Lapwing

| Irish Name: | Pilibín |

| Scientific name: | Vanellus vanellus |

| Bird Family: | Waders |

red

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

Residents, summer visitors from the Continent (France & Iberia) and winter visitors (from western & central Europe). Some overlap between all three groups. Greatest numbers occur in Ireland between September & April

Identification

Distinct black-and-white, pigeon-sized wader, with wide rounded wings and floppy beats in flight. Wispy crest extending upwards from back of head and green/purple irridescence seen at close range. Pinkish legs.

Voice

Plaintive "pwaay-eech' in flight, song described as 'chae-widdlewip, i-wip i-wip… cheee-o-wip'

Diet

Feed on a variety of soil and surface-living invertebrates, particularly small arthropods and earthworms. Also feed at night, possibly to avoid kleptoparasitic attacks by Black-headed Gulls, but also, some of the larger earthworm species are present near the soil surface at night, and thus are more easily accessible. They use traditional feeding areas, are opportunistic, and will readily exploit temporary food sources, such as ploughed fields and on the edge of floodwaters.

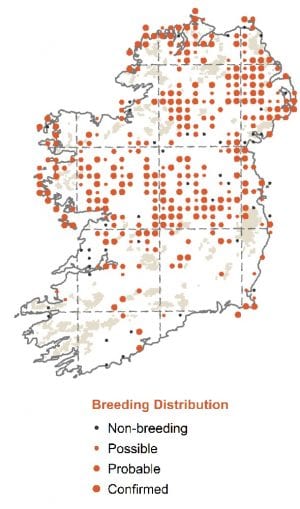

Breeding

They breed on open farmland, and appear to prefer nesting in fields that are relatively bare (particularly when cultivated in the spring) and adjacent to grass.

Wintering

Wintering distribution in Ireland is widespread. Large flocks regularly recorded in a variety of habitats, including most of the major wetlands, pasture and rough land adjacent to bogs.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

Curlew EIP harnesses people-power to help stem population declines

The Irish Breeding Curlew European Innovation Project (EIP) may be wrapped up and the final report written, but its impact is sure to be felt for years to come.

A multi-partnership project involving BirdWatch Ireland, the Irish Natura and Hill Farmers Association (INHFA), the Irish Grey Partridge Conservation Trust and Teagasc, the Curlew EIP looked to address factors contributing to the decline of breeding Curlew in Ireland. Working closely with the farming community in South Leitrim and South Lough Corrib, the project developed and trialled new and innovative approaches to help stem the decline of Ireland’s breeding Curlew population.

Predation of nests and chicks is also known to be one of the main reasons for the decline of Curlew populations. To address this The Curlew EIP developed “Conservation Keepering”, a tool which placed international best practice, ethics and standards in predator management at its core. It trialled the Conservation Keepering Option, an agri-environmental measure with 33 farmers over four years from 2020 to 2023. Through this innovative approach, farmers carried out predator management to reduce predator populations in and around important Curlew breeding sites during the breeding season, and provided landscape-level support to the project’s Conservation Keepers.

Predation of nests and chicks is also known to be one of the main reasons for the decline of Curlew populations. To address this The Curlew EIP developed “Conservation Keepering”, a tool which placed international best practice, ethics and standards in predator management at its core. It trialled the Conservation Keepering Option, an agri-environmental measure with 33 farmers over four years from 2020 to 2023. Through this innovative approach, farmers carried out predator management to reduce predator populations in and around important Curlew breeding sites during the breeding season, and provided landscape-level support to the project’s Conservation Keepers.

Innovative approaches

Breeding Curlew represent one of the highest conservation priorities in Ireland, with only 105 confirmed breeding pairs recorded during the 2021 National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) survey. This represents a 98% decline in breeding pairs in the Republic of Ireland since the 1980s. Habitat loss and degradation (as a result of agricultural intensification, land drainage and afforestation) has been identified as one of the primary threats to breeding Curlew populations in Europe and, though multi-faceted, addressing this was a key element of the Irish Breeding Curlew EIP. Over three years (2020 – 2022), 35 farmers trialled the “Curlew Habitat Option”– a results-based agri-environmental measure to manage Curlew breeding habitat that was supported with the provision of specialist advice and farmer training. Capital Works were also developed and trialled to support this measure and improve breeding habitat by, for example, removing scrub or creating chick feeding habitat. Participating farmers were financially rewarded for delivering high-quality Curlew breeding habitat, with payment levels linked to annual field scores. Breeding season sward height, wet features (suitable for chick feeding), scrub encroachment and predator habitat were some of the elements scored. Project results showed a highly significant statistical increase in field scores (and therefore habitat quality) on fields entered into the Curlew Habitat Option for at least two years, in both Leitrim and Lough Corrib. Farmer training and support was shown to be a key factor in the achievement of habitat improvements (and increasing field scores). In the first year of the scheme Covid-19 restrictions prevented farmer training from taking place, and 2020-2021 were the only years between which there was no significant increase in field scores. Predation of nests and chicks is also known to be one of the main reasons for the decline of Curlew populations. To address this The Curlew EIP developed “Conservation Keepering”, a tool which placed international best practice, ethics and standards in predator management at its core. It trialled the Conservation Keepering Option, an agri-environmental measure with 33 farmers over four years from 2020 to 2023. Through this innovative approach, farmers carried out predator management to reduce predator populations in and around important Curlew breeding sites during the breeding season, and provided landscape-level support to the project’s Conservation Keepers.

