Back in 2009, there was nowhere to hide for the European Commission. The state of EU fisheries at this time was characterised by “overfishing, fleet overcapacity, heavy subsidises, low economic resilience and decline in the volume of fish caught by European fishermen.” In order to turn the ship around, the EU Common Fisheries Policy reforms in 2013, concluded that overfishing must end, and a hard-legal deadline was set for 2020. Despite expectations of this significant change, EU Fisheries Ministers and the European Commission have still held their December fisheries negotiations in Brussels behind closed doors. Following these ‘dark days’ behind closed doors, came public announcements that they had sanctioned overfishing in the North East Atlantic for another year (despite the 2020 legal deadline).

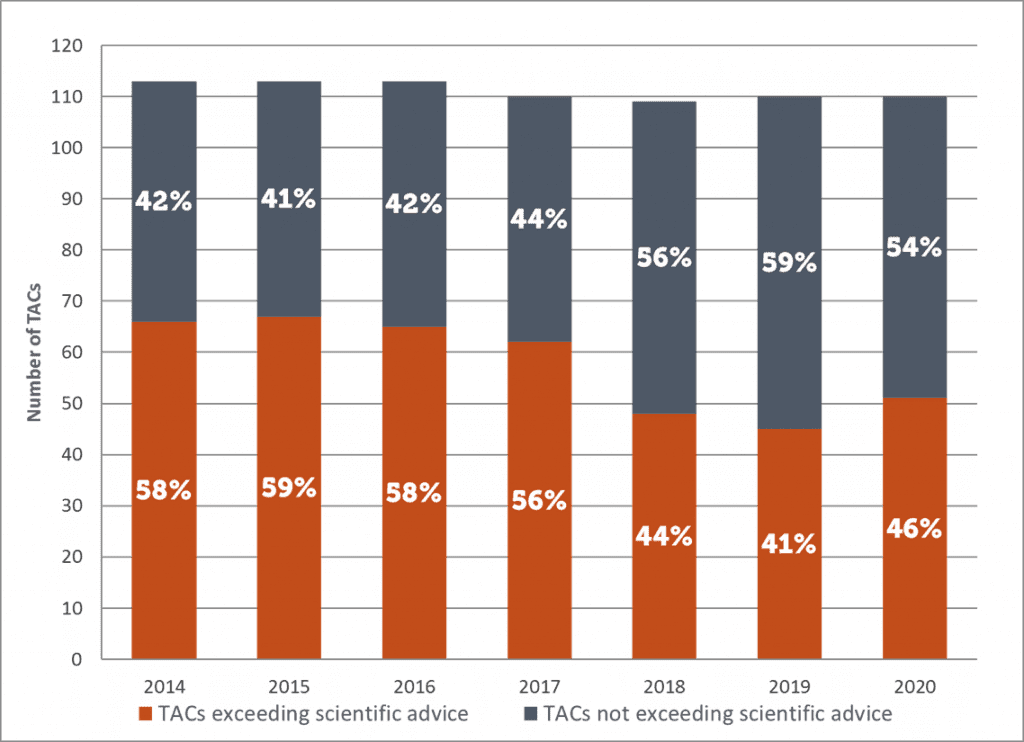

According to Pew Trusts, 46% (51 of 110) of the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) limits, agreed in Brussels for 2020, exceeded the best available scientific advice. Not only did the EU fail to make the significant progress needed, they even went backwards exceeding the number of TACs set above scientific advice in both 2018 and 2019. More alarming still, Pew Trusts conclude that even these figures are likely an underestimate of the actual true scale of overfishing, and that an ongoing lack of transparency around both the negotiations, and its outcomes, are ongoing impediments to sustainable fisheries management.

