Hen Harrier

| Irish Name: | Cromán na gCearc |

| Scientific name: | Circus cyaneus |

| Bird Family: | Raptors |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

Breeds in the uplands and bogs of Ireland.

Identification

Size between Montagu's Harrier and the larger Marsh Harrier. Females and juveniles similar - brown with white rump and dark rings on the tail, hence often referred to collectively as 'ringtails'. Females are bigger than males. Males very distinctive, appearing strikingly pale below, with blue grey upper parts and jet black wing-tips. Hen Harriers have somewhat of an owl-like face, particularly accentuated in female birds.

Voice

Usually only heard in the breeding season near the nest site. Quick, chattering calls in alarm and display and whistling calls from female to male, when receiving food.

Diet

Small birds and mammals, which are caught by surprise. Will sometimes use cover, such as woodland edges and bushes, to surprise prey.

Breeding

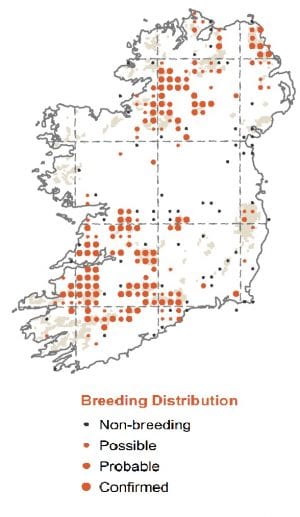

Breeding birds are confined largely to heather moorland and young forestry plantations, where they nest on the ground. Hen Harriers are found mainly in Counties Laois, Tipperary, Cork, Clare, Limerick, Galway, Monaghan, Cavan, Leitrim, Donegal and Kerry. The species has declined, probably due to the loss of quality moorland habitat due to agricultural changes, and maturing forest plantations. Hen Harriers mainly hunt over moorland whilst breeding where they take small ground nesting birds and mammals.

Wintering

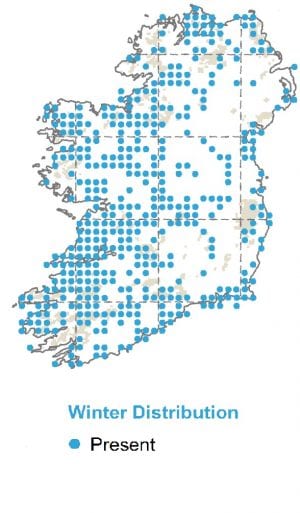

Spends winter in more coastal and lowland areas throughout Ireland hence most easily seen on the coast in the winter months. Good sites include the North Slob Nature Reserve and Tacumshin Lake in County Wexford, as well as the East Coast Nature Reserve in Co. Wicklow.

Monitored by

BirdTrack and the Hen Harrier Roost Survey.

Blog posts about this bird

Extinction of Slender-billed Curlew must be a wake-up call for global biodiversity action

In recent days, scientists sounded the death knell for Slender-billed Curlew, declaring the migratory shorebird globally extinct.

Published in IBIS, the International Journal of Avian Science, the analysis of the Slender-billed Curlew’s conservation status was a collaboration between RSPB, BirdLife International, Naturalis Biodiversity Centre and the Natural History Museum.

This is the first known global bird extinction from mainland Europe, North Africa and West Asia and, unless biodiversity loss is treated as the crisis that it is, it won’t be the last.

Indeed, the extinction of the Slender-billed Curlew should serve as a wake-up call to protect other vulnerable species from a similar fate.

What happened to the Slender-billed Curlew?