Predation of nests and chicks is also known to be one of the main reasons for the decline of Curlew populations. To address this The Curlew EIP developed “Conservation Keepering”, a tool which placed international best practice, ethics and standards in predator management at its core. It trialled the Conservation Keepering Option, an agri-environmental measure with 33 farmers over four years from 2020 to 2023. Through this innovative approach, farmers carried out predator management to reduce predator populations in and around important Curlew breeding sites during the breeding season, and provided landscape-level support to the project’s Conservation Keepers.

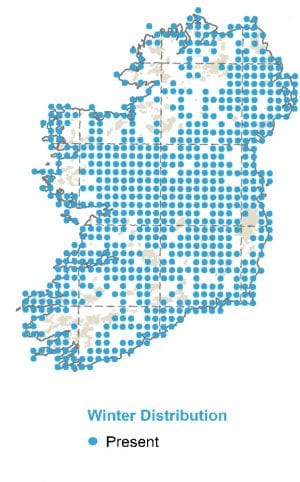

Results of the Curlew EIP

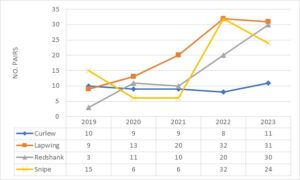

Curlew (and other breeding waders, where present) surveys were carried out between March and May annually to determine the number of confirmed, possible and probable breeding pairs, as well as breeding productivity (measured by the number of successfully fledged chicks). Populations in Corrib were stabilised over the lifetime of the project and showed some growth by 2023, increasing to 11 pairs.

Total no. of pairs, pairs confirmed breeding, hatching, and fledging by area and year.

Unfortunately, a complex range of factors led to a different outcome in South Leitrim. Leitrim had poor productivity in most years and consequently, populations showed continual decline. Predator pressure and fragmented habitat due to afforestation and scrub invasion around the bogs where Curlew were breeding were shown to be impacting on breeding success. Scrub and forestry are known to hold higher numbers of predators and lead to an increase in predation of breeding Curlew (and other ground-nesting birds) for up to a kilometre from the edge of the woodland. If local populations are to be saved in Leitrim, substantial efforts will need to be made to address these issues. As an umbrella species, measures carried out to protect breeding Curlew benefit other breeding waders. Populations of three other Red-listed species of Conservation Concern – Lapwing, Redshank and Snipe – all showed a marked increase since the project began, with total populations increasing by 215 % from 27 to 85 breeding pairs.Total number of pairs for all species, by year in the Corrib project area.

Satellite Tagging breeding Curlew

The project also carried out satellite tagging of breeding Curlew to learn about their habitat usage and home range during the breeding season. Adult (mainly male) Curlew were satellite tagged allowing project staff to locate their nest and erect predator-proof fences around them, and focus their habitat and predator management work. The project also collaborated with NPWS and pooled their data for analysis on the home range size needs of Ireland’s breeding Curlew. The results of this show that breeding Curlew need a minimum of a 2km radius free from afforestation around their nest sites. It is anticipated that this work will help influence Ireland's future afforestation policy. Through satellite tagging and colour-ringing, the project also identified new information on the behaviour of non-breeding birds, which were shown to hold territory and exhibit breeding calls. This was also found to be the case with other satellite projects across the UK and Europe and it is not fully known whether these are juvenile birds learning breeding behaviour, or birds that are attempting to breed, but who have not found a mate. Only two of the 12 birds caught and colour-ringed returned to the project area in subsequent years. It is thought that this is a result of high adult mortality in an ageing population. Look out for birds with blue and white colour rings above the knee joint, with an individual marker ring on the LA – yellow and beginning with the letter A.People Power

The measures in the Curlew EIP require a team of dedicated and engaged people to carry them out. The project’s success is directly linked to the farmers and landowners across Lough Corrib and South Leitrim, whose commitment to saving the biodiversity on their farms and in their local area was key to the project's success. The interest in nature amongst members of the farming community is unquestionable, but it is vital that this is met with support, both financial and advisory, if we are to help to reverse the decline of threatened farmland bird species.Looking forward

The Curlew EIP concluded in December 2023, with many of its measures adopted into ACRES Cooperation (CP) either directly or in a revised form. Work by the Curlew EIP and by BirdWatch Ireland using its hotspot mapping showed that many important areas for breeding Curlew and other waders were located outside of ACRES CP areas and was instrumental in securing the inclusion of a National Breeding Wader EIP and a Shannon Callows EIP in Ireland’s new agri-environmental programme under the Common Agricultural Plan (CAP). The National Breeding Wader EIP comes on stream in 2024 and will provide for breeding waders nationally going forward. The Irish Breeding Curlew EIP was funded by the Department of Agriculture Food and the Marine’s, European Innovation Partnership (EIP) fund. Read the full report here: The Irish Breeding Curlew EIP - End of Project Report March 2024