Figure 1: Comparison of north-east Atlantic TACs set by fisheries ministers exceeding or not exceeding the scientific advice on catch limits for 2014-20 (PEW Trusts)

Figure 1: Comparison of north-east Atlantic TACs set by fisheries ministers exceeding or not exceeding the scientific advice on catch limits for 2014-20 (PEW Trusts)

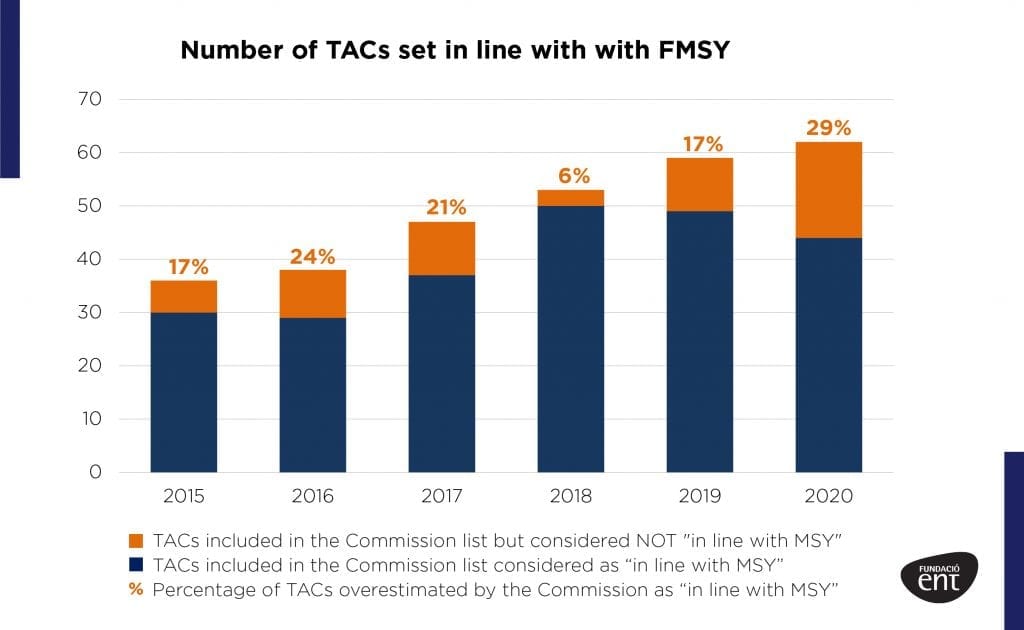

These concerns have been vindicated by a coalition of Spanish and Portuguese Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), including Fundació ENT, Sciaena and Ecologistas en Acción, who over the last 5 years have analysed the European Commission public reports on the progress that has been made towards ending overfishing. They have found that the European Commission have inflated figures for the number of TACs set in line with scientific advice, on average by 19% between 2015 to 2020, and by a whopping 29% for 2020. Consequently, it means that the overall number of TACs set in line with scientific advice for 2020, is just 44 (instead of 62).

Figure 2: Comparison of TACs included in the Commission list as beining “in line with MSY” (Fundació ENT).

It is not only NGO’s who have been coming forward to highlight the lack of transparency at the heart of EU fisheries governance. The European Ombudsman, Emily O’Reilly, whose office is an independent and impartial body tasked with holding the EU’s institutions and agencies to account, has gone as far as accusing the European Commission of ‘maladministration’ over their ongoing refusal to address the lack of transparency around the annual fisheries negotiations. O’Reilly went as far as to say, “the Council has failed fully to grasp the critical link between democracy and the transparency of decision-making regarding matters that have a significant impact on the wider public. This is all the more important when the decision-making relates to the protection of the environment.” Further, O’Reilly said that the European Council’s position was that “a key democratic standard – legislative transparency – must be sacrificed for what it considers to be the greater good of achieving a consensus on a political issue.”

For sure, transparency and accountability in decision making are critical to democracy. The failure of the European Commission and European Council to adhere to its own laws is about more than whether or not progress is being made towards fisheries management. It raises serious concerns about the health of our democracy and the impunity with which the law can be cast aside in the interest of political convenience. Its time to blow the doors off behind closed-door negotiations and bring EU fisheries negotiations out into the light. For the sake of the future sustainability of our seas, fishing communities and our democracy, it is clear that we cannot wait any longer.

Fintan Kelly,

Policy Officer,

BirdWatch Ireland