The Slender-billed Curlew was a migratory shorebird that once bred in western Siberia and wintered around the Mediterranean. A brown and beige wading bird similar in appearance to the Eurasian Curlew, it was distinguished by a striking flash of white under its tail, visible only in flight. As noted in the IBIS paper, records suggest that the Slender-billed Curlew was in decline as early as 1912, with the possibility of the species becoming extinct raised as early as the 1940s. However, it was not until 1988 that the species was identified as being of high conservation concern and classified as Threatened. The last undisputed sighting of the Slender-billed Curlew was in Morocco in 1995, despite extensive and intensive searches for the species since then. The recent research concludes that there is a 99.6% chance that this bird is now extinct. While the paper notes that the factors that led to the Slender-billed Curlew’s decline may never be fully understood, it points to possible pressures including extensive drainage of their raised bog breeding grounds for agricultural use, the loss of coastal wetlands used for winter feeding, and hunting, especially latterly, of an already reduced, fragmented and declining population. There could have been impacts from pollution, disease, predation, and climate change, but the scale of these impacts is unknown. Alex Berryman, Red List Officer at BirdLife International, and a co-author of the study, said; “The devasting loss of the Slender-billed Curlew sends a warning that no birds are immune from the threat of extinction. More than 150 bird species have become globally extinct since 1500. Invasive species have often been the culprit, with 90% of bird extinctions impacting island species. However, while the wave of island extinctions may be slowing, the rate of continental extinctions is increasing. This is a result of habitat destruction and degradation, overexploitation and other threats. Urgent conservation action is desperately needed to save birds; without it we must be braced for a much larger extinction wave washing over the continents.” It is now up to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to determine whether to officially declare this species extinct.Global shorebird declines

This news comes just weeks after an IUCN report revealed steep declines for migratory shorebird populations globally. 16 species of shorebird, including several species that winter in Ireland and are monitored through the Irish Wetland Bird Survey (I-WeBS), have had their conservation status reclassified to a higher threat category in the latest IUCN Red List update. Grey Plover, Dunlin and Ruddy Turnstone are among the species affected. Additionally, we know the seven other Curlew species share more than a name with the Slender-billed Curlew. Indeed, many other species of Curlew are experiencing declines. The last known sighting of an Eskimo Curlew was in 1963, when a lone bird was shot in Barbados. It is presumed to be extinct. Closer to home, the Eurasian Curlew has plummeted by over one-third in just 30 years, while central Asian populations have also experienced significant declines. Once a widespread breeding species in Ireland, a 2021 National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) survey reported just 105 confirmed breeding pairs of Eurasian Curlew. This represents a 98% decline in breeding pairs in the Republic of Ireland since the 1980s. Habitat loss and degradation (as a result of agricultural intensification, land drainage and afforestation) have been identified as the primary threats to breeding Curlew populations in Europe. For decades, BirdWatch Ireland has spearheaded surveys and conservation efforts for Curlew and other breeding waders in Ireland. We also advocated for the introduction of a multi-million euro scheme which supports farmers to undertake measures aimed at saving Ireland’s breeding waders from extinction. We are pleased that the Government has responded, with the introduction of the Breeding Wader EIP earlier this year.Extinction in real-time

The devastating loss of the Slender-billed Curlew serves as a stark reminder that extinction is not some far-away concept. It is happening in real-time, on our watch, and within our own country. The Corn Bunting, a once common farmland bird, has been extinct in Ireland since the 1990s. Species such as the Hen Harrier are on the brink of extinction, with only 85-106 breeding pairs believed to remain in the country, while just one known pair of Ring Ouzel remains in Ireland. As previously mentioned, Ireland's breeding population of Eurasian Curlews is also in critical danger. Scientists know what needs to be done to reverse species declines and it is up to global leaders to step up and take meaningful action. This work must be collaborative and inclusive if it is to be effective. Migratory birds cross borders, so conservation efforts in one country can be undone by harmful actions in another that shares the same species.Giving nature a voice

Extinction is permanent. While it may be too late for the Slender-billed Curlew, some hope remains for countless other species, if we act quickly and decisively. As a member of the public, your choices and voice can help protect the future of many species still at risk. As we approach a General Election in Ireland, we encourage our supporters to prioritise the issues of biodiversity loss and climate change when engaging with and voting for their General Election candidates. You can find our list of asks for people, nature and climate in the next Government here. Featured Image: Slender-billed Curlew Morocco, Chris-Gomersall/rspb-images.com.

Nightjar confirmed to be breeding in the south-east

Nightjar and their nests are perfectly camouflaged and typically go unnoticed. Ben Andrews (rspb-images.com).

A recent survey conducted in the southeast has successfully confirmed that one of Ireland's rarest and most elusive birds, the nocturnal Nightjar, continues to breed in the country, though in very limited numbers.

