Hen Harrier

| Irish Name: | Cromán na gCearc |

| Scientific name: | Circus cyaneus |

| Bird Family: | Raptors |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

Breeds in the uplands and bogs of Ireland.

Identification

Size between Montagu's Harrier and the larger Marsh Harrier. Females and juveniles similar - brown with white rump and dark rings on the tail, hence often referred to collectively as 'ringtails'. Females are bigger than males. Males very distinctive, appearing strikingly pale below, with blue grey upper parts and jet black wing-tips. Hen Harriers have somewhat of an owl-like face, particularly accentuated in female birds.

Voice

Usually only heard in the breeding season near the nest site. Quick, chattering calls in alarm and display and whistling calls from female to male, when receiving food.

Diet

Small birds and mammals, which are caught by surprise. Will sometimes use cover, such as woodland edges and bushes, to surprise prey.

Breeding

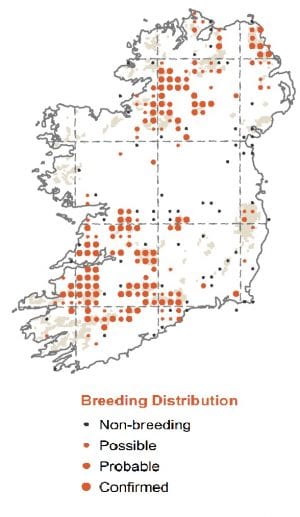

Breeding birds are confined largely to heather moorland and young forestry plantations, where they nest on the ground. Hen Harriers are found mainly in Counties Laois, Tipperary, Cork, Clare, Limerick, Galway, Monaghan, Cavan, Leitrim, Donegal and Kerry. The species has declined, probably due to the loss of quality moorland habitat due to agricultural changes, and maturing forest plantations. Hen Harriers mainly hunt over moorland whilst breeding where they take small ground nesting birds and mammals.

Wintering

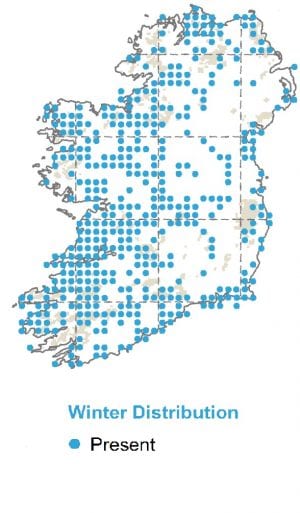

Spends winter in more coastal and lowland areas throughout Ireland hence most easily seen on the coast in the winter months. Good sites include the North Slob Nature Reserve and Tacumshin Lake in County Wexford, as well as the East Coast Nature Reserve in Co. Wicklow.

Monitored by

BirdTrack and the Hen Harrier Roost Survey.

Blog posts about this bird

BirdWatch Ireland welcomes the scrapping of the winter stubble rule

BirdWatch Ireland is pleased that the rule for shallow cultivation of winter stubbles has been scrapped in the latest iteration of the Nitrates Action Programme. It is regrettable, however, that this decision was not made sooner, and particularly before farmers cultivated stubble grounds in 2025, leaving threatened bird species looking for other food supplies this winter. In the medium and long term, Ireland’s Common Agriculture Policy Strategic Plan and National Restoration Plan must incentivise farmers to provide sufficient quantity and quality of habitats to restore both wintering and breeding farmland bird populations.

The controversial winter stubble rule was introduced in 2022, despite vociferous opposition from BirdWatch Ireland on account of the risk of severe impacts to farmland birds over the winter months, when food supplies for many Red- and Amber-Listed Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland are in short supply.

The stubble fields left after crops have been harvested often harbour spilled seeds, which seed-eating birds, such as the Yellowhammer and the Skylark, and rodents will consume during the cold winter. These small birds and mammals are prey species for other birds, including the Hen Harrier, a highly protected and increasingly rare bird of prey that is experiencing ongoing declines. In our submission to government at that time, we highlighted that 30 Red- or Amber-Listed Birds of Conservation in Ireland relied on winter stubbles for food.

Extinction of Slender-billed Curlew must be a wake-up call for global biodiversity action

In recent days, scientists sounded the death knell for Slender-billed Curlew, declaring the migratory shorebird globally extinct.

Published in IBIS, the International Journal of Avian Science, the analysis of the Slender-billed Curlew’s conservation status was a collaboration between RSPB, BirdLife International, Naturalis Biodiversity Centre and the Natural History Museum.

This is the first known global bird extinction from mainland Europe, North Africa and West Asia and, unless biodiversity loss is treated as the crisis that it is, it won’t be the last.

Indeed, the extinction of the Slender-billed Curlew should serve as a wake-up call to protect other vulnerable species from a similar fate.