Little Grebe

| Irish Name: | Spágaire tonn |

| Scientific name: | Tachybaptus ruficollis |

| Bird Family: | Grebes |

green

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

Resident on ponds and lakes throughout Ireland.

Identification

The smallest of the grebes, Little Grebes have a very dumpy body, a short neck, tiny straight bill and no ornamental head feathers giving a rounded shape to the head. They swim buoyantly with feathers often fluffed out at rear giving a power- puff effect. In breeding adults the throat and cheeks are a bright chestnut, the fleshy gap patch takes on a pale colour and the body becomes a rich dark brown above and paler below. Out of the breeding season birds are less striking with the neck taking on a buff-brown colour and the body becoming dull brown above and paler below.

Voice

High-pitched calls with sulking birds often located by a loud whining trill, which can be heard throughout the year.

Diet

A range of invertebrates (particularly insect larvae), small fish and molluscs.

Breeding

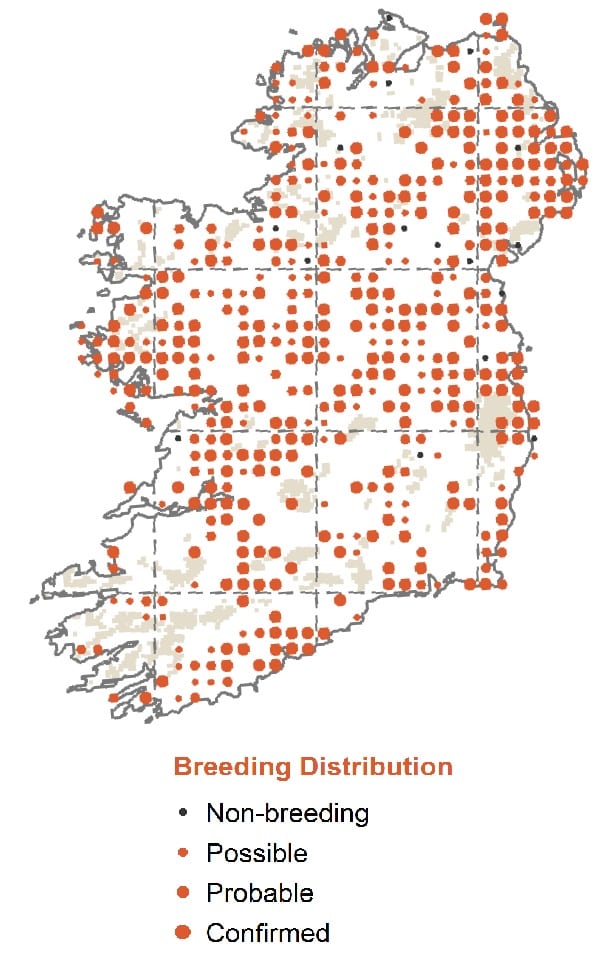

Breeding sites are relatively widely scattered with slightly higher densities in the northeast of Ireland. Pairs are highly territorial, nesting mostly on floating plant material hidden in dense vegetation at the margins of shallow, freshwater rivers, streams, loughs and ponds. They are typically shy and skulking when breeding. Some pairs occupy breeding territories throughout the years, while at some sites birds disperse from their inland breeding sites over the winter.

