coaster pattern in the sky.

Diet

Diet consists largely of vegetable matter and seeds, and earthworms, tipulid larvae and other soil invertebrate fauna.

Breeding

Nests on the ground, usually concealed in a grassy tussock, in or near wet or boggy terrain. Young leave the nest soon after hatching.

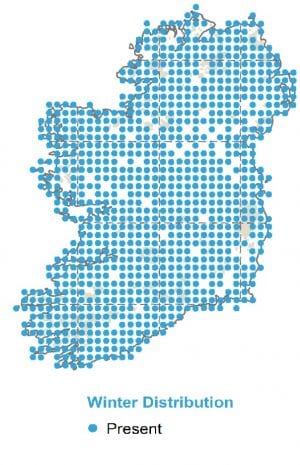

Wintering

Highly dispersed distribution in winter. They forage across a variety of wetland and damp habitats. Particularly high concentrations are found on the fringes of lowland lakes.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

BirdWatch Ireland presses parties to put People, Nature and Climate at the heart of election agendas

With potentially just weeks until a General Election, BirdWatch Ireland has written to political parties calling on them to put people, nature and climate front and centre.

In mid-October, we wrote to parties with a clear list of asks for nature, urging them to include them in their election manifestos and the next Programme for Government.

The letter acknowledges the many positive changes made in recent years, including the convening of the Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss, the financial support for the Breeding Wader EIP and support for the Nature Restoration Law, among others. However, while these steps are encouraging, we are urging our politicians not to lose sight of the ongoing twin biodiversity and climate crises in the years ahead.

Our bird populations are in a dire state, with 63% of species either Red or Amber-Listed Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland. Species once considered common and widespread such as Common Kestrel, Common Snipe and Stock Dove are at risk of fading from the landscape and becoming part of our collective memory. The populations of these three species have decreased so substantially that they have recently been classified as Red-listed in Ireland.

Our asks to the political parties fall under four key categories: Build resilience, Supporting farmland birds and farmers, Protecting our seabirds and the opportunities in our seas and Protecting and restoring nature for people, wildlife and climate goals. These asks include (click here for a full list of proposals):

- Fund a Farmland Bird Monitoring Programme as a better reflection than the common farmland bird index of how threatened, Red-listed farmland birds are doing.

- Ensure that farmers can stay on the land by properly funding measures in Ireland’s agri-environment schemes to pay farmers for the valuable ecosystem services they provide including the protection and restoration of farmland bird populations.

- Designate marine Special Protection Areas for birds based on BirdWatch Ireland and BirdLife International Important Bird Areas mapping. Ensure robust management plans for these areas are established and resourced.

- Publish and pass strong and effective Marine Protected Area legislation as soon as possible.

- Ensure that the essential and critical roll out of renewable energy and new ‘renewable energy acceleration areas’ are underpinned by robust bird sensitivity mapping to avoid threats to wild bird populations.

- Establish and resource an effective Wildlife Crime Unit.

- Design, fund and implement an ambitious National Nature Restoration Plan which will set nature on the pathway to recovery and supported by an expert working group, including environmental organisations like BirdWatch Ireland.

Curlew EIP harnesses people-power to help stem population declines

The Irish Breeding Curlew European Innovation Project (EIP) may be wrapped up and the final report written, but its impact is sure to be felt for years to come.

A multi-partnership project involving BirdWatch Ireland, the Irish Natura and Hill Farmers Association (INHFA), the Irish Grey Partridge Conservation Trust and Teagasc, the Curlew EIP looked to address factors contributing to the decline of breeding Curlew in Ireland. Working closely with the farming community in South Leitrim and South Lough Corrib, the project developed and trialled new and innovative approaches to help stem the decline of Ireland’s breeding Curlew population.

Predation of nests and chicks is also known to be one of the main reasons for the decline of Curlew populations. To address this The Curlew EIP developed “Conservation Keepering”, a tool which placed international best practice, ethics and standards in predator management at its core. It trialled the Conservation Keepering Option, an agri-environmental measure with 33 farmers over four years from 2020 to 2023. Through this innovative approach, farmers carried out predator management to reduce predator populations in and around important Curlew breeding sites during the breeding season, and provided landscape-level support to the project’s Conservation Keepers.

Predation of nests and chicks is also known to be one of the main reasons for the decline of Curlew populations. To address this The Curlew EIP developed “Conservation Keepering”, a tool which placed international best practice, ethics and standards in predator management at its core. It trialled the Conservation Keepering Option, an agri-environmental measure with 33 farmers over four years from 2020 to 2023. Through this innovative approach, farmers carried out predator management to reduce predator populations in and around important Curlew breeding sites during the breeding season, and provided landscape-level support to the project’s Conservation Keepers.

