Corncrake

| Irish Name: | Traonach |

| Scientific name: | Crex crex |

| Bird Family: | Crakes & Rails |

red

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

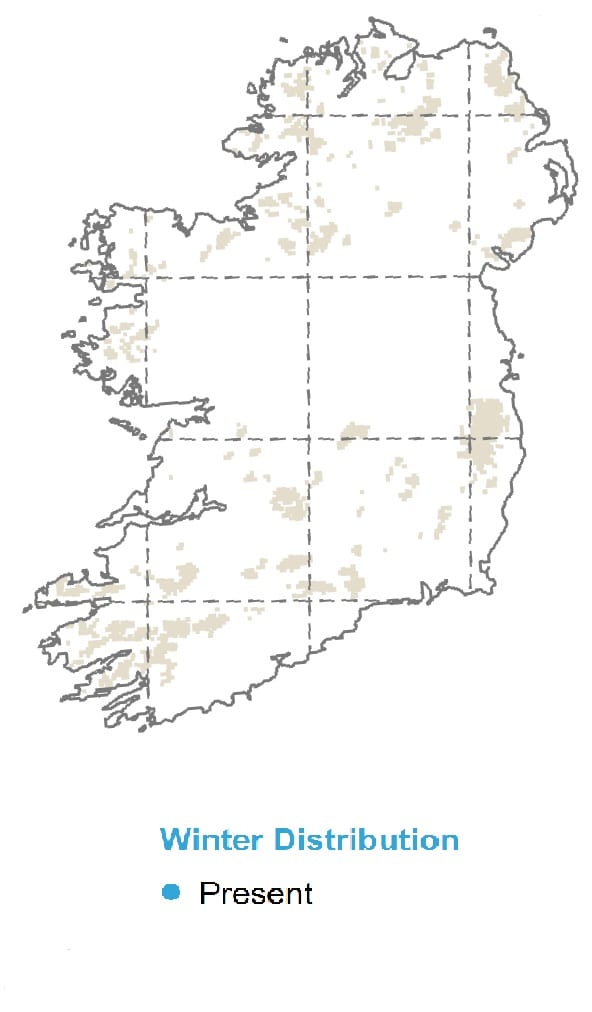

Summer visitor from April to September.

Identification

A shy, secretive bird of hay meadows. The distinctive kerrx-kerrx call of the male often being the only indication of their presence. Adults show a brown, streaked crown with blue-grey cheeks and chestnut eye-stripe. Breast buffish grey with chestnut smudges on breast sides. Flanks show chestnut, white and thick black barring, fading on undertail. Wings bright chestnut, striking in flight. Short bill and yellow-brown legs. Prefers to run through thick cover, dropping quickly back into cover when flushed. Flight is weak and floppy. Large bright chestnut patches on wings and dangling legs are distinctive in flight

Voice

Males give a very loud, distinctive kerrx-kerrx call during the breeding season, which is repeated during the day in fits and starts, reaches a peak about dusk and continuing through the night till dawn. Its onomatopoeic Latin name seems to be derived from this sound

Diet

Corncrakes eat about four-fifths animal food and one-fifth vegetable matter. The animal part consists mainly of insects, but slugs, snails and earthworms are also eaten. Plant material taken includes seeds of grasses and sedges, eaten in larger quantities in the autumn.

Breeding

Breeding is from mid May to early August. Nests on the ground in tall vegetation. Most nests are in hay fields. The greenish-grey mottled eggs hatch after seventeen days of incubation. For the first four days after hatching the chicks are fed by their mother. They then learn rapidly to feed themselves. Flight takes place in a little over thirty days. Females have two broods, the first hatching in mid June and the second one in late July to early August. There can be as little as two weeks between the chicks fledging from the first brood to laying a second clutch.

Monitored by

Major annual conservation measures to protect this endangered species.