Wintering

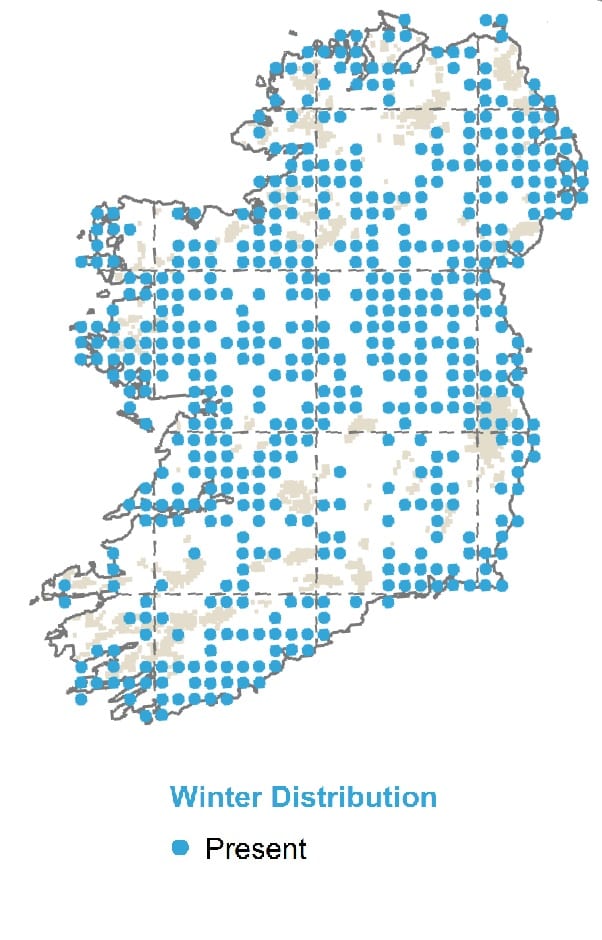

Little Grebes extend their wintering habitat to include ephemeral wetlands and are often encountered on sheltered coasts, estuaries and coastal lakes and lagoons at this time of the year.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

BirdWatch Ireland welcomes State purchase of Dowth Estate and establishment of Ireland's seventh National Park

BirdWatch Ireland welcomes the news of the State’s purchase of Dowth Hall demesne in County Meath and the establishment of the 500-acre property as a new National Park.

On Friday, Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage, Darragh O Brien TD confirmed the State’s purchase of the World Heritage lands of Dowth Hall and demesne, along with the establishment of a new National Park – the Boyne Valley (Brú na Bóinne) National Park.

A cultural and natural heritage site of national and international importance, the demesne includes Dowth Hall, an eighteenth-century neoclassical country house, and Netterville Manor, a late Victorian almshouse. The lands amount to approximately one-third of the total area of the UNESCO World Heritage Property of Brú na Bóinne, which includes the great Neolithic passage tombs of Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth.

The purchase paves the way for the establishment Ireland’s seventh National Park. It is the second National Park to be established in the east of the country alongside Wicklow Mountains National Park.

Grey Partridge. Photo: Colum Clarke.

Dowth has been actively managed by Devenish Nutrition over the last decade to preserve its cultural heritage and biodiversity. As well as their position within the Brú na Bóinne World Heritage Property, the Dowth lands are important places for nature. They host a wide range of habitats, including species-rich grasslands, native woodlands and mature hedgerows. The Boyne River which runs through the lands is designated as a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) under the Habitats Directive, and as a Special Protection Area (SPA) under the Birds Directive. Following the State purchase, the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) will maintain the careful management of the farmlands, habitats and species to date and will work to protect and improve it even further. The new Boyne Valley (Brú na Bóinne) National Park is rich in bird life. 54 species of birds have been recorded at the site including Red-listed species of conservation concern such as Grey Partridge, Woodcock, Kestrel, Swift and Yellowhammer. 19 species recorded at the site are on the Amber list, including Kingfisher, Common Sandpiper, Cormorant and Little Grebe. Dowth is also a haven for other wildlife and plants. The River Boyne is of national importance for a number of species of bat including Common Pipistrelle, Soprano Pipistrelle, Natterer's Bat, Brown Long-eared Bat, Leisler’s Bat, Whiskered Bat, Daubenton’s bat and Nathusius’ Pipistrelle. It also hosts many species of butterfly including Small Tortoiseshell, Ringlet, Holly Blue, Peacock, Meadow Brown, Speckled Wood, Large White, Green-veined White, Small White, Red Admiral and Painted Lady. While surveys have not been completed, it is likely that a large population of macro-moths (of which there are over 800 species) occur within managed habitats. Seven species of bee have also been recorded here including White-tailed Bumblebee, Honey Bee, Common Carder Bee, Garden Bumblebee, Early Bumblebee, Red-tailed Bumblebee and Buff-tailed Bumblebee.

