Swallow

| Irish Name: | Fáinleog |

| Scientific name: | Hirundo rustica |

| Bird Family: | Swallows & Martins |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

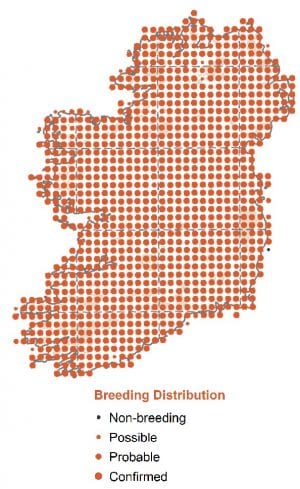

Common summer visitor throughout Ireland from mid-March to late-September.

Identification

A common and easy to see species. Adults are instantly recognisable by their glossy black wings and back, long tail streamers and contrasting white undersides. At close range, the red face-patch can be seen, as well as a narrow black breastband. In juveniles, the face-patch is a pale orange, while the tail streamers are appreciably shorter than on adults.

Voice

Very vocal. The song consisting of several musical twittering notes followed by a short buzz can be frequently heard. A “tswit-tswit” call is given when a bird of prey such as Sparrowhawk or Peregrine is spotted.

Diet

Swallows feed almost exclusively on insects (midges, flies) caught in flight.

Breeding

Constructs a bowl-shaped nest out of mud in suitable spots in barns and other buildings.

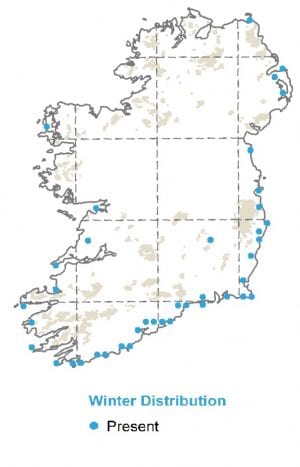

Wintering

Swallows spend the winter in southern Africa, migrating across the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert in spring and autumn.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

World Migratory Bird Day campaign underscores the importance of insects and shines a light on declines

Saturday, October 12th marks World Migratory Bird Day. By focusing their 2024 campaign on insects, organisers hope to underscore their importance to migratory birds while also highlighting wider concerns related to decreasing insect populations.

The importance of insects for migratory birds and all life

We often hone in on the long distances travelled by migratory bird species and rightly so. It is extremely impressive that such small creatures can fly thousands of miles, often in challenging weather conditions, and arrive at their destination safely. However, many birds are reliant on other species to make this journey possible. Indeed, it is the existence of other winged creatures – insect populations – that gives them the fuel to keep on going.

Insects are essential food sources for many migratory birds on their long journeys, and some species will time their migrations to align with periods of insect abundance in their stopover locations. Once they replenish their energy reserves, they can resume their journey.

Species such as warblers, flycatchers, swallows, and swifts are particularly reliant on insects. However, many other bird species such as ducks and shorebirds depend on insects during migration and at other stages in their lifecycle, in particular for raising their young before they are able to fly.

On a wider level, insects provide critical ecosystem services that support all life on this planet. They pollinate crops which supports food production, decompose waste materials and contribute to nutrient cycling and soil fertility, and control pests. Their decline has a direct impact on ecosystem functioning.

Insect Declines

Many people will recall how, not so long ago, a large number of dead insects would be found on a car windscreen and bumper following a drive through the countryside. Those too young to have experienced this period of insect abundance are likely to have heard this anecdote from friends and family. In fact, it is such a widely shared observation that it has become known to entomologists as the “the windshield phenomenon”.

Anecdotally, insects have experienced declines, but what does the science say? Unfortunately, invertebrates including insects have been historically understudied and many gaps in the data still remain. Additionally, where assessments have taken place, they have predominantly been in regions that can afford to fund insect science such as Europe and North America. Some of the most biodiverse regions on the planet have had little to no assessments of their insect populations. This lack of data on the species we know, coupled with the fact that millions of insect species are yet to be discovered, suggests that we don’t have the full picture on the scale of global insect decline.

