In recent weeks we’ve gotten reports of some well-known Starling murmurations that are ‘back in action’ this winter. These huge gatherings actually occur all over the country, and we want your help to find out where they are! We’ve set up an online map and form, so let us know if you see a murmuration this winter! (Be sure to obey all covid-19 travel restrictions though!)

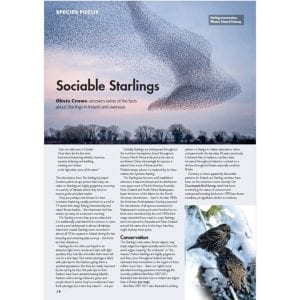

If you’ve ever gotten a good look at a Starling in the right light, you’ll have seen that far from being small black birds, that they actually have some beautiful iridescent greens, blues and purples, speckled with smart white dots. Similarly, after a few days of running outside to look for the Lapwing, Curlew, Heron or Buzzard calling over your garden, only to see a Starling perched on a telephone pole, you might have realised that Starlings are also fantastic mimics! So, what’s more impressive than a Starling? Well, it’s tens of thousands of Starlings together, swirling across the sky together in unison!

Winter Priorities

During the winter months, birds have two things to concentrate on – feeding and roosting. Feeding is obvious – find enough food to keep you going through the winter to survive to the next breeding season. The more calories and fat the better! As well as acquiring energy, it’s important not to waste energy, and you can do that by picking somewhere warm and sheltered to spend the long cold winter nights. The warmer it is, the less fat you’re burning off to keep yourself warm, and the better your chances of survival. Some birds in your garden will spend the night (‘roost’) in dense hedges and shrubs, or in old nests and nestboxes. For small species like Wrens, it’s not unusual for large numbers to pile into a nestbox to share body heat overnight. This is what we call a ‘communal roost’, albeit a small one. Other birds do this on a bigger scale – Pied Wagtails will roost in tens or even hundreds in trees in urban areas, where temperatures are warmer than the surrounding countryside. Rooks and Jackdaws will meet up in the evening and form large roosts where they’ll be warm and they can also exchange information about good feeding places. Starlings really take this to the extreme though and will roost together in their tens of thousands during the winter months.

How to find your local Starling roost

Often they’ll roost in reedbeds around lakes, in woods or forestry, and in some cases in Northern Ireland and the UK on bridges, large buildings and seaside piers. There are some well-known Starling roost locations used each year – for example Lough Ennell in Westmeath, near Nobber in Meath, Timoleague in Cork, Lackagh in Galway and Lough Ree in Roscommon. These might be used for part or all of the winter, and the numbers can vary considerably week-to-week and month-to-month. Starlings are present all over Ireland during the winter, and they’ll travel tens of kilometres to roost at night – often 20km or more. So it’s safe to assume that there are Starling roosts and murmurations all across the country every week – so we want your help to find them! They’re often easy to track down. Keep an eye on the sky around half an hour before sunset and you’ll see groups of tens, hundreds and maybe thousands of Starlings all flying in the same direction every evening. Then think, what kind of habitat in that direction could they be heading for? Is there a big lake with a reedbed? Maybe there’s a substantial area of woodland? Maybe it’s some large urban building, or possibly even a rugged cliffside? A bit of detective work later and you’ll track it down in no time! And once you do, let us know via the link here. We can’t stress enough how important it is to obey all government advice and restrictions concerning the pandemic and we don’t want anyone breaching those guidelines in search of Starlings. But, if you’re lucky enough to spot a murmuration near you then please let us know.

You’re not the only one watching…

Unfortunately, Starlings don’t put on a show every time. They roost together in large numbers every night, but it’s the aerial dance beforehand that we refer to as a ‘murmuration’, so that bit isn’t always guaranteed. These mesmerising movements across the sky, twisting and turning and creating all sorts of unimaginable shapes and patterns, have the effect of signalling to other Starlings to where they should roost, but it also makes it very difficult for predators to focus in on any one bird. These huge flocks regularly attract a who’s who of birds of prey – Peregrine Falcons, Merlins, Kestrels, Sparrowhawks and even Hen Harriers and Short-eared Owls! If there’s tens of thousands of Starlings present, then the birds of prey will fancy their chances of getting an evening meal before heading off to roost themselves. From a Starlings point of view though, the more Starlings present then the lower the risk is to each individual Starling. If there’s 10,000 Starlings present, and let’s say two Peregrines and a Sparrowhawk all on the hunt, then the chances of any individual Starling being the one who gets caught is only 0.03% – pretty good odds! If you see any birds of prey at your local murmurations, be sure to include the details and species when you submit your record!

A physicist, a biologist and a computer scientist walk into a reedbed…

Scientists have done a lot of work to figure out exactly how Starlings manage these aerial displays without crashing into each other. Instead, their movements appear coordinated, while seemingly moving in random directions and being able to react quickly and get out of the way of a stooping Peregrine or a Sparrowhawk whizzing by. Flocks split and merge, move left and right, up and down, high in the sky before suddenly dropping low over the ground, all without a single collision. Thanks to the combined efforts of behavioural biologists, computer scientists and theoretical physicists, we now know that each Starling is reacting to the movements of the nearest seven or so neighbours in the flock. If every Starling is doing that, then you get the pulses and waves, and quick reactions that we’re often treated to in these murmurations.

An international affair

Many of these Starling roosts can number tens of thousands of individuals. The Irish-breeding population has recently been estimated at around 2 million individuals, and if you add in this year’s juveniles you’re talking at least 3 million ‘Irish’ Starlings. In winter though, our Irish-breeding birds are joined by Starlings from as far away as Russia, Finland, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, as well as the UK. Ireland is one of the few European countries with a stable Starling population, so let these magnificent murmurations be a reminder of how lucky we are to have them!

Don’t forget, submit your records of Starling murmurations via the link here. We don’t need an exact count, but a ballpark estimate is useful, and we welcome multiple records from the same locations through the winter!

Thanks to Edward Delaney for the murmuration photographs used in this article.

To read more about Starlings in Ireland, including their murmurations, see the article below from the Winter 2014 edition of our ‘Wings’ magazine, which is sent to all BirdWatch Ireland members four times per year.