You’re probably used to seeing a similar suite of species in your garden each year, but have you ever wondered how old the bird you’re looking at might be?

How long have you been living in that house, and how many generations of Blackbirds or Goldfinches might you have been watching over the years? What about the confiding Robin that watches you put food on the bird table every morning, is that the same bird as last year? What about 3 years ago? 5 years ago? More? Thankfully, decades of research in Ireland, the UK, and further afield means we can answer those questions!

The Irish Garden Bird Survey is kindly sponsored by Ballymaloe. Click below to learn about taking part this winter.

Let’s start with how we know how old a bird is. Like ageing a tree, we rely on rings… we don’t cut them in half though… that kind of thing is fine in dendrology but is frowned upon at best in ornithology! Bird ringing is the study of birds by catching them and fitting them with a small metal ring around their leg. Each ring has a unique code, so that bird won’t be mixed up with another one if it’s seen again. The ring weighs only a small percent of the birds body weight, so doesn’t bother them or weigh them down, and it’s the bird equivalent of wearing a watch in that you quickly forget you’re wearing it at all. Once a bird is ringed, you’re relying on seeing or catching it again to learn about their survival and lifespan (i.e. by the amount of time elapsed since ringing).

Birds are biologically programmed to make the passing of their genes a high priority! There are two different ‘strategies’ to achieve that. One option is to live a long time and concentrate on raising one or two chicks per year over your lifetime. Seabirds generally employ this strategy. For example, a Manx Shearwater can live up to 50 years old but won’t start breeding until 5 years and after that will raise a single egg/chick each year. The ‘slow and steady’ approach. The other option is to live a short amount of time, but to produce multiple large broods of chicks in the few summers you have. The live fast, die young approach. Blue Tits do this – they can live up to only around 10 years at a maximum, but breed the summer after they hatched, and produce clutches of 8-10 eggs. Mortality will be high for these chicks, but if even a fraction of them survive then they’re passing on their genes successfully and at a similar rate to the Manx Shearwater!

Blue Tit caught under BTO and NPWS license, to help us learn more about this species – including how long they live.

Blue Tit caught under BTO and NPWS license, to help us learn more about this species – including how long they live.