Woodcock on the nest. Photo: Richard T Mills

Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage, Darragh O’Brien TD welcomed the significant purchase and highlighted the many opportunities it could bring. “Rarely does the State get an opportunity to acquire lands of such significance. This landscape and property is of exceptional heritage importance. Here in this one place, we have over 5000 years of recorded history. In our care, it will significantly enhance our management of the Brú na Bóinne World Heritage landscape. We will conserve and protect Dowth’s heritage in line with our obligations to UNESCO and we will enhance responsible tourism, ensuring it becomes a standout destination. This purchase opens up possibilities for us to develop heritage partnerships, protect remarkable heritage and make it accessible. It is simply an outstanding opportunity for an outstanding place.” Minister of State with responsibility for Heritage and Electoral Reform, Malcolm Noonan TD said that the purchase represented an “outstanding addition to Ireland’s family of National Parks”. “We look forward to sustaining and growing this legacy to ensure that farming, nature and the cultural heritage of this ancient landscape can continue in harmony, as they have done since our ancestors first settled in the Boyne Valley over 5,500 years ago. Through our partnerships with state agencies, departments, local authorities and communities – which are enshrined in Heritage Ireland 2030, our national heritage plan – we are committed to nurturing Dowth as a key pillar of Ireland’s remarkable heritage that we can all admire, be proud of and enjoy.” The National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), the National Monuments Service and the Office of Public Works (OPW) will now work together to deliver a Masterplan for the property that allows for the protection, presentation and management of this area of the Boyne Valley. Management of Dowth Hall and lands will form part of the existing Brú na Bóinne Management Plan and strengthen the vision for the protection of Dowth’s remarkable heritage, including the Neolithic passage tomb discovered in 2017 under Dowth Hall itself. “The work begins now of developing a Masterplan for Dowth. We will approach this with a keen sense of responsibility, ambition and excitement, knowing that this is a remarkable opportunity for Ireland’s heritage to play a lead role in the regional economy and in place-making for the east of the country,” said Niall O Donnchu, Director General of National Parks and Wildlife Service. “This new National Park is a special place where history, heritage, nature and culture collide. We will work with stakeholders in developing a Masterplan that will deliver on its full potential for locals, visitors and generations to come. I want to pay tribute to our team across the National Parks and Wildlife Service and the National Monuments Services for their work on this acquisition, and on their readiness to take over custodianship of this remarkable place from Devenish who have championed and maintained it with such care over the last 16 years.”

New analysis charts fortunes of wintering waterbirds at a hundred Irish wetlands

The fortunes of Ireland’s wintering waterbird species have been published for 97 lakes, rivers and coastal estuaries across Ireland. You can now see how different species of ducks, waders and other waterbirds are faring at your local wetland, and how that compares to the national trend.

Every winter, hundreds of dedicated bird surveyors count the waterbirds in their locality as part of the Irish Wetland Bird Survey (I-WeBS). The survey,which has been running since 1994, is funded by the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) and coordinated by BirdWatch Ireland. The winter months see hundreds of thousands of swans, geese, ducks, waders and other waterbirds come to Ireland to escape the freezing conditions in their Arctic breeding grounds. As a result, Irish wetlands are of international importance for a number of species.

Over a thousand birdwatchers have contributed to I-WeBS since it began in winter 1994/95.

This study focused on 36 wintering waterbird species at 97 of the most closely-monitored wetland sites, spanning 15 counties across Ireland. The extent of increase or decrease for each species at each site was determined. Updated national trends were also produced. While national trends are produced at regular intervals, this is the first time that species trends for individual wetland sites have been published in this way. This information can now be used to better target conservation actions in particular counties and at specific locations and help ensure potential new developments don’t worsen the situation for wildlife in these vitally important areas.The full results of this ‘Waterbird Site Trends’ analysis can be viewed here, including links to view species trends at individual sites.

The new national trends for our wintering waterbirds can be viewed here.

Declines The greatest declines were seen in diving duck species, namely Goldeneye, Pochard and Scaup, which dropped by 65-90% on average since the mid-1990’s, across the 97 sites analysed. Climate change and warming winter temperatures are undoubtedly one of the drivers of these declines, allowing these birds to spend the winter closer to their breeding grounds in northern Europe. At a more local level in Ireland, loss of habitat, changes to water quality, increased disturbance on lakes and in estuaries, and poorly situated developments all worsen the situation, meaning fewer and fewer of these birds return to us each year. Wading birds of the Plover family have also undergone huge declines of over 50%. Lapwing, traditionally referred to as the ‘Green Plover’ or Pilibín and often considered Ireland’s national bird, declined by 64% since the mid-1990’s. Their close relative the Golden Plover, which feeds on grasslands in every county in Ireland in the winter, have declined by a similar amount, as have their rarer coastal relative the Grey Plover. Ireland’s breeding Curlew population is well known to be teetering on the edge of extinction, with only around 100 pairs nesting here in recent summers. Our wintering population is much larger though, as Curlew from northern Europe migrate to Ireland from late summer to early spring, but these birds face similar threats throughout their range. Our wintering Curlew have declined by 43% since the mid-1990’s.