Blog posts about this bird

Key Insights from the EPA's eighth 'State of the Environment' Report

By Rosalind Skillen

The eighth ‘Ireland: State of the Environment’ Report has been published by the EPA. It provides a comprehensive assessment of the Irish environment, examining key themes such as air quality, climate change, water quality, the marine environment, land use, biodiversity, and the circular economy. The report further examines how these environmental challenges are linked to human health and well-being, and the need for greater investment in infrastructure, a just transition, and systemic change to achieve a sustainable future for Ireland.

Nature

Nature, wildlife, and how they relate to our society, sense of place and health, are recurrent themes in the report. Chapter 7 looks specifically at the crucial roles of nature and biodiversity in Ireland, detailing how the environment provides vital ecosystem services for humans, including clean air and water, food, raw materials and recreational opportunities.

The chapter underscores the alarming rate of biodiversity loss occurring globally and nationally, with estimates suggesting that up to a million species are facing extinction. Ireland falls below the EU average in terms of habitats in 'good' conservation status. Many of the few remaining natural and semi-natural habitats are in a poor or bad state. 85% of our protected habitats and almost one-third of our protected species of flora and fauna are in unfavourable status, over half our native plant species are in decline and more than 50 bird species are of high conservation concern.

Human activities are identified as the primary driver of this decline, with a staggering 83% reduction in wild animal populations since the beginning of civilization. This loss of nature and biodiversity is so severe that it could signal a sixth global mass extinction event.

Birds

The work of BirdWatch Ireland and colleagues in the RSPB in Northern Ireland on the Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland assessment (BoCCI) receives significant attention in the report as respected source of information on the status of regularly occurring birds in Ireland. The latest BoCCI report placed 26% of the 211 species assessed on the Red List, meaning that they are of high conservation concern. Particularly affected are breeding waders, and birds that use upland and farmland habitats. Further, some of the most iconic bird species, including the Curlew, Corncrake and Hen Harrier, are considered to be on the brink of extinction. There has been a 59% decline in the Hen Harrier population since 2000, and a 98% decline in the curlew population since the 1980s. The species has declined by a third in the ten years that it took government to prepare a ‘threat response plan’ for this magnificent bird of prey. The published plan is weak and of serious concern to BirdWatch Ireland.

The next State report to the European Commission on the assessment of the conservation status of protected birds (Article 12) in Ireland is due in 2025.

Hen Harrier. Photo: David Leckie.

Threats Threats to nature, wild birds and biodiversity in Ireland include changes in land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution, and invasive alien species. Agricultural intensification has had a significant impact on farmland birds through habitat loss and fragmentation and changes in practices. Water pollution is driven by increased nutrients making their way into waterways from agriculture, wastewater treatment plants, septic tanks and forestry, and result in changes to conditions for waterbirds and river birds. Afforestation is a significant threat to birds of open country like Hen Harrier, Curlew and more. Ireland’s most recent formal NPWS report on the condition of our protected habitats and species outlined that 85% of our protected habitats were at unfavourable conservation status, almost half of which show ongoing declines, including marine, peatland, grassland and woodland habitats. The over-exploitation of peatlands, in particular, is discussed in the SOER. Peatlands continue to be drained, overgrazed, and burnt for fuel, impacting biodiversity. The importance of protecting and restoring Ireland's remaining peatlands is emphasized, recognizing their value for biodiversity, carbon storage, and flood mitigation. When it comes to the marine environment, the over-exploitation of marine fish stocks as a significant driver of biodiversity loss. Declines in commercial fish stocks are linked to over-fishing and the impact of climate change on biodiversity is also discussed. Rising temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns can affect species distribution and habitat suitability, leading to shifts in populations and potential extinctions. Urgent action needed The declaration of a national biodiversity emergency in Ireland by Dail Éireann in 2019 was a pivotal moment, leading to the establishment of national Citizens' Assembly on Biodiversity Loss. However, while the policy landscape has evolved since the declaration of a biodiversity emergency in Ireland, the EPA report makes clear there remains an urgent need for tangible action and evidence-based results to address the challenges facing biodiversity in Ireland. For instance, measuring and assessing the state of biodiversity using appropriate indicators would help to evaluate the effectiveness of conservation efforts and to inform policy decisions. The EPA does outline the positive actions that are happening but there is a real need for scaled up action and investment in the delivery of further actions. Ireland’s Nature Restoration Plan will be very significant in this regard as it sets out to restore 20% of land and sea by 2030 and all habitats by 2050 which is very ambitious.