However, in recent decades, efforts to better understand how insects are faring have expanded with pollinating insects such as bees, hoverflies, butterflies and moths in particular becoming the subject of an increased amount of research. From what we know so far, the situation is clear: they are in peril.

For example, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) European Red List of Bees shows that 9% of the 1,965 species of bee in Europe are Threatened with extinction mainly due to habitat loss as a result of agriculture intensification, urban development, increased frequency of fires and climate change. A further 5.2% are considered Near Threatened. However, a staggering 56.7% of these species were classified as “Data Deficient” meaning that there is not enough data to evaluate their risk of extinction.

Over 37% of the European hoverfly species assessed in the IUCN European Red List of Hoverflies were considered Threatened, with a further 6.9% considered Near Threatened. One species that previously occurred in Sweden, Finland and possibly Poland, was classified as Regionally Extinct.

As outlined in their Red List Strategic Plan (2021-2030), the IUCN is working to substantially increase the number of wild species assessed, particularly plants, invertebrates and fungi.

Insects in Ireland

In Ireland, the National Biodiversity Data Centre is doing trojan work to improve our knowledge of insect populations in Ireland, particularly via monitoring schemes for butterflies, bumblebees and more recently, dragonflies.

The Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme, established by the Data Centre in 2008, is Ireland’s longest-running citizen science insect monitoring scheme. By tracking changes in 15 species, we now know that overall butterfly populations have declined by 55% since 2008.

Meanwhile, the All-Ireland Bumblebee Monitoring Scheme has been tracking changes in the populations of the eight most common bumblebee species since 2012. The current overall trend from 2012-2023 is a year-on-year decline of 3.3%.

Celebrate World Migratory Bird Day

World Migratory Bird Day is an annual global campaign dedicated to raising awareness of migratory birds and the need for international cooperation to conserve them. It is organised by a collaborative partnership among two UN treaties – the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement (AEWA) – and the non-profit organisation, Environment for the Americas (EFTA).

The return of winter migrants to Ireland brings a seasonal spectacle as thousands of birds, such as Whooper Swans, Greenland White-fronted Geese and Greylag Geese arrive from colder northern regions. This annual migration highlights Ireland's role as a vital sanctuary, providing essential habitats for these species during the harsher winter months. Keep an eye out for some of these species this World Migratory Bird Day but be sure to keep your distance to avoid harmful disturbance.

This year’s insect theme may also encourage you to play your part for Ireland’s insect populations. One way you can do this is by getting involved in the National Biodiversity Data Centre’s citizen science initiatives. Find out more here.

Q & A with Brian Burke - Project Manager of the Little Tern Project in Kilcoole

Marine Policy Officer, Rosalind Skillen, speaks to Little Tern Project Manager, Brian Burke about the The Little Tern Conservation Project in Kilcoole.

This is a National Parks and Wildlife Service project which is managed by Birdwatch Ireland. It is by far the largest Little Tern colony in Ireland, having grown from under fewer than 20 nesting pairs in the 1980s to 274 pairs in 2024.

Can you tell us a bit about Little Terns, the species you work to protect?

Little Terns are fantastic little birds. They weigh around 50g, so around half the size of a Blackbird. Terns were historically known as ‘sea swallows’ as they have a shape similar to a Swallow, with long pointed wings and forked tails, but are white and ‘marine’ in nature like a gull. These tiny little birds migrate to West Africa in the winter, and return to a number of out-of-the-way sand and shingle beaches around the Irish coast to try and raise their young. As seabirds that rely on a diet of fish, they’re excellent ecosystem indicators to give us an idea of what goes on beneath the waves. If Little Terns are doing well and raising young successfully, it must mean that the sea around their colony has enough fish to support them.

Have you noticed any changes in populations or behaviours over the years?