Innovative approaches

Breeding Curlew represent one of the highest conservation priorities in Ireland, with only 105 confirmed breeding pairs recorded during the 2021 National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) survey. This represents a 98% decline in breeding pairs in the Republic of Ireland since the 1980s. Habitat loss and degradation (as a result of agricultural intensification, land drainage and afforestation) has been identified as one of the primary threats to breeding Curlew populations in Europe and, though multi-faceted, addressing this was a key element of the Irish Breeding Curlew EIP. Over three years (2020 – 2022), 35 farmers trialled the “Curlew Habitat Option”– a results-based agri-environmental measure to manage Curlew breeding habitat that was supported with the provision of specialist advice and farmer training. Capital Works were also developed and trialled to support this measure and improve breeding habitat by, for example, removing scrub or creating chick feeding habitat. Participating farmers were financially rewarded for delivering high-quality Curlew breeding habitat, with payment levels linked to annual field scores. Breeding season sward height, wet features (suitable for chick feeding), scrub encroachment and predator habitat were some of the elements scored. Project results showed a highly significant statistical increase in field scores (and therefore habitat quality) on fields entered into the Curlew Habitat Option for at least two years, in both Leitrim and Lough Corrib. Farmer training and support was shown to be a key factor in the achievement of habitat improvements (and increasing field scores). In the first year of the scheme Covid-19 restrictions prevented farmer training from taking place, and 2020-2021 were the only years between which there was no significant increase in field scores. Predation of nests and chicks is also known to be one of the main reasons for the decline of Curlew populations. To address this The Curlew EIP developed “Conservation Keepering”, a tool which placed international best practice, ethics and standards in predator management at its core. It trialled the Conservation Keepering Option, an agri-environmental measure with 33 farmers over four years from 2020 to 2023. Through this innovative approach, farmers carried out predator management to reduce predator populations in and around important Curlew breeding sites during the breeding season, and provided landscape-level support to the project’s Conservation Keepers.

Predation of nests and chicks is also known to be one of the main reasons for the decline of Curlew populations. To address this The Curlew EIP developed “Conservation Keepering”, a tool which placed international best practice, ethics and standards in predator management at its core. It trialled the Conservation Keepering Option, an agri-environmental measure with 33 farmers over four years from 2020 to 2023. Through this innovative approach, farmers carried out predator management to reduce predator populations in and around important Curlew breeding sites during the breeding season, and provided landscape-level support to the project’s Conservation Keepers.

Results of the Curlew EIP

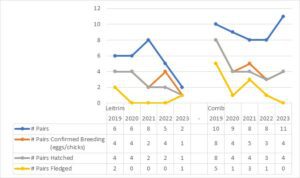

Curlew (and other breeding waders, where present) surveys were carried out between March and May annually to determine the number of confirmed, possible and probable breeding pairs, as well as breeding productivity (measured by the number of successfully fledged chicks). Populations in Corrib were stabilised over the lifetime of the project and showed some growth by 2023, increasing to 11 pairs.

Total no. of pairs, pairs confirmed breeding, hatching, and fledging by area and year.

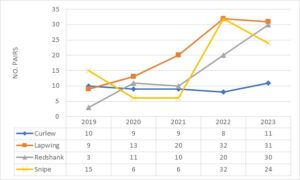

Unfortunately, a complex range of factors led to a different outcome in South Leitrim. Leitrim had poor productivity in most years and consequently, populations showed continual decline. Predator pressure and fragmented habitat due to afforestation and scrub invasion around the bogs where Curlew were breeding were shown to be impacting on breeding success. Scrub and forestry are known to hold higher numbers of predators and lead to an increase in predation of breeding Curlew (and other ground-nesting birds) for up to a kilometre from the edge of the woodland. If local populations are to be saved in Leitrim, substantial efforts will need to be made to address these issues. As an umbrella species, measures carried out to protect breeding Curlew benefit other breeding waders. Populations of three other Red-listed species of Conservation Concern – Lapwing, Redshank and Snipe – all showed a marked increase since the project began, with total populations increasing by 215 % from 27 to 85 breeding pairs.Total number of pairs for all species, by year in the Corrib project area.

Satellite Tagging breeding Curlew

The project also carried out satellite tagging of breeding Curlew to learn about their habitat usage and home range during the breeding season. Adult (mainly male) Curlew were satellite tagged allowing project staff to locate their nest and erect predator-proof fences around them, and focus their habitat and predator management work. The project also collaborated with NPWS and pooled their data for analysis on the home range size needs of Ireland’s breeding Curlew. The results of this show that breeding Curlew need a minimum of a 2km radius free from afforestation around their nest sites. It is anticipated that this work will help influence Ireland's future afforestation policy. Through satellite tagging and colour-ringing, the project also identified new information on the behaviour of non-breeding birds, which were shown to hold territory and exhibit breeding calls. This was also found to be the case with other satellite projects across the UK and Europe and it is not fully known whether these are juvenile birds learning breeding behaviour, or birds that are attempting to breed, but who have not found a mate. Only two of the 12 birds caught and colour-ringed returned to the project area in subsequent years. It is thought that this is a result of high adult mortality in an ageing population. Look out for birds with blue and white colour rings above the knee joint, with an individual marker ring on the LA – yellow and beginning with the letter A.People Power

The measures in the Curlew EIP require a team of dedicated and engaged people to carry them out. The project’s success is directly linked to the farmers and landowners across Lough Corrib and South Leitrim, whose commitment to saving the biodiversity on their farms and in their local area was key to the project's success. The interest in nature amongst members of the farming community is unquestionable, but it is vital that this is met with support, both financial and advisory, if we are to help to reverse the decline of threatened farmland bird species.Looking forward

The Curlew EIP concluded in December 2023, with many of its measures adopted into ACRES Cooperation (CP) either directly or in a revised form. Work by the Curlew EIP and by BirdWatch Ireland using its hotspot mapping showed that many important areas for breeding Curlew and other waders were located outside of ACRES CP areas and was instrumental in securing the inclusion of a National Breeding Wader EIP and a Shannon Callows EIP in Ireland’s new agri-environmental programme under the Common Agricultural Plan (CAP). The National Breeding Wader EIP comes on stream in 2024 and will provide for breeding waders nationally going forward. The Irish Breeding Curlew EIP was funded by the Department of Agriculture Food and the Marine’s, European Innovation Partnership (EIP) fund. Read the full report here: The Irish Breeding Curlew EIP - End of Project Report March 2024