Manx Shearwater

| Irish Name: | Cánóg dhubh |

| Scientific name: | Puffinus puffinus |

| Bird Family: | Tubenoses |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

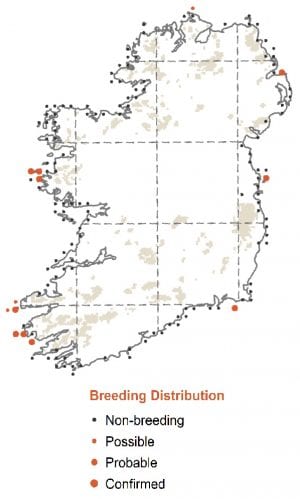

Summer visitor to all coasts from March to August.

Identification

A black and white seabird, black above and white below. Long narrow wings, which are used for gliding low over waves, with hardly a wing beat employed to aid flight. Characteristic switchback flight action with bird banking over waves, which it employs for lift, showing black and then white, then black and so on. Straight bill with hooked tip and tube-shaped nostrils on the upper mandible, giving distinctive bill shape if seen at close range. Nostrils used to excrete salt. Confusion with other seabirds unlikely. Confusion with other species of rare shearwater, which are sometimes found in Irish water in good numbers, possible in the late summer.

Voice

Calls at colonies. Eerie, loud, raucous, chuckling or cackling "sgaga-cack-cack-cack", rising and descending with frequent high-pitched "hyterical" notes. Silent when at sea

Diet

Taken from the sea by diving. Small fish, plankton, molluscs and crustaceans.

Breeding

Spends most of its life at sea and only comes to land in the breeding season, which is protracted, through the summer. Mostly breeds on uninhabited off-shore islands, largely free from mammalian predators, often in huge numbers. Breeds underground in burrows and will only return to colonies on dark, moonless nights. Manx Shearwaters cannot walk on land and can only drag themselves over the ground and into their burrows, making them vulnerable to gull predation. In Ireland, the largest colonies are found in Co. Kerry, with the Blasket Islands having the greatest numbers. Colonies are also found on the east coast, on the Saltees off Co. Wexford and Copeland Island, Co. Down. Birds at sea could also be from British colonies, Britain has 90% of the world population, with large colonies on Rhum in Scotland, as well as on the Pembrokeshire Islands.

Wintering

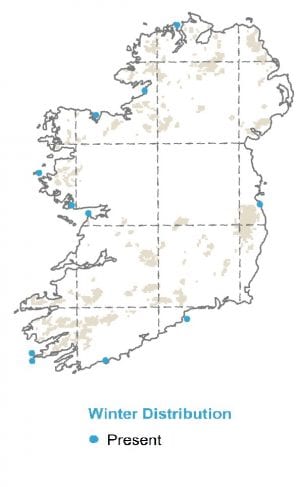

Winters at sea in the South Atlantic off South America.

Monitored by

Breeding seabirds are monitored through breeding seabird surveys carried out every 15-20 years.

Blog posts about this bird

New protected area off Wexford coast is a step forward for vulnerable seabirds

The recent announcement of the new “Seas off Wexford” Special Protection Area (SPA) is certainly news to be welcomed.

For such a designation to be as effective as it can be, it is crucial that strong and effective conservation objectives and management plans are ambitious and that stakeholders are consulted throughout the process. It would be most welcome if the designation of new marine SPAs also led to a new vision for management of Ireland’s entire network of SPAs. BirdWatch Ireland calls on government to ensure that management plans are put in place for SPAs on both land and sea and that a whole-of-government approach is taken to implement them properly to safeguard the future of the birds they are intended to protect.

Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage Darragh O’Brien recently designated the new SPA of marine waters off the coast of Wexford which, at over 305,000 hectares, is the largest SPA designated in the history of the state. These waters provide extremely important food sources for seabirds, including Red-listed species such as Puffin, Kittiwake, Common Scoter and many other vulnerable Amber-listed species such as Fulmar, Manx Shearwater, Shag, Cormorant, Black-headed Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull, Herring Gull, Roseate Tern, Red-throated Diver, Gannet, Common Tern, Little Tern, Sandwich Tern, Mediterranean Gull and Guillemot.

Kittiwake. Photo: Colum Clarke.