Corncrake. Photo: Colum Clarke.

In conclusion Overall, the EPA State of the Environment report paints a stark picture of the state of nature and biodiversity in Ireland, highlighting the significant threats they face and the urgent need for effective conservation and restoration efforts. While some positive signs are acknowledged, a 'business-as-usual' approach is not sustainable and will lead to further decline. The progress made over the past four years will need turbocharged if we are to make good of Ireland's environmental goals and its commitments to international agreements. Ireland’s Nature Restoration Plan will be very significant in this regard as it sets out to restore 20% of land and sea by 2030 and all habitats by 2050 which is very ambitious and needs to be matched by significant investment and communication of the benefits to all of society.

Positive news for Ireland's Corncrake population but numbers remain critically low

BirdWatch Ireland welcomes the news that Ireland’s Corncrake population is on the rise but says that cautious optimism is required as numbers still remain critically low.

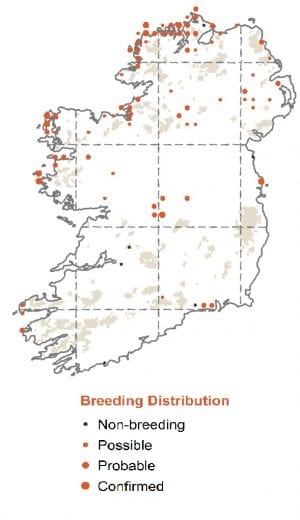

Data released by the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) on Wednesday showed that numbers of Corncrakes recorded in the core breeding areas of Donegal, Mayo and Galway have increased since 2022. Additionally, the survey data notes the first confirmed sighting of a Corncrake on the Aran Islands for 25 years.

A total of 218 Corncrake breeding territories were recorded in 2023, up by 10 per cent on 2022 and exceeding 200 for the first time in a decade.

Since 2021, the Corncrake/Traonach LIFE Project – a five-year project funded through the EU and co-ordinated by the NPWS – has been working on a number of measures aimed at preventing the further decline of the Corncrake. Data about the Corncrake population in Ireland is gathered on an annual basis.

BirdWatch Ireland welcomes the positive news for Corncrakes in Ireland. Through schemes implemented by Corncrake Life, farmers and landowners in the core breeding areas of Donegal, Mayo and Galway are managing 1,500 hectares of land for corncrakes. This includes just under 10ha of land owned by BirdWatch Ireland at our reserve at Termoncarragh, Co. Mayo, where four calling males were recorded this summer. With the numbers rising from a very low baseline, the organisation said there is a dire need for such conservation efforts to be continued and expanded upon if we are to bring the species back from the brink of extinction in Ireland.

The Corncrake is a red-listed species that has suffered drastic population declines in recent decades. Once a common summer visitor whose distinctive “kerrx-kerrx” call was heard across Ireland, it is now confined to small parts of Donegal and Western parts of Connaught. Their population decline is largely due to the advent of intensive farming practices, particularly the conversion of hay meadows to multiple cut silage and loss of marginal vegetation which would have provided cover for the birds on their first arrival in spring. Corncrakes are now confined to areas where traditional farming methods are still utilised.

BirdWatch Ireland staff are involved in Corncrake conservation measures including habitat management on Tory Island off the coast of Co Donegal and on our Termoncarragh Reserve in Co Mayo. This involves working very closely with local farmers and landowners, who play a crucial role in this vital work.

Members of the public also play a vital role in Corncrake conservation as they are our eyes and ears around the country. Corncrakes are nearing the end of their breeding season for this year so hearing the distinctive call would be unusual. However, if you have been fortunate enough to see or hear a Corncrake, we would ask you please to report it, along with as much information as you can about the location, habitat, appearance, sound and behaviour of the bird, via the Corncrake Life website. This will help to provide much-needed information on these scarce birds and will aid efforts to conserve this species in Ireland.