Goldeneye - a diving duck species that has undergone large declines in Ireland.

Health Check “We regularly do this sort of analysis at national level, providing a ‘health check’ to see how Ireland’s wintering waterbirds are doing”, said John Kennedy of BirdWatch Ireland, who led this research “but now we’re delving a bit deeper to see precisely where the problems are. Some species will be showing the same upward or downward trend wherever you look, but there are some wetlands where we see faster declines than we’d expect. That might be because of particular problems at key sites – loss of habitats, changes to water quality, increased disturbance from recreational activities, and similar issues. Equally, there are likely to be places where a species is bucking the national trend and doing very well, and there will be practical lessons to be learned there too.”

Lapwing is considered by many to be Ireland's national bird, but their declines are cause for concern.

Increases Black-tailed Godwit, a member of the same family as the Curlew that breeds in Iceland, has increased by 92% since annual monitoring began in 1994. Species such as Mute Swan, Little Grebe and Grey Heron, which breed on Irish lakes and rivers are all stable or increasing in number. One of Ireland’s most recent arrivals, the Little Egret, has shown a steady and significant increase since it arrived into Ireland 20 years ago and is now widespread across the entire country. Species with a mixed report card include the Light-bellied Brent Goose, which has increased overall but is now showing a recent decline. Numbers of Sanderling, which the Pixar short movie ‘Piper’ was based on, are 85% higher than they were when monitoring began, but have decreased by 24% in the last five years. Recent declines of this magnitude are cause for concern and there is a risk that longer term increases for some species could be quickly undone in a few short years.

Sanderling have increased overall since monitoring began here, but shown recent declines.

“Ireland’s waterbirds are indicators of the health of the wetland environment they use. These are sites that we depend on too – for drinking water, flood relief, agriculture, tourism, aquaculture and industry. As is always the case with this sort of research, it has answered some questions but poses many more, and we’ll be scrutinising these results in the months and years to come to decipher some patterns of change that might not be so immediately obvious.” Said John Kennedy. Scientific Officer Brian Burke said “We would encourage everyone to visit the website and take a look at how the birds are faring at their local site, and other sites in their county. When you see the numbers side-by-side with the national trend figures, you might be surprised to see how a species is faring closer to home. Of course, the next step is to ensure that these data are used by communities, local authorities and politicians, to protect our precious wetlands and all of the ecosystem benefits they’ve brought us for generations. Since the survey began in 1994, over 1,100 counters from across the country have given up their time to provide this data, amounting to more than 81,000 winter site visits. None of this would be possible without their dedication!”

Grey Plover, a strictly coastal version of the more widespread Golden Plover and Lapwing, are faring poorly.

The results are also important in a planning context. I-WeBS Project Manager Lesley Lewis explains “An Appropriate Assessment (AA) is an assessment of the potential adverse effects of a plan or project (in combination with other plans or projects) on Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas, the latter often designated for migratory wintering waterbirds. These new site trends will therefore allow those completing AA to assess the current status of the waterbird species at the relevant sites. This is an important improvement to the process that will have implications for future developments across the country.” Dr Seán Kelly, waterbird ecologist at the NPWS who manages the I-WeBS contract added: “The Irish Wetland Bird Survey is an incredibly successful and valuable bird monitoring programme. The success of the programme is down to the hundreds of citizen scientists and NPWS and BirdWatch Ireland staff across Ireland who take part in the survey. The size, strength and extent of this bird monitoring community is simply fantastic, and I would like to thank every individual for their ongoing efforts. The survey has been running since 1994 so the resulting long-term dataset allows us to robustly monitor environmental change as it manifests in and impacts upon bird populations. I really encourage everyone to take a look at the report and consider the findings, at a local and national level. The data gathered under this survey allows us to further understand how and where conservation management and policies can be improved.”

The new national trends for our wintering waterbirds can be viewed here.

Full details about the Irish Wetland Bird Survey can be found here.