The biggest change has been the numbers at the Kilcoole colony. We now have by far the biggest colony of Little Terns in Ireland, and one of the biggest in all of Ireland and the UK, and that’s thanks to many years of conservation efforts by the National Parks and Wildlife Service and BirdWatch Ireland. I think it’s a real testament to long-term funding and long-term efforts. Sometimes it can take a few years for your efforts to be rewarded, but when it comes to scarce and declining species, we need to stick with it. We still have occasional bad years at Kilcoole, but importantly we now have many more good years than bad and the Kilcoole and east coast population as a whole are growing.

Have you noticed any changes in populations or behaviours over the years?

The biggest change has been the numbers at the Kilcoole colony. We now have by far the biggest colony of Little Terns in Ireland, and one of the biggest in all of Ireland and the UK, and that’s thanks to many years of conservation efforts by the National Parks and Wildlife Service and BirdWatch Ireland. I think it’s a real testament to long-term funding and long-term efforts. Sometimes it can take a few years for your efforts to be rewarded, but when it comes to scarce and declining species, we need to stick with it. We still have occasional bad years at Kilcoole, but importantly we now have many more good years than bad and the Kilcoole and east coast population as a whole are growing.

How do you involve the local community at Kilcoole?

The local community in Kilcoole are fantastic every year. They’re always delighted to see the Terns back, and indeed are sometimes concerned towards the end of April when we haven’t got all our fencing up yet! Something as simple as people walking on the beach, and letting dogs off leashes, are some of the biggest threats to Little Terns but everyone at Kilcoole is very happy to steer clear of the nesting area once the terns are back, and that makes a big difference. There’s a real sense of pride in Kilcoole around having these birds pick here to nest, and there’s a ‘Little Tern Playground’ in Kilcoole and one of the schools even has terns on their crest! Ultimately, many conservation problems are people problems rather than ecological problems. We know what most species need to thrive, but we need public buy-in to actually provide it. Thankfully the local community at Kilcoole are incredibly supportive.

How do you involve the local community at Kilcoole?

The local community in Kilcoole are fantastic every year. They’re always delighted to see the Terns back, and indeed are sometimes concerned towards the end of April when we haven’t got all our fencing up yet! Something as simple as people walking on the beach, and letting dogs off leashes, are some of the biggest threats to Little Terns but everyone at Kilcoole is very happy to steer clear of the nesting area once the terns are back, and that makes a big difference. There’s a real sense of pride in Kilcoole around having these birds pick here to nest, and there’s a ‘Little Tern Playground’ in Kilcoole and one of the schools even has terns on their crest! Ultimately, many conservation problems are people problems rather than ecological problems. We know what most species need to thrive, but we need public buy-in to actually provide it. Thankfully the local community at Kilcoole are incredibly supportive.

What are the biggest threats to Little Terns in Kilcoole?

The biggest threats are predators, and waves. A single fox, or a determined Hooded Crow, Rook or Mink, could do a huge amount of damage in a very short space of time to a colony like this. Unfortunately in recent decades we’ve made the Irish landscape perfect for ‘mesopredators’ like these, and much less suitable for specialist species like the Little Tern. So we try and restore that balance on the beach at Kilcoole to give the Terns a chance. Similarly though, windy days, combined with a high tide can spell disaster for the colony and we’ve had huge amounts of eggs and chicks washed away in a couple of hours. Unfortunately there’s nothing you can do to stop the sea swell when conditions are like that, and with climate change and stormier and more unpredictable weather each summer it's something we’re going to keep seeing in the years ahead.

What are the biggest threats to Little Terns in Kilcoole?

The biggest threats are predators, and waves. A single fox, or a determined Hooded Crow, Rook or Mink, could do a huge amount of damage in a very short space of time to a colony like this. Unfortunately in recent decades we’ve made the Irish landscape perfect for ‘mesopredators’ like these, and much less suitable for specialist species like the Little Tern. So we try and restore that balance on the beach at Kilcoole to give the Terns a chance. Similarly though, windy days, combined with a high tide can spell disaster for the colony and we’ve had huge amounts of eggs and chicks washed away in a couple of hours. Unfortunately there’s nothing you can do to stop the sea swell when conditions are like that, and with climate change and stormier and more unpredictable weather each summer it's something we’re going to keep seeing in the years ahead.

