Turnstone

| Irish Name: | Piardálaí trá |

| Scientific name: | Arenaria interpres |

| Bird Family: | Waders |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

Winter visitor from northeast Canada and northern Greenland, occurs late July to late April.

Identification

The wader most likely to be found along our rocky shoreline. Mainly a winter visitor, but good numbers pass through Ireland in spring and autumn en route to/from arctic and subarctic breeding grounds. About the size of a Starling, with a stocky build and short orange legs. In winter, its dark brown upperparts, white underside and black breast crescent make it difficult to see amongst seaweed. Spring birds are brighter and show rich chestnut markings on the wing and back. In flight, Turnstones show a series of black and white stripes, resembling a miniature Oystercatcher. Usually occurs in small flocks, moving with head down, constantly flicking over seaweed fronds, pebbles and beach debris with its short, stubby bill, in search of sand hoppers and other invertebrates.

Voice

Often calls in flight - an abrupt, loud, bubbly "tutt-tutt-tutt…".

Diet

Sandhoppers & other marine invertebrates. Also fish carrion washed up on shore.

Breeding

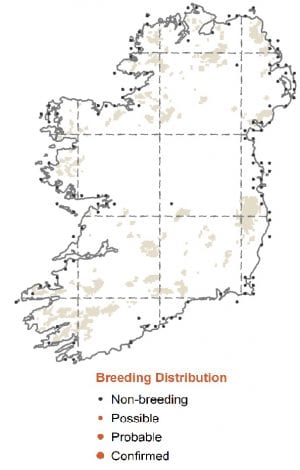

Does not breed in Ireland - breeding range all around shores of Scandinavia and Canada. Small numbers of non-breeding Turnstones (mainly first-summers) can be seen through the summer months.

Wintering

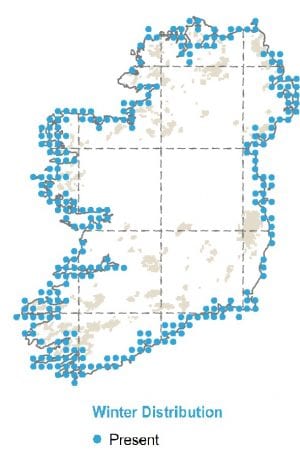

Winters all around the Irish coast.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

A Summer evening on Sandymount Strand

Over the summer we have been working in Dublin Port on our tern conservation project, funded by the Dublin Port Company. This project focuses on the Common and Arctic tern populations that breed within the Port area. Both Common and Arctic Terns are ‘Amber- listed’ species in Ireland - meaning they are of ‘medium conservation concern’ - and the colony that nests within Dublin Port is the third largest in the Republic of Ireland.

Terns have the longest migration of any animal. Arctic Terns, as their name might suggest, have a breeding range that extends up to the Arctic circle during our summer, before migrating down to their feeding grounds in Antarctica during our winter. Though Common Terns don’t migrate as far as this, with Irish- breeding Common Terns migrating down as far as the west coast of Africa during our winter, it is still an impressive distance to travel for a bird that doesn’t weigh much more than 100g.

Part of the work we do to monitor and protect terns in the port involves the ringing of chicks and adults,. This is when we add uniquely coded metal and colour ID rings to individual birds so that we can identify them. This work helps us to assess survival rates, site fidelity (i.e. do individuals return to the same place to breed every year, or do they move elsewhere), as well as to identify migration routes when birds are resighted travelling to and from their breeding grounds.

(Above: Arctic Tern fitted with metal and colour ID rings, under BTO and NPWS licence)

Over the summer, most of our ringing work has focused on tern chicks - if you follow us on social media, you may already have seen some of our posts relating to this (and if you haven’t, go ahead and give us a follow to keep updated on our important information, including many cute pictures of birds – links at the bottom of this article). However, as summer draws to an end, and the chicks start to fledge and join the adults to begin their long migration south, we change tactics with the aim of capturing adults rather than chicks. To do this, we set up mist nests near their evening roost sites. You can see how this looks in the photos below (just!!). It’s a task easier said than done. It requires the right tides to align with the right time and because of this we usually only get one opportunity a year to ring adult and fledgling terns in this way, so it is an exciting opportunity whenever it arises. And luckily, this year did not disappoint!

(Above 1 & 2, the team setting up the mist nets in the fading light over Dublin Bay)

We caught not only terns, but also Oystercatchers, Redshanks, Turnstones and even a Black-tailed Godwit! With over 60 birds captured, we caught more birds this year than in the previous five put together. A fantastic day for us which offers us an opportunity to learn much more about these birds in the years to come. And while that will be the last of the terns we catch this summer as they migrate away, it will hopefully be the first of the waders as they make their way to overwinter in Ireland.

(Above: a night vision scope used to see when a bird has been caught in the net)

The highlights of this mammoth haul include; a Common Tern that was ringed in Senegal whilst migrating northwards in the spring, offering us an insight into the migration paths that our Common Terns take; and we had a resighting of a Common Tern that was ringed in 2010., For a species that lives on average to around 10 years old, a resighting of a 15-year-old is pretty special; we colour- ringed three Turnstones, which is part of a new project on this species and so we are delighted to be able to ring these for the first time; and we also had a resighting of an Oystercatcher, which helps build our knowledge on the site fidelity of this species and their migration routes between their summer breeding and winter feeding grounds. All in all, it was a great night s outing for us and we will be keeping everything crossed for the same again next year! Until then, follow us on Facebook, Instagram and X for updates on all of our ongoing work. If you would like to support us and to make a direct contribution to the protection of Ireland’s birds and biodiversity, please do so by becoming a member here and signing up for our members only newsletter, Wings, alongside many more members only benefits.

(Above: Redshank fitted with metal and colour ID rings)

All photos taken under NPWS license and all handling and ringing is done by trained and licensed bird ringers. The Dublin Bay Birds Project is funded by

Extinction of Slender-billed Curlew must be a wake-up call for global biodiversity action

In recent days, scientists sounded the death knell for Slender-billed Curlew, declaring the migratory shorebird globally extinct.

Published in IBIS, the International Journal of Avian Science, the analysis of the Slender-billed Curlew’s conservation status was a collaboration between RSPB, BirdLife International, Naturalis Biodiversity Centre and the Natural History Museum.

This is the first known global bird extinction from mainland Europe, North Africa and West Asia and, unless biodiversity loss is treated as the crisis that it is, it won’t be the last.

Indeed, the extinction of the Slender-billed Curlew should serve as a wake-up call to protect other vulnerable species from a similar fate.