Grey Plover

| Irish Name: | Feadóg ghlas |

| Scientific name: | Pluvialis squatarola |

| Bird Family: | Waders |

red

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

Winter visitor from Siberia - first birds arrive in Ireland and Britain towards the end of July but most here between September & April.

Identification

Big and bulky plover, large head and heavy bill. Posture hunched and feeding action pondorous. Black axilliaries, bold white wing-bar and white rump diagnostic in flight.

Voice

Call is mournful, trisyllabic whistle, the middle lower-pitched, occasionally stressed - 'peee-uu-ee'.

Diet

Feeds on a wide variety of burrowing intertidal invertebrates, particularly polychaete worms, molluscs and crustaceans.

Breeding

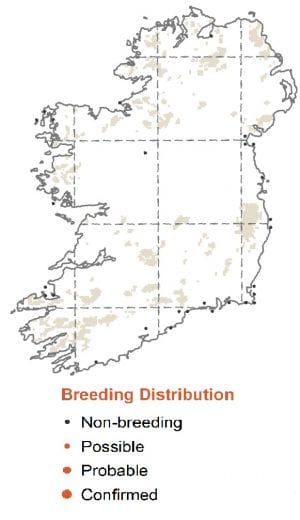

Breeds across the high arctic regions of Russia & North America

Wintering

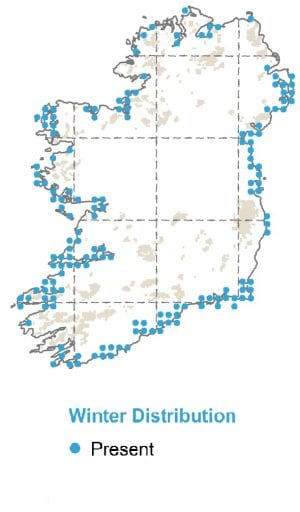

Distribution in Ireland is widespread, but exclusively coastal. They occur mostly along eastern and southern coasts, most often on large muddy estuaries. They regularly roost among dense flocks during high tide, while their distribution is more scattered while feeding.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

Extinction of Slender-billed Curlew must be a wake-up call for global biodiversity action

In recent days, scientists sounded the death knell for Slender-billed Curlew, declaring the migratory shorebird globally extinct.

Published in IBIS, the International Journal of Avian Science, the analysis of the Slender-billed Curlew’s conservation status was a collaboration between RSPB, BirdLife International, Naturalis Biodiversity Centre and the Natural History Museum.

This is the first known global bird extinction from mainland Europe, North Africa and West Asia and, unless biodiversity loss is treated as the crisis that it is, it won’t be the last.

Indeed, the extinction of the Slender-billed Curlew should serve as a wake-up call to protect other vulnerable species from a similar fate.

What happened to the Slender-billed Curlew?

The Slender-billed Curlew was a migratory shorebird that once bred in western Siberia and wintered around the Mediterranean. A brown and beige wading bird similar in appearance to the Eurasian Curlew, it was distinguished by a striking flash of white under its tail, visible only in flight. As noted in the IBIS paper, records suggest that the Slender-billed Curlew was in decline as early as 1912, with the possibility of the species becoming extinct raised as early as the 1940s. However, it was not until 1988 that the species was identified as being of high conservation concern and classified as Threatened. The last undisputed sighting of the Slender-billed Curlew was in Morocco in 1995, despite extensive and intensive searches for the species since then. The recent research concludes that there is a 99.6% chance that this bird is now extinct. While the paper notes that the factors that led to the Slender-billed Curlew’s decline may never be fully understood, it points to possible pressures including extensive drainage of their raised bog breeding grounds for agricultural use, the loss of coastal wetlands used for winter feeding, and hunting, especially latterly, of an already reduced, fragmented and declining population. There could have been impacts from pollution, disease, predation, and climate change, but the scale of these impacts is unknown. Alex Berryman, Red List Officer at BirdLife International, and a co-author of the study, said; “The devasting loss of the Slender-billed Curlew sends a warning that no birds are immune from the threat of extinction. More than 150 bird species have become globally extinct since 1500. Invasive species have often been the culprit, with 90% of bird extinctions impacting island species. However, while the wave of island extinctions may be slowing, the rate of continental extinctions is increasing. This is a result of habitat destruction and degradation, overexploitation and other threats. Urgent conservation action is desperately needed to save birds; without it we must be braced for a much larger extinction wave washing over the continents.” It is now up to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to determine whether to officially declare this species extinct.Global shorebird declines

This news comes just weeks after an IUCN report revealed steep declines for migratory shorebird populations globally. 16 species of shorebird, including several species that winter in Ireland and are monitored through the Irish Wetland Bird Survey (I-WeBS), have had their conservation status reclassified to a higher threat category in the latest IUCN Red List update. Grey Plover, Dunlin and Ruddy Turnstone are among the species affected. Additionally, we know the seven other Curlew species share more than a name with the Slender-billed Curlew. Indeed, many other species of Curlew are experiencing declines. The last known sighting of an Eskimo Curlew was in 1963, when a lone bird was shot in Barbados. It is presumed to be extinct. Closer to home, the Eurasian Curlew has plummeted by over one-third in just 30 years, while central Asian populations have also experienced significant declines. Once a widespread breeding species in Ireland, a 2021 National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) survey reported just 105 confirmed breeding pairs of Eurasian Curlew. This represents a 98% decline in breeding pairs in the Republic of Ireland since the 1980s. Habitat loss and degradation (as a result of agricultural intensification, land drainage and afforestation) have been identified as the primary threats to breeding Curlew populations in Europe. For decades, BirdWatch Ireland has spearheaded surveys and conservation efforts for Curlew and other breeding waders in Ireland. We also advocated for the introduction of a multi-million euro scheme which supports farmers to undertake measures aimed at saving Ireland’s breeding waders from extinction. We are pleased that the Government has responded, with the introduction of the Breeding Wader EIP earlier this year.Extinction in real-time

