Dunlin

| Irish Name: | Breacóg |

| Scientific name: | Calidris alpina |

| Bird Family: | Waders |

red

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

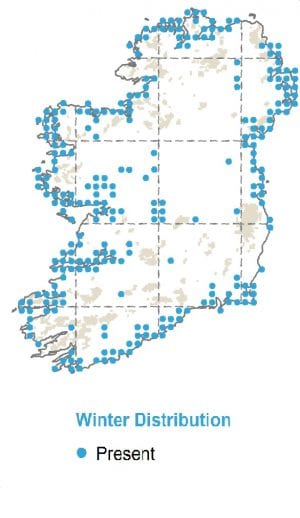

Summer visitor from NW Africa/SW Europe, winter visitor from Scandinavia to Siberia, passage migrant from Greenland (heading south to winter in Africa). Most occur during the mid-winter period.

Identification

One of the smaller waders and our most abundant one in winter and on passage. A limited number breed in some sandy / grassy locations along the west and north coasts. Plumage is highly variable - in summer, rich chestnut above, streaked on breast, white below with a striking black patch on the belly. The more usually encountered winter plumage bird shows a rather non-descript, uniform, plain brownish-grey on all upperparts and cold white underparts. Juveniles in autumn have warm brown tones on the upperparts and considerable streaking on the breast and underparts. There are many other variations and combinations, depending on the bird's state of moult. It is a rather dumpy bird, with black legs and a longish bill which downcurves slightly. Often occurs in very large flocks. An important bird to get to know (in all its plumages) if you want to successfully identify other similar-sized waders.

Voice

A harsh churring trill - "thrrrreeep"

Diet

Feed predominantly on small invertebrates of estuarine mudflats, particularly polychaete worms and small gastropods. They feed in flocks, in the muddier sections of the estuaries and close to the tide edge.

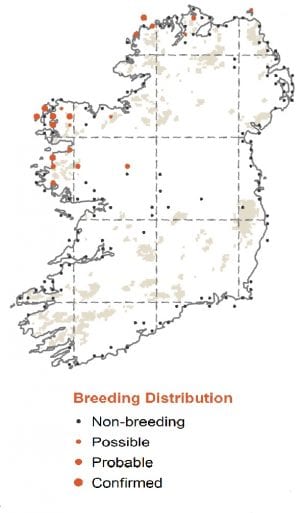

Breeding

Nests on the ground in sparse, low vegetation - in Ireland favours machair habitats

Wintering

Common along all coastal areas - especially on tidal mudflats and estuaries. Very few inland.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

PeacePlus Nature: A new cross-border project for nature recovery networks in the north west of Ireland.

BirdWatch Ireland is one of nine partners in a coalition led by RSPB NI to draw down €20m over the next four years to deliver PeacePlus Nature - an ambitious programme to tackle the decline in priority species and habitats in Northern Ireland and the border counties of Ireland. BirdWatch Ireland’s main focus in the project will be the protection and conservation of breeding waders, particularly at sites in Co. Donegal. This follows on from the work undertaken in previous Interreg projects - the Halting Environmental Loss Project (HELP, 2011-2014) and the Cooperating Across Borders for Biodiversity (CABB) Project (2017-2022).

Since 2011, BirdWatch Ireland has been active in protecting these sites - as well as undertaking surveys and monitoring, we have worked with farmers to increase their knowledge and understanding of breeding waders, supported small scale habitat works and arguably most importantly, installed a network of Predator Exclusion Fences (PEFs) across Donegal. These fences exclude mammalian predators such as foxes, badger and small mustelids from breeding colonies, comprising a physical barrier with electrified wires incorporated into the design. The fences are located at Sheskinmore in south Donegal, where BirdWatch Ireland owns part of the land enclosed, Magheragallon in Gaoth Dobhair, Rinmore on the Fanad peninsula, Long Point at Inch, where NPWS lease the land, and at nearby Blanket Nook.

Predator fence at Rinmore, Co Donegal

Our monitoring of breeding wader populations during the CABB project showed that, despite these interventions, across 37 sites in Donegal and Sligo, there was a 12% decline overall from 443 breeding pairs to 390 between 2017 and 2021. This highlights the multiple threats faced by breeding waders and the huge challenges we face to protect them. The main driver of declines is frequently predation, but disturbance, agricultural intensification, wind energy and afforestation can all have negative impacts on breeding waders and their habitats.

