Lesser Black-backed Gull

| Irish Name: | Droimneach beag |

| Scientific name: | Larus fuscus |

| Bird Family: | White-headed Gulls |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

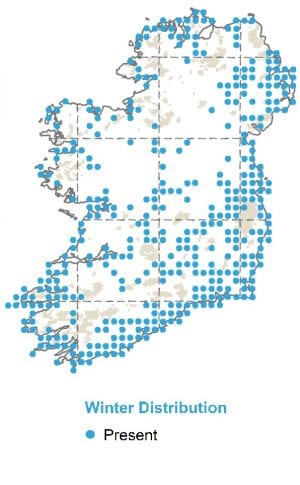

Summer visitor to lakes and coasts from March to September, wintering in Iberia and northwest Africa. Winter visitor in small numbers along eastern and southern coasts, probably from Iceland and the Faeroe Islands.

Identification

A large gull, which in adult plumage has dark grey upperwings, showing black tips with white 'mirrors' (white at the very tips surrounded by black); the rest of the plumage is white. Adult birds have heavy yellow bills with a orange spot on the lower bill, the head is pure white in the summer and streaked in the winter; the legs are yellow. Lesser Black-backed Gulls have four age groups and attain adult plumage after three years when they moult into adult winter plumage. Juveniles are grey with finely patterned feathers which fade in the first year, especially the wing and tail feathers which are retained through the first summer. Juvenile and first year birds do not have any plain dark grey adult like feathers in the upperparts and can be difficult to tell apart from immature Herring Gulls and Great Black-back gulls. Dark grey in the upperparts develops from the second winter onwards, initially mostly in the mantle and back and becomes more extensive over the wings as the bird moves towards maturity. Younger immature birds have a dark terminal tail band which becomes less prominent as they get older, adult birds lack this band completely.

Voice

Similar to Herring Gull, but more nasal and deeper in tone.

Diet

Takes a wide variety of prey including fish from the sea, waste from fisheries, rubbish from landfill sites, insects in flight, young birds and food from other birds.

Breeding

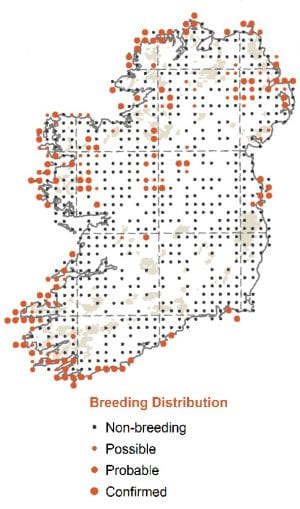

Breeds colonially, often with other gull species especially Herring Gull. Nests on the ground. Will use a variety of sites, including off shore islands, islands in inland lakes, sand dunes and coastal cliffs. Small numbers also nest on roof tops in Co. Dublin. Most colonies in Ireland are on the coast, mostly on the west coast. Most inland colonies are found in Co. Mayo and in Co. Donegal

Wintering

In the winter, the species is found in a wide variety of habitats both inland and along the south and east coasts. The largest numbers occur after the breeding season in autumn when migrating birds pass through Ireland in great numbers.

Monitored by

Wintering birds are monitored through the Irish Wetland Bird Survey. Breeding seabirds are monitored through breeding seabird surveys carried out every 15-20 years.

Blog posts about this bird

New protected area off Wexford coast is a step forward for vulnerable seabirds

The recent announcement of the new “Seas off Wexford” Special Protection Area (SPA) is certainly news to be welcomed.

For such a designation to be as effective as it can be, it is crucial that strong and effective conservation objectives and management plans are ambitious and that stakeholders are consulted throughout the process. It would be most welcome if the designation of new marine SPAs also led to a new vision for management of Ireland’s entire network of SPAs. BirdWatch Ireland calls on government to ensure that management plans are put in place for SPAs on both land and sea and that a whole-of-government approach is taken to implement them properly to safeguard the future of the birds they are intended to protect.

Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage Darragh O’Brien recently designated the new SPA of marine waters off the coast of Wexford which, at over 305,000 hectares, is the largest SPA designated in the history of the state. These waters provide extremely important food sources for seabirds, including Red-listed species such as Puffin, Kittiwake, Common Scoter and many other vulnerable Amber-listed species such as Fulmar, Manx Shearwater, Shag, Cormorant, Black-headed Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull, Herring Gull, Roseate Tern, Red-throated Diver, Gannet, Common Tern, Little Tern, Sandwich Tern, Mediterranean Gull and Guillemot.

Kittiwake. Photo: Colum Clarke.

Under EU legislation, the Irish government has made a commitment to designate 10% of its waters as protected by 2025, and a total of 30% by 2030. This new designation increases the percentage of Ireland’s marine protected waters to 9.4%, just under the 2025 target. While this is certainly a step in the right direction, many questions remain, primarily, what will “protection” look like in practice? It is paramount that this is made clear in the soon-to-be-published SPA’s conservation objectives, which should detail the activities that will and will not be permitted in the SPA, among other measures. We look forward to reading them shortly. At the same time, BirdWatch Ireland in collaboration with BirdLife Europe and BirdLife International are mapping Ireland’s marine Important Bird Areas according to international and standardised BirdLife International criteria under a project funded by the Flotilla Foundation. This is an important time for our seabirds and it is welcome to see the government’s focus finally on setting out protected areas for them.

Red-throated Diver. Photo: Chris Gomersall

While the finer details about the Wexford SPA have yet to come to light, it is clear that certain activities will not be permitted in the Wexford SPA. The Minister has issued a Direction in relation to certain activities, which must not be carried out within or close to the SPA, unless consent is lawfully given. The listed activities are reclamation including infilling; blasting, drilling, dredging or otherwise disturbing or removing fossils, rock, minerals, mud, sand, gravel or other sediment; introduction or reintroduction of plants or animals not found in the area; scientific research which involves the removal of biological material; any activity intended to disturb birds; undertaking acoustic surveys in the marine environment and developing or consenting to the development or operation of commercial recreational/ visitor facilities or organised recreational activities.

Little Terns.

Together with our partners at Fair Seas – a coalition of Ireland’s leading environmental NGOs and environmental networks of which BirdWatch Ireland is a founding member – we have been calling for the government to meet their targets, but this alone is not enough. More action must be taken in order for us to adequately protect these important marine habitats and the many species that they support. Any move to better protect important habitats for birds is to be welcomed, and this is certainly no different. We are urging the Irish government to be ambitious in their plans for this new SPA and stress the need for focused community engagement in the surrounding areas. We also continue our urgent calls for the publication of the long-awaited Marine Protected Areas (MPA) Bill.

Urban Gulls, BirdWatch Ireland’s view from the roof-tops

Love them or loathe them, ‘seagulls in the city’, are here to stay.

Firstly, some facts: Seagulls, NO! Just 'gulls', and in summer months in urban areas they can be any of three species: Herring Gull, Lesser Black-backed and Great Black-backed Gull. In the last two decades many of these have ‘moved away’ from their mostly coastal haunts and now can be found almost anywhere in the country – cities, parks, farmland, lakes and reservoirs, coasts, harbours, islands. Herring Gulls and Lesser Black-backed Gulls have taken to nesting on roofs but ‘Greats’ still mostly nest on coastal cliffs and islands. The majority of urban nesting gulls are Herring Gulls.

Herring Gulls traditionally nest along the coast but now commonly nest on rooftops in some urban areas.