Under EU legislation, the Irish government has made a commitment to designate 10% of its waters as protected by 2025, and a total of 30% by 2030. This new designation increases the percentage of Ireland’s marine protected waters to 9.4%, just under the 2025 target. While this is certainly a step in the right direction, many questions remain, primarily, what will “protection” look like in practice? It is paramount that this is made clear in the soon-to-be-published SPA’s conservation objectives, which should detail the activities that will and will not be permitted in the SPA, among other measures. We look forward to reading them shortly. At the same time, BirdWatch Ireland in collaboration with BirdLife Europe and BirdLife International are mapping Ireland’s marine Important Bird Areas according to international and standardised BirdLife International criteria under a project funded by the Flotilla Foundation. This is an important time for our seabirds and it is welcome to see the government’s focus finally on setting out protected areas for them.

Red-throated Diver. Photo: Chris Gomersall

While the finer details about the Wexford SPA have yet to come to light, it is clear that certain activities will not be permitted in the Wexford SPA. The Minister has issued a Direction in relation to certain activities, which must not be carried out within or close to the SPA, unless consent is lawfully given. The listed activities are reclamation including infilling; blasting, drilling, dredging or otherwise disturbing or removing fossils, rock, minerals, mud, sand, gravel or other sediment; introduction or reintroduction of plants or animals not found in the area; scientific research which involves the removal of biological material; any activity intended to disturb birds; undertaking acoustic surveys in the marine environment and developing or consenting to the development or operation of commercial recreational/ visitor facilities or organised recreational activities.

Little Terns.

Together with our partners at Fair Seas – a coalition of Ireland’s leading environmental NGOs and environmental networks of which BirdWatch Ireland is a founding member – we have been calling for the government to meet their targets, but this alone is not enough. More action must be taken in order for us to adequately protect these important marine habitats and the many species that they support. Any move to better protect important habitats for birds is to be welcomed, and this is certainly no different. We are urging the Irish government to be ambitious in their plans for this new SPA and stress the need for focused community engagement in the surrounding areas. We also continue our urgent calls for the publication of the long-awaited Marine Protected Areas (MPA) Bill.

Public support for ocean action swells as Fair Seas coalition continues to build momentum

Rosalind Skillen

The next few months of 2024 could be the most important yet for the Fair Seas campaign.

The MPA Bill has still not been published, with several deadlines for publishing the Bill missed last year, and the Government is in danger of running out of time to get this important legislation across the line.

While we wait for the MPA Bill to be released, BirdWatch Ireland, as part of the Fair Seas coalition, continues to build public and political support for ocean action. Having gathered more than 11,000 Irish signatures in under 4 weeks, the overwhelming support for our petition – urging the Irish government to release the MPA legislation without delay – demonstrates the huge appetite for effective marine protection. Our petition is still live at https://only.one/act/30x30-ireland, and we would encourage you to sign and share it if you have not done so already.

Black-legged Kittiwake. Photo: Colum Clarke.

Despite the hold-up of the MPA legislation, there has been some progress towards meeting Ireland’s targets of protecting 30% of Ireland’s seas by 2030. The New Year started on a high with Minister Noonan announcing the 'Seas off Wexford' special protection area, larger than Co. Wexford itself. These waters provide important food sources for seabirds, including Red-listed species such as Puffin and Kittiwake, and many other Amber-listed species such as Fulmar, Manx Shearwater and Shag. At 305,000 hectares, this new designation increases the percentage of Ireland’s marine protected waters to 9.4%, just under the 2025 target of 10%. In 2024, Fair Seas will continue to increase the public momentum and mass mobilisation for Marine Protected Area legislation by building on the events and activities of last year. Here are some events to look out for over the next few months:- BirdWatch Ireland have organised a series of talks on marine protection in collaboration with local branches, including in Cork, Sligo, Limerick, and Dublin. Make sure to stay updated with our range of events across the country via our newsletter and social media.

- Fair Seas are supporting Ken O’Sullivan’s series of ‘Into the Deep’ speaking tour across Ireland, as he recounts his adventures with marine mammals in the North Atlantic ocean. The second phase of the tour will take place in February 2024 across locations like Dublin, Wicklow, Waterford, and Donegal.

- There will also be an in-person film screening of the award-winning Fair Seas film ‘The Atlantic Northwest’ in Donegal on the 7th February. Come along to hear from anglers, divers, seafood producers and local people on what the ocean means to them.

Fair Seas 30x30

With EU and local elections looming in June, as well as the possibility of an Autumn General Election, the risk of the MPA legislation not being passed with this Government has never been higher. The urgency of the Bill progressing in the Oireachtas is paramount, and with your support, Fair Seas is in a strong position to influence the next steps of the MPA legislation. To all our members, allies, and friends: thank you for your support on the journey towards strong marine protection, and for your commitment to securing healthy seas for our future.