Skylark

| Irish Name: | Fuiseog |

| Scientific name: | Alauda arvensis |

| Bird Family: | Skylarks |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

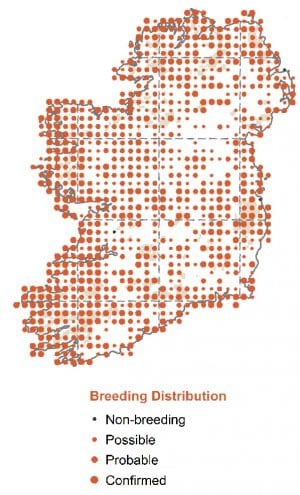

Common resident throughout Ireland in uplands and areas of farmland, especially cereal.

Identification

A rather non-descript species, with much brown and black streaking. Adult Skylarks have a prominent white supercilium and frequently raise their crown feathers to form a little crest. Juveniles have much of the black streaking replaced by spotting and lack the crest. When flushed from the ground, keeps close to the ground unlike the similar Meadow Pipit which typically rises straight up.

Voice

Rather vocal. Commonest call is a “chirrup” or “trrrp” given in flight. The song, which can be heard from February/March to June, is a distinctive continuous stream of warbling notes. It can last up to half an hour and is usually given while the bird is flying 50 to 100 metres overhead.

Diet

Skylarks feed on a variety of insects, seeds and plant leaves.

Breeding

Breeds in a variety of habitats including cultivated areas, ungrazed grasslands and upland heaths.

Wintering

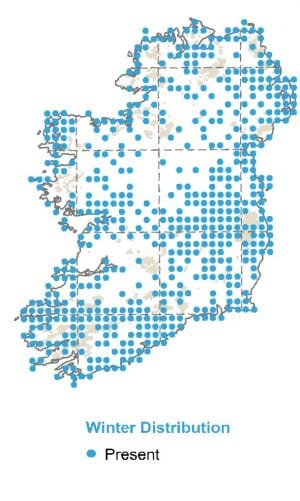

Usually moves out of breeding areas to winter in flocks on stubble fields, grasslands and coastal areas. Birds from continental Europe arrive in variable numbers from September and depart March/April.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

BirdWatch Ireland welcomes the scrapping of the winter stubble rule

BirdWatch Ireland is pleased that the rule for shallow cultivation of winter stubbles has been scrapped in the latest iteration of the Nitrates Action Programme. It is regrettable, however, that this decision was not made sooner, and particularly before farmers cultivated stubble grounds in 2025, leaving threatened bird species looking for other food supplies this winter. In the medium and long term, Ireland’s Common Agriculture Policy Strategic Plan and National Restoration Plan must incentivise farmers to provide sufficient quantity and quality of habitats to restore both wintering and breeding farmland bird populations.

The controversial winter stubble rule was introduced in 2022, despite vociferous opposition from BirdWatch Ireland on account of the risk of severe impacts to farmland birds over the winter months, when food supplies for many Red- and Amber-Listed Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland are in short supply.

The stubble fields left after crops have been harvested often harbour spilled seeds, which seed-eating birds, such as the Yellowhammer and the Skylark, and rodents will consume during the cold winter. These small birds and mammals are prey species for other birds, including the Hen Harrier, a highly protected and increasingly rare bird of prey that is experiencing ongoing declines. In our submission to government at that time, we highlighted that 30 Red- or Amber-Listed Birds of Conservation in Ireland relied on winter stubbles for food.

Nesting Season 101 – Hedge-cutting and the Law

Birds in Ireland are facing pressures from all sides, with habitat loss and fragmentation, predation, disturbance and climate change just some of the things they have to contend with. Nesting birds and their young are particularly vulnerable and, while it is vital that we don’t interfere with wild birds at this time, there are some things you can do to support birds during nesting season. One of the easiest ways to do so is to abide by existing laws around hedge-cutting and vegetation burning.