What can we do to support your work?

I think the Kilcoole Little Tern conservation project is a fantastic example of what can be achieved with long-term funding and continued efforts to address conservation problems and develop expertise over time. Kilcoole wasn’t an immediate success, but over time we’ve worked closely with NPWS to address the issues the birds face and to get to the stage where we have more good years than bad years. I think we need more protected sites, offshore and onshore, and we need to get plans and resources in place to reverse the biodiversity declines that are happening. Monitoring is important too – we need to know what we have, where we have it, and how it’s changing over time. The only way we’ll know if protection and conservation efforts are working is with continued monitoring. And importantly, we need to start now – there’s no time to waste!

[Photos 1-3: Brian Burke; Photo 4 (Ringing Photo): Oonagh Duggan]

The Kilcoole Little Tern Project is an NPWS project run by BirdWatch Ireland under a competitive tender agreement in 2024.

What can we do to support your work?

I think the Kilcoole Little Tern conservation project is a fantastic example of what can be achieved with long-term funding and continued efforts to address conservation problems and develop expertise over time. Kilcoole wasn’t an immediate success, but over time we’ve worked closely with NPWS to address the issues the birds face and to get to the stage where we have more good years than bad years. I think we need more protected sites, offshore and onshore, and we need to get plans and resources in place to reverse the biodiversity declines that are happening. Monitoring is important too – we need to know what we have, where we have it, and how it’s changing over time. The only way we’ll know if protection and conservation efforts are working is with continued monitoring. And importantly, we need to start now – there’s no time to waste!

[Photos 1-3: Brian Burke; Photo 4 (Ringing Photo): Oonagh Duggan]

The Kilcoole Little Tern Project is an NPWS project run by BirdWatch Ireland under a competitive tender agreement in 2024.

Have you noticed any changes in populations or behaviours over the years?

The biggest change has been the numbers at the Kilcoole colony. We now have by far the biggest colony of Little Terns in Ireland, and one of the biggest in all of Ireland and the UK, and that’s thanks to many years of conservation efforts by the National Parks and Wildlife Service and BirdWatch Ireland. I think it’s a real testament to long-term funding and long-term efforts. Sometimes it can take a few years for your efforts to be rewarded, but when it comes to scarce and declining species, we need to stick with it. We still have occasional bad years at Kilcoole, but importantly we now have many more good years than bad and the Kilcoole and east coast population as a whole are growing.

Have you noticed any changes in populations or behaviours over the years?

The biggest change has been the numbers at the Kilcoole colony. We now have by far the biggest colony of Little Terns in Ireland, and one of the biggest in all of Ireland and the UK, and that’s thanks to many years of conservation efforts by the National Parks and Wildlife Service and BirdWatch Ireland. I think it’s a real testament to long-term funding and long-term efforts. Sometimes it can take a few years for your efforts to be rewarded, but when it comes to scarce and declining species, we need to stick with it. We still have occasional bad years at Kilcoole, but importantly we now have many more good years than bad and the Kilcoole and east coast population as a whole are growing.

How do you involve the local community at Kilcoole?

The local community in Kilcoole are fantastic every year. They’re always delighted to see the Terns back, and indeed are sometimes concerned towards the end of April when we haven’t got all our fencing up yet! Something as simple as people walking on the beach, and letting dogs off leashes, are some of the biggest threats to Little Terns but everyone at Kilcoole is very happy to steer clear of the nesting area once the terns are back, and that makes a big difference. There’s a real sense of pride in Kilcoole around having these birds pick here to nest, and there’s a ‘Little Tern Playground’ in Kilcoole and one of the schools even has terns on their crest! Ultimately, many conservation problems are people problems rather than ecological problems. We know what most species need to thrive, but we need public buy-in to actually provide it. Thankfully the local community at Kilcoole are incredibly supportive.

How do you involve the local community at Kilcoole?