Lapwing at Inch (Michael Bell)

However, our monitoring also showed that the presence of a predator fence had a significant positive effect, particularly on Lapwing populations, with some fence sites seeing population increases during the period. This is a great endorsement of the work involved in installing and maintaining these fences - they are one of the few effective tools we have to protect and restore populations. Our results indicate the need to continue to focus on reducing predation, whilst also working to address other issues such as ensuring favourable habitat conditions. PeacePlus Nature will build on our success and knowledge gained from HELP and CABB, whilst also taking on some new challenges. Our main areas of work over the next four years will be: -1. Management of our network of predator fences to continue to protect and enhance breeding waders at key sites.

We will be replacing and upgrading two of the oldest PEFs at Magheragallon and Rinmore, installed in 2012/13, to make them even more effective. (NPWS are working with the Breeding Wader EIP to replace the fence at Sheskinmore). We will also continue to monitor the fences every week during the breeding season to ensure they are fully operational.

Checking electric current at predator fence

We will employ a Conservation Keeper to undertake predator control, particularly to control corvids in the vicinity of the fence sites. The Keeper will work with the existing network of keepers employed by NPWS and other projects, such as the Breeding Wader EIP, Life on Machair and Corncrake Life, to ensure synergies of effort.2. Wardening and management on Tory Island.

Tory Island is the most important site for breeding waders in the north west of Ireland, still supporting over 100 pairs and being the only site in the network to support breeding Dunlin, with about 4 breeding pairs annually. Thanks to support from Donegal County Council through the NPWS Local Biodiversity Action Fund, we were able to continue monitoring breeding waders on Tory after CABB finished in 2022; in 2024, we recorded 125 pairs, down from 172 in 2017. Predation and disturbance are likely to be the main causes. We will be employing a Warden for the island, who will work to better understand the factors affecting breeding success, ensure there is management of predators and work with the island community to reduce the impacts of recreation and disturbance.

3. Monitoring of populations

We will continue to monitor key sites every year, particularly the island sites and sites with PEFs, including monitoring of Lapwing productivity. This will help us identify successful outcomes and also areas where more intervention is needed. In 2028, we will undertake a full census of all 35 sites which we have been monitoring through HELP and CABB.

Lapwing chick within a predator fence (Michael Bell)

4. Stakeholder engagement We will be engaging closely with the other stakeholders who are working towards the protection and management of breeding waders in the north west. We will continue to work closely with NPWS – the predator fence at Long Point is on NPWS-leased land, and NPWS will be replacing the fence at Sheskinmore, which is partly on BirdWatch Ireland land. We will continue to liaise with the Breeding Wader EIP and Life on Machair to ensure synergies of effort and conservation delivery. We are already partners with Donegal Acres, which works with farmers and advisors in the Donegal Cooperation Projects (CP) area on behalf of DAFM. For some farmers, we will be able to undertake small scale works to improve habitats.Project Partners

As well at the Lead Partner - RSPB NI and BirdWatch Ireland, the other project partners include Butterfly Conservation, Monaghan County Council, River Blackwater Catchment Trust, Truagh Development Association, Lough Neagh Partnership, NI Water and An Taisce. These partners will be working together, learning from each other and sharing best practice on an exciting range of projects to restore priority habitats such as upland blanket bog and lowland wet grassland and priority species, including breeding waders, chough, corncrake, marsh fritillary and other species. We are very much looking forward to getting started on this ambitious programme of work in the coming months - we have much to do to get everything ready for the 2026 breeding season and beyond. There will be regular project updates as we go and we look forward to sharing our success with our members and supporters.PeacePlus Nature is supported by PEACEPLUS, a programme managed by the Special EU Programmes Body (SEUPB).

PEACEPLUS is supported by the European Regional Development Fund and the UK and Irish Governments.

Thanks to Donegal County Council and NPWS for funding the maintenance and monitoring of predator fences in Co. Donegal 2023-2025, through the Local Biodiversity Action Fund.

Extinction of Slender-billed Curlew must be a wake-up call for global biodiversity action

In recent days, scientists sounded the death knell for Slender-billed Curlew, declaring the migratory shorebird globally extinct.

Published in IBIS, the International Journal of Avian Science, the analysis of the Slender-billed Curlew’s conservation status was a collaboration between RSPB, BirdLife International, Naturalis Biodiversity Centre and the Natural History Museum.

This is the first known global bird extinction from mainland Europe, North Africa and West Asia and, unless biodiversity loss is treated as the crisis that it is, it won’t be the last.

Indeed, the extinction of the Slender-billed Curlew should serve as a wake-up call to protect other vulnerable species from a similar fate.