Hedge-cutting and vegetation burning ban

Under the Wildlife Act, it is against the law to cut, burn or otherwise destroy vegetation including hedges between March 1st and August 31st. The purpose of this ban is to prevent the disturbance and destruction of nesting sites of many of our wild bird species.Hedge-cutting

Hedges provide important nesting sites for many wild birds – including Robin, Wren, Blackbird, and Dunnock, to name a few – as well as a bounty of food for a variety of other species. They also offer shelter and safe routes for wildlife to travel along, known as wildlife corridors. Hedges offer numerous benefits to humans including food, natural property boundaries, shelter for crops and livestock, noise reduction and visual appeal. As healthy hedges also sequester and store atmospheric carbon, and help to slow water movement and prevent flooding, they are absolutely vital in mitigating the effects of climate change. While some green-fingered folk may argue that, with a steady hand, they can leave a nest unshaken, the sheer act of getting that close to the hedge and nests within it could be enough for the adult birds to abandon it. Without their parents, the eggs and chicks in the nest have virtually no hope of survival. If they don’t succumb to starvation due to lack of food delivery by an adult bird, they are likely to be victims of predation. 63% of regularly occurring Irish birds are of serious conservation concern, with 26% of them now Red-listed species of conservation concern and 37% Amber-listed species of conservation concern. With the decline in bird populations directly linked to the loss and degradation of habitat, it is important that we do all we can to preserve what remains. You can play your part in this by leaving your hedges alone during the nesting season, and by spreading the word to others.Wren. Photo: Michael Finn.

Vegetation Burning

The Wildlife Act also prohibits the burning of vegetation during the nesting season. This is aimed at protecting our ground-nesting bird species in upland habitats, many of which have seen their populations plummet in recent decades. This includes species such as Curlew, Lapwing, Skylark, Meadow Pipit and Hen Harrier. While burning is not the only cause of the decline of these species, it does pose a significant threat to their breeding success when carried out during the nesting period. But even during the 'open season' for burning, out-of-control fires, can have devastating consequences on habitats sometimes 'melting' peat soils due to the heat and destroying their functions as carbon stores and sinks as well as habitats for wildlife, for years. Illegal fires during the closed period can lead to the destruction of nests and young of these already vulnerable species, as well as the disturbance of breeding adults. Additionally, such burning can damage habitats that are protected in their own right such as Raised Bog and Blanket Bog. In addition to being unique and biodiverse habitats, our bogs serve as carbon sinks, meaning that they play a huge role in mitigating the effects of climate change.

Reporting illegal cutting and burning

Despite the ban on hedge-cutting between March 1st and August 31st, it is possible that you will come across cutting and burning during this period. Indeed, the Wildlife Act does have exemptions which allow hedge-cutting during the closed period, for example, should there be road safety concerns. In saying this, regardless of who is involved, don’t assume that those cutting the hedge have received the green light to do so. It may well be that they are breaking the law. If you witness hedge-cutting or burning in any place or at any time during this period, please report it to the local Gardaí and the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS). You can read the NPWS guidance on reporting Wildlife Crime here and find contact details for your local NPWS Wildlife Ranger here.Enforcement of the Wildlife Act

Efforts to tackle wildlife crime in Ireland have been strengthened in recent times. Forty-three prosecution cases were initiated by NPWS in 2023 for alleged breaches of wildlife legislation, a 39% increase since 2022. Wildlife crimes reported range from the disturbance of bats, illegal hunting, damage to Special Areas of Conservation (SACs), destruction of hedgerows and burning of vegetation within the restricted period, and more. This increase in action against wildlife crime is very much welcomed by us at BirdWatch Ireland. However, there is still work to be done. It is widely known that our wildlife legislation is not as strongly enforced as it could be, and that the initiation of cases and rates of conviction are higher in some locations than others. There are a number of reasons for this including a general lack of training and resources in the area of wildlife crime in both the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) and An Garda Siochána, and difficulty in gathering sufficient evidence on certain forms of wildlife crime. With this in mind, if you witness any other form of wildlife crime, or simply are worried about the situation for wildlife in this country, we would encourage you to also contact your local and national elected representatives to voice your concerns.