The devastating loss of the Slender-billed Curlew serves as a stark reminder that extinction is not some far-away concept. It is happening in real-time, on our watch, and within our own country. The Corn Bunting, a once common farmland bird, has been extinct in Ireland since the 1990s. Species such as the Hen Harrier are on the brink of extinction, with only 85-106 breeding pairs believed to remain in the country, while just one known pair of Ring Ouzel remains in Ireland. As previously mentioned, Ireland's breeding population of Eurasian Curlews is also in critical danger. Scientists know what needs to be done to reverse species declines and it is up to global leaders to step up and take meaningful action. This work must be collaborative and inclusive if it is to be effective. Migratory birds cross borders, so conservation efforts in one country can be undone by harmful actions in another that shares the same species.Giving nature a voice

Extinction is permanent. While it may be too late for the Slender-billed Curlew, some hope remains for countless other species, if we act quickly and decisively. As a member of the public, your choices and voice can help protect the future of many species still at risk. As we approach a General Election in Ireland, we encourage our supporters to prioritise the issues of biodiversity loss and climate change when engaging with and voting for their General Election candidates. You can find our list of asks for people, nature and climate in the next Government here. Featured Image: Slender-billed Curlew Morocco, Chris-Gomersall/rspb-images.com.

New IUCN report reveals plummeting migratory shorebird populations globally

16 species of shorebird, including several species that winter in Ireland and are monitored through the Irish Wetland Bird Survey (I-WeBS), have had their conservation status reclassified to a higher threat category in the latest IUCN Red List update.

The latest update to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ reveals a highly concerning decline in populations of migratory shorebirds across the globe, with 16 species reclassified to higher threat categories1. Some populations of migratory shorebirds have decreased by more than a third.

Among the species that have experienced declines are Grey Plover, a species that winters in Ireland from Siberia. While it remains a widespread and abundant species, its status has been changed from “Least Concern” to “Vulnerable” in response to increasing evidence for rapid population declines over the past three generations (23 years), estimated to be more than 30%. The exact causes of these declines are unknown, but a myriad of plausible threats have been identified including habitat loss and degradation, disturbance and hunting.

The Dunlin, a winter visitor to our shores from Scandinavia to Siberia, has also been reclassified from “Least Concern” to “Near Threatened”. This small shorebird has declined moderately rapidly according to recent monitoring. There is considerable uncertainty in the rate of the reduction, but it is suspected to fall between 20-29% over the past three generations and for the period projected to the near future, according to the IUCN report. At present, the population size and range remain large but due to the rate of population reduction, the species is now listed as “Near Threatened”.

The Ruddy Turnstone has also been reclassified in the latest IUCN report, from “Least Concern” to “Near Threatened”. A winter visitor to Ireland from northeast Canada and northern Greenland, this bird is a widespread species with a global population of 750,000-1,750,000 mature individuals. However, the Ruddy Turnstone faces a myriad of threats across its vast range, including habitat loss and degradation, illegal killing, disturbance and possibly reduced breeding productivity caused by factors associated with climate change. While the relative importance of these threats is unknown, monitoring data in several parts of its range, particularly in North America, indicate locally rapid declines over the past three generations. The global population is thought to have declined moderately rapidly, at a rate 20-29% over the past three generations (18 years).

Several species of sandpiper have been reclassified to higher threat categories, including the Curlew Sandpiper – a scarce passage migrant to Ireland. Recent monitoring data have shown that this widely distributed species has probably declined by 30-49% over the past three generations (15 years). The exact causes of declines are unknown, but are likely to include habitat loss and degradation (particularly on stopover and wintering grounds) and climate change impacts (particularly affecting breeding productivity), as well as disturbance and hunting. As a result of these population changes, the Curlew Sandpiper has been reclassified from “Near Threatened” to “Vulnerable”.

Birds are important indicators of the state of nature: they occur almost everywhere, their behaviours and ecology often mirror other groups of species, they are extremely well studied, and they are responsive to environmental change. Many migratory birds follow specific routes called flyways, stopping at various sites along the way to rest and feed. This makes them especially at risk from threats like habitat loss and climate change.

Science shows the huge negative impact of declining species populations, with whole ecosystems and food chains being disrupted as a result. As birds migrate beyond borders, the new update highlights a need for more collaboration from governments without delay to reverse the losses of migratory birds.

Together with BirdLife International and our BirdLife partners across the globe, BirdWatch Ireland is calling on governments at CBD COP16 to step up urgent actions for species to reverse declines and stop extinctions.

Martin Harper, CEO, BirdLife International said: “COP16 must be the catalyst for governments to back up commitments made two years ago with meaningful action to reverse the catastrophic declines in species populations. This means more action to bolster efforts to recover threatened species, more action to protect and restore more land, freshwater and sea, and more action to transform our food, energy and industrial systems – backed up by the necessary funding. The decline of migratory birds, which connect people across countries and continents, is a powerful symbol of how we are currently failing.”

We only have five more years of this defining decade. CBD COP16 is the moment to galvanise action to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030. Plummeting migratory bird populations signal that nature is in crisis. When we lose species, our future is compromised. Nature loss can be reversed but extinctions cannot.