Twenty years ago, there were only a couple of hundred urban/roof-nesting gulls – mostly in Dublin City and the north County Dublin towns of Howth, Skerries and Balbriggan with a few more in the south coast fishing port of Dunmore East, County Waterford. Since then, the population has increased dramatically and almost certainly numbers in the thousands of pairs. The National Parks & Wildlife Service have initiated a systematic survey of urban-nesting gulls in spring/summer 2021 and following this we ought to have an idea of the true magnitude of the population increase. On the coasts, a comprehensive national survey spanning 2015-2019, showed that all three species have increased modestly (30-40%) for Herring and Great Back-backed over 15-20 years, whereas the Lesser Black-backed Gull have increased more dramatically (148%) in the same period. Much of the increase in Lesser Black-backed Gulls has been seen on large lakes in the west (again, not seagulls!). These increases suggest that species such as the Herring Gull have recovered from earlier declines which had resulted in them being Red-listed (i.e. of serious conservation concern). How the urban-nesting gulls ‘interact’ with, or differ from, coastal gulls is a key question that will require some new research looking at movement patterns, diet and feeding ecology, and recruitment of young. Taking these topics individually…

Movements

Dublin is a coastal City with a large tidal river (Liffey) flowing through the middle of it. Do gulls become urban or coastal specialists or do they move regularly back and forth from coastal and intertidal habitats to city parks and streets, eating shellfish one day and discarded takeaway leftovers the next? Resightings of the increasing numbers of individually identifiable colour ringed gulls (by the Irish Midlands Ringing Group) is vital to this. Movements may be driven more by other aspects of behaviour e.g. birds on the streets by day may move to roost in Dublin Bay at night. Deployment of GPS tags and colour ring ‘reads’ will help in this regard.

How the urban-nesting gulls ‘interact’ with, or differ from, coastal gulls is a key question that will require some new research looking at movement patterns, diet and feeding ecology, and recruitment of young. Taking these topics individually…

Movements

Dublin is a coastal City with a large tidal river (Liffey) flowing through the middle of it. Do gulls become urban or coastal specialists or do they move regularly back and forth from coastal and intertidal habitats to city parks and streets, eating shellfish one day and discarded takeaway leftovers the next? Resightings of the increasing numbers of individually identifiable colour ringed gulls (by the Irish Midlands Ringing Group) is vital to this. Movements may be driven more by other aspects of behaviour e.g. birds on the streets by day may move to roost in Dublin Bay at night. Deployment of GPS tags and colour ring ‘reads’ will help in this regard.

Some gulls are 'tagged' with a leg ring, similar to the one above. If you see one, be sure to report it, to help shed more light on their movements.

Diet Are all urban nesting or wintering (in parks etc.) gulls dependent on human waste? Can we do more with local authorities, schools and communities to cut littering and dissuade people from feeding gulls in public parks and other green spaces?

The way we manage our waste is a big factor in the increased numbers of urban gulls in recent years.

Recruitment of young Will a chick reared on a rooftop always go on to breed on a rooftop when it reaches maturity at about 4-years of age? And, ditto for birds reared on islands such as Dalkey and Ireland’s Eye? A very important piece of evidence arose on 24 May 2021 when an opportunistic ring read of an adult Lesser Black-back nesting on Dalkey Island was shown to be one of a brood ringed on the roof of the National Gallery in the heart of D2 in 2017!

Recent research indicates that not all chicks from urban nests return to towns and cities to nest. More research is needed to learn about the relationship between the gulls natural and urban-nesting sites and how they're linked.

Perhaps the most important issue to many city residents is the impact of gulls on human health and well-being. The regularly listed complaints include, food theft (while people eat in the streets and parks), early morning noise (disrupting sleep patterns etc.), physical harassment (by aggressive nest and chick-defending adults); mess from droppings fouling clean clothes on washing lines or on parked cars. There is no magic cure, but one step at a time, we have to make cities less attractive habitat to gulls, and food availability is at the core of this issue. We need to do more, individually and collectively to reduce this via changes in personal behaviour, refuse collection strategies etc. We are not going to make roofs less attractive nesting sites (without great structural expenditure) but if we reduce food availability then numbers ought to decline in the long-term.