Sandwich Tern

| Irish Name: | Geabhróg scothdhubh |

| Scientific name: | Sterna sandvicensis |

| Bird Family: | Terns |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

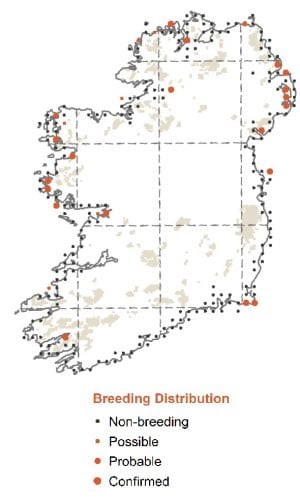

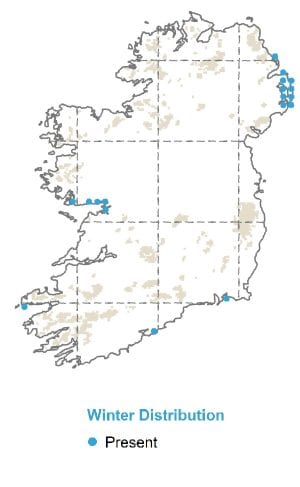

Summer visitor to all Irish coasts from March to September. Winters in small numbers in Galway Bay and Strangford Lough.

Identification

Usually seen over the sea. Relatively slender seabird with narrow, pointed wings, long, forked tail and long, pointed bill. Grey above and white below, dark cap to head. Flight light and buoyant, will hover briefly over the sea before diving in. The largest of the terns in Ireland, similar in size to Black-headed Gull. Told from other terns by its size and longer bill. Has a small yellow tip to its dark bill, which at closer quarters confirms identification. Distinct dark wedge to wing tip. Winter plumage, like all terns is different from breeding plumage, a white forehead develops in June/July. Juvenile plumage different from adult plumage with barred upperparts and darker wings.

Voice

A loud grating call, heard from colonies and whilst in flight.

Diet

Mainly surface dwelling fish, taken from shallow dive.

Breeding

Nest colonially on the ground, mainly on the coast but with some colonies inland. Nests on islands, shingle spits and sand dunes. Populations of colonies fluctuate dramatically between years. Present in Ireland from March to September, with occasional winter records

Wintering

Winters in southern Europe and Africa. Irish breeders have been recorded as far away as the Indian Ocean. About 10 to 15 birds winter in Galway Bay and Strangford Lough.

Monitored by

All-Ireland tern survey in 1995. Breeding seabirds are also monitored through breeding seabird surveys carried out every 15-20 years. Sandwich Terns are also monitored annually at Lady’s Island Lake.

Blog posts about this bird

Devastating Bird Flu impacts on Irish seabirds revealed in new study

A new