Nesting Season 101 – Hedge-cutting and the Law

Birds in Ireland are facing pressures from all sides, with habitat loss and fragmentation, predation, disturbance and climate change just some of the things they have to contend with. Nesting birds and their young are particularly vulnerable and, while it is vital that we don’t interfere with wild birds at this time, there are some things you can do to support birds during nesting season. One of the easiest ways to do so is to abide by existing laws around hedge-cutting and vegetation burning.

Hedge-cutting and vegetation burning ban

Under the Wildlife Act, it is against the law to cut, burn or otherwise destroy vegetation including hedges between March 1st and August 31st. The purpose of this ban is to prevent the disturbance and destruction of nesting sites of many of our wild bird species.Hedge-cutting

Hedges provide important nesting sites for many wild birds – including Robin, Wren, Blackbird, and Dunnock, to name a few – as well as a bounty of food for a variety of other species. They also offer shelter and safe routes for wildlife to travel along, known as wildlife corridors. Hedges offer numerous benefits to humans including food, natural property boundaries, shelter for crops and livestock, noise reduction and visual appeal. As healthy hedges also sequester and store atmospheric carbon, and help to slow water movement and prevent flooding, they are absolutely vital in mitigating the effects of climate change. While some green-fingered folk may argue that, with a steady hand, they can leave a nest unshaken, the sheer act of getting that close to the hedge and nests within it could be enough for the adult birds to abandon it. Without their parents, the eggs and chicks in the nest have virtually no hope of survival. If they don’t succumb to starvation due to lack of food delivery by an adult bird, they are likely to be victims of predation. 63% of regularly occurring Irish birds are of serious conservation concern, with 26% of them now Red-listed species of conservation concern and 37% Amber-listed species of conservation concern. With the decline in bird populations directly linked to the loss and degradation of habitat, it is important that we do all we can to preserve what remains. You can play your part in this by leaving your hedges alone during the nesting season, and by spreading the word to others.Wren. Photo: Michael Finn.

Vegetation Burning

The Wildlife Act also prohibits the burning of vegetation during the nesting season. This is aimed at protecting our ground-nesting bird species in upland habitats, many of which have seen their populations plummet in recent decades. This includes species such as Curlew, Lapwing, Skylark, Meadow Pipit and Hen Harrier. While burning is not the only cause of the decline of these species, it does pose a significant threat to their breeding success when carried out during the nesting period. But even during the 'open season' for burning, out-of-control fires, can have devastating consequences on habitats sometimes 'melting' peat soils due to the heat and destroying their functions as carbon stores and sinks as well as habitats for wildlife, for years. Illegal fires during the closed period can lead to the destruction of nests and young of these already vulnerable species, as well as the disturbance of breeding adults. Additionally, such burning can damage habitats that are protected in their own right such as Raised Bog and Blanket Bog. In addition to being unique and biodiverse habitats, our bogs serve as carbon sinks, meaning that they play a huge role in mitigating the effects of climate change.

Reporting illegal cutting and burning

Despite the ban on hedge-cutting between March 1st and August 31st, it is possible that you will come across cutting and burning during this period. Indeed, the Wildlife Act does have exemptions which allow hedge-cutting during the closed period, for example, should there be road safety concerns. In saying this, regardless of who is involved, don’t assume that those cutting the hedge have received the green light to do so. It may well be that they are breaking the law. If you witness hedge-cutting or burning in any place or at any time during this period, please report it to the local Gardaí and the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS). You can read the NPWS guidance on reporting Wildlife Crime here and find contact details for your local NPWS Wildlife Ranger here.Enforcement of the Wildlife Act

Efforts to tackle wildlife crime in Ireland have been strengthened in recent times. Forty-three prosecution cases were initiated by NPWS in 2023 for alleged breaches of wildlife legislation, a 39% increase since 2022. Wildlife crimes reported range from the disturbance of bats, illegal hunting, damage to Special Areas of Conservation (SACs), destruction of hedgerows and burning of vegetation within the restricted period, and more. This increase in action against wildlife crime is very much welcomed by us at BirdWatch Ireland. However, there is still work to be done. It is widely known that our wildlife legislation is not as strongly enforced as it could be, and that the initiation of cases and rates of conviction are higher in some locations than others. There are a number of reasons for this including a general lack of training and resources in the area of wildlife crime in both the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) and An Garda Siochána, and difficulty in gathering sufficient evidence on certain forms of wildlife crime. With this in mind, if you witness any other form of wildlife crime, or simply are worried about the situation for wildlife in this country, we would encourage you to also contact your local and national elected representatives to voice your concerns.