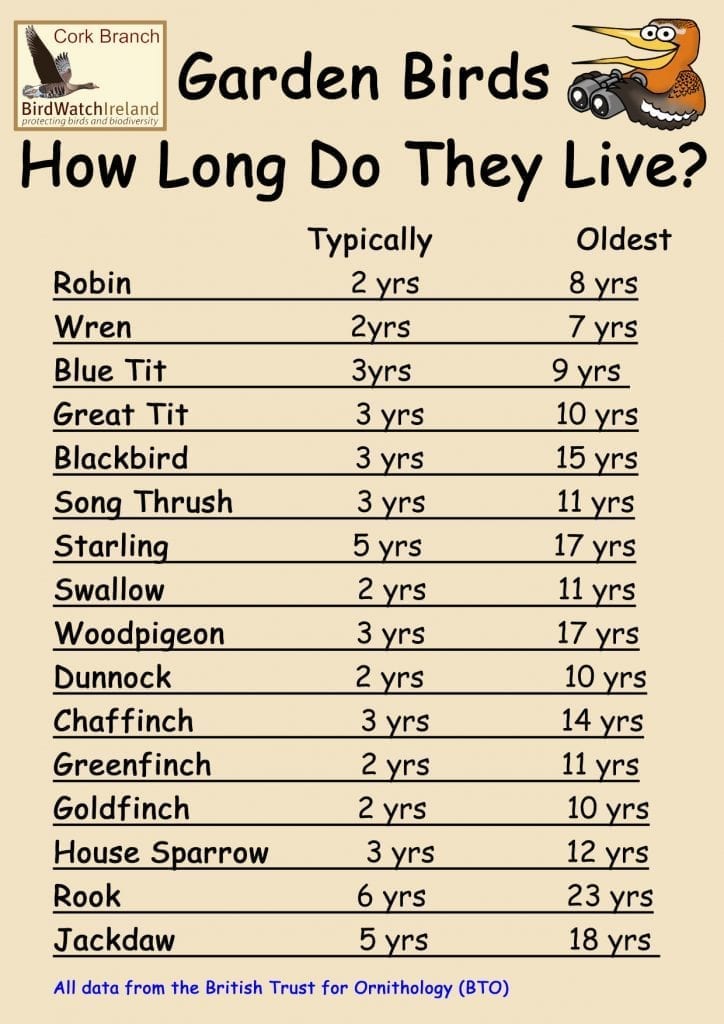

Most of our garden birds follow the same strategy as the Blue Tit. They might not live as long as you expect on average, but they make the best of each and every breeding season! See below a poster prepared by BirdWatch Ireland’s Cork Branch, based on data from the BTO ringing scheme which covers Ireland and Britain.

Is there anything in there that surprises you?

For most of our smaller garden species, they live 2 or 3 years, so that’s why every breeding season is important! Some of those same birds can in theory live to 8-12 years, but they are very much the exception rather than the rule. Take Blue Tit as an example – around 5 million Blue Tits have been ringed in Britain and Ireland since 1909, and only a fraction of a percent have made it to 9 years old, and none have survived to 10 years. Blue Tits are a very sedentary species, meaning they don’t travel far, so there’s a good chance a ringed Blue Tit will be seen or caught again if they’re alive, meaning we can have huge confidence in the figures above. For some species, older individuals have been ringed and re-caught elsewhere in their range (e.g. an 11 year 7 month old Blue Tit was caught in the Czech Republic), but the pattern is still very much the same with little variation.

The oldest Jackdaw on record from Britain and Ireland is from Edenderry in Offaly. It was first caught in 1999, and again in the same garden in 2005, 2007, 2012 and 2017, making it over 18 years old when it was last seen.

It’s somewhat intuitive that the larger species live longer. Amongst the small garden birds, the likes of Chaffinch, Greenfinch and House Sparrow are some of the biggest and heaviest and they tend to get a bit longer than the smaller Blue Tits, Wrens and Robins. The medium-sized Blackbirds, Song Thrushes and Starlings generally get 3-5 years, and are capable of 10-15 years if things go their way! Rook, Jackdaw and Woodpigeon generally live quite a bit longer than the smaller birds. If we have a cold winter, who is going to suffer worst? The Rook, with a smaller surface to body ratio meaning it can hold in heat, a flexible diet and big wings to easily fly a few kilometres to find food if needs be, or something small like a Wren or Blue Tit which falls on the opposite end of the spectrum for all of those considerations? High winter mortality, particularly for juvenile birds, is likely to bias those average/typical figures somewhat. That is to say, if a Robin survives that first winter then there’s a good chance it might make it to 4 or even 5 years old. The good news is that if you’re feeding your garden birds through the winter, and maintaining hedges and trees to provide adequate shelter, food and nest space, then you’re helping your local bird community to beat the averages, live longer and raise more young. What more motivation do you need?!

If you’re curious about how long some other bird species live, see the BTO website here for birds in Ireland and Britain, and the EURING website here for records from across Europe.

The Irish Garden Bird Survey is running right now and taking part couldn’t be easier! Click here for full details about the survey as well as as advice on caring for your birds through the winter.

This winter we’re running a series of blogs like this one, filled with facts and figures about your favourite garden birds, click here for more.

We are hugely grateful to Ballymaloe for their sponsorship and support of the Irish Garden Bird Survey.

Click below to download your count form for this year’s Irish Garden Bird Survey.

Blue Tit caught under BTO and NPWS license, to help us learn more about this species – including how long they live.

Blue Tit caught under BTO and NPWS license, to help us learn more about this species – including how long they live.