The local community in Kilcoole are fantastic every year. They’re always delighted to see the Terns back, and indeed are sometimes concerned towards the end of April when we haven’t got all our fencing up yet! Something as simple as people walking on the beach, and letting dogs off leashes, are some of the biggest threats to Little Terns but everyone at Kilcoole is very happy to steer clear of the nesting area once the terns are back, and that makes a big difference. There’s a real sense of pride in Kilcoole around having these birds pick here to nest, and there’s a ‘Little Tern Playground’ in Kilcoole and one of the schools even has terns on their crest! Ultimately, many conservation problems are people problems rather than ecological problems. We know what most species need to thrive, but we need public buy-in to actually provide it. Thankfully the local community at Kilcoole are incredibly supportive.

What are the biggest threats to Little Terns in Kilcoole?

The biggest threats are predators, and waves. A single fox, or a determined Hooded Crow, Rook or Mink, could do a huge amount of damage in a very short space of time to a colony like this. Unfortunately in recent decades we’ve made the Irish landscape perfect for ‘mesopredators’ like these, and much less suitable for specialist species like the Little Tern. So we try and restore that balance on the beach at Kilcoole to give the Terns a chance. Similarly though, windy days, combined with a high tide can spell disaster for the colony and we’ve had huge amounts of eggs and chicks washed away in a couple of hours. Unfortunately there’s nothing you can do to stop the sea swell when conditions are like that, and with climate change and stormier and more unpredictable weather each summer it's something we’re going to keep seeing in the years ahead.

What are the biggest threats to Little Terns in Kilcoole?

The biggest threats are predators, and waves. A single fox, or a determined Hooded Crow, Rook or Mink, could do a huge amount of damage in a very short space of time to a colony like this. Unfortunately in recent decades we’ve made the Irish landscape perfect for ‘mesopredators’ like these, and much less suitable for specialist species like the Little Tern. So we try and restore that balance on the beach at Kilcoole to give the Terns a chance. Similarly though, windy days, combined with a high tide can spell disaster for the colony and we’ve had huge amounts of eggs and chicks washed away in a couple of hours. Unfortunately there’s nothing you can do to stop the sea swell when conditions are like that, and with climate change and stormier and more unpredictable weather each summer it's something we’re going to keep seeing in the years ahead.

What can we do to support your work?

I think the Kilcoole Little Tern conservation project is a fantastic example of what can be achieved with long-term funding and continued efforts to address conservation problems and develop expertise over time. Kilcoole wasn’t an immediate success, but over time we’ve worked closely with NPWS to address the issues the birds face and to get to the stage where we have more good years than bad years. I think we need more protected sites, offshore and onshore, and we need to get plans and resources in place to reverse the biodiversity declines that are happening. Monitoring is important too – we need to know what we have, where we have it, and how it’s changing over time. The only way we’ll know if protection and conservation efforts are working is with continued monitoring. And importantly, we need to start now – there’s no time to waste!

[Photos 1-3: Brian Burke; Photo 4 (Ringing Photo): Oonagh Duggan]

The Kilcoole Little Tern Project is an NPWS project run by BirdWatch Ireland under a competitive tender agreement in 2024.

What can we do to support your work?

I think the Kilcoole Little Tern conservation project is a fantastic example of what can be achieved with long-term funding and continued efforts to address conservation problems and develop expertise over time. Kilcoole wasn’t an immediate success, but over time we’ve worked closely with NPWS to address the issues the birds face and to get to the stage where we have more good years than bad years. I think we need more protected sites, offshore and onshore, and we need to get plans and resources in place to reverse the biodiversity declines that are happening. Monitoring is important too – we need to know what we have, where we have it, and how it’s changing over time. The only way we’ll know if protection and conservation efforts are working is with continued monitoring. And importantly, we need to start now – there’s no time to waste!

[Photos 1-3: Brian Burke; Photo 4 (Ringing Photo): Oonagh Duggan]

The Kilcoole Little Tern Project is an NPWS project run by BirdWatch Ireland under a competitive tender agreement in 2024.