With only sporadic records of breeding over recent decades, mostly in the south and south-east, the general consensus was that we had effectively lost Nightjars, despite few attempts to prove otherwise. However, a new survey coordinated by BirdWatch Ireland and supported by Kilkenny County Council, Wexford County Council and the National Parks and Wildlife Service through the Local Biodiversity Action Fund confirms that this species still survives in the southeast. The mysterious and elusive Nightjar is one of our most intriguing birds. A summer visitor with perfectly camouflaged bark-like plumage, it can be incredibly difficult to spot, only revealing its presence after dark, when the male engages in it’s hypnotic ‘churring’ song.

A Male Nightjar 'churring' from a tree stump in the night. Photo: Mike Brown.

Nightjars were once more common and widespread in Ireland, their rising and falling song was so widely-known that the bird was given its own name, Túirne Lín, meaning spinning-wheel. However, the numbers completing the journey to Ireland from African wintering grounds each May have diminished dramatically. This is thought to be related to habitat loss and a decrease in large insects due to the use of pesticides. Nightjars feed on moths and other flying insects, and they are well equipped for this: they have very large eyes adapted for hunting in low light, and a wide-gaping mouth designed to capture insect prey in flight. As the Nightjars ‘churring’ has faded from popular memory and from most of its former range, the species has slipped into relative obscurity, which is somehow fitting for a secretive bird adapted to disappear into its surroundings. We have mourned the declines of species such as Curlew, Hen Harrier and Ring Ouzel, but the disappearance of Nightjar has largely gone unnoticed. The uncertainty over the status of Nightjar in Ireland set the scene for a survey undertaken this summer. The aim of the survey was to try and confirm whether Nightjar still remain in Ireland and in the process, to learn more about this enigmatic species to help inform its conservation. The Nightjar survey was coordinated by BirdWatch Ireland and concentrated on some of the most suitable remaining areas for Nightjar in Counties Kilkenny and Wexford. Conservation Officer with BirdWatch Ireland John Lusby, who coordinated the efforts, explained how the survey was carried out: “We used acoustic recording devices which were set to record bird song in the late evening and throughout the night in areas deemed to be suitable for Nightjar, which were typically low-lying hills with forest plantation and especially recently clear-felled forest surrounded by suitable foraging habitat, in the hope that we would detect the very distinctive and unmistakable song of Nightjar, thereby confirming its presence in an area”.

Nightjar on a branch at dusk. Photo: Ben Andrews (rspb-images.com).

These survey efforts were rewarded when, within the many hundreds of hours of recordings, and among the songs and calls of many other bird species, the fabled churring of Nightjar was detected from not one but two of the survey sites. Subsequent monitoring of these sites provided confirmation that one of these pairs bred successfully, marking what appears to be the only known Nightjar successful nesting in the country. Colin Travers, one of the lead surveyors for the Nightjar survey, commented,: “It was such an amazing privilege to listen to Nightjar ‘churring’, although I was not previously familiar with this magical song, it felt natural to be listening to it in the Irish landscape, and obviously the significance of hearing their churring cannot be overstated, as it is telling us in very simple terms that even if we have somewhat forgotten about Nightjars, they are still here”. Although Nightjar numbers do appear to be extremely low in Ireland, there is some hope if we look to nearby Wales and other countries where conservation efforts have proved successful and where Nightjar populations are recovering. John Lusby, commented: “Now we know that Nightjar are still here, we need to do all we can to make sure we don’t lose them, which should include protecting and enhancing the nesting and foraging habitats at the sites where they are known to occur as well as other areas which have the potential to host Nightjar, hopefully this will help to ensure that birds will return to these areas next May and in future summers and expand out to other areas”.

Nightjar roosting during the day on a log. Photo: Andrew Hay (rspb-images.com).

Bernadette Moloney, Biodiversity Officer with Kilkenny County Council, who supported the Nightjar survey, commented: “It is incredibly important to understand what biodiversity we have and to protect what we have remaining. This survey served to highlight the biodiversity importance of some sites in the south-east which have otherwise not received much attention and are not part of our network of protected sites and it is wonderful to know that Nightjar still remain in these areas”. Claire Goodwin, Biodiversity Officer with Wexford County Council said: “We were delighted to support this survey with the assistance of funding through the Local Biodiversity Action Fund and it is brilliant news to learn that there were two pairs identified, one pair breeding successfully. Whilst this is marvellous news the low numbers highlight the fragility of the species and the urgent need for protection and conservation of their habitat”. Here is a video which showcases the survey efforts invested to find Nightjar in the south-east. https://youtu.be/R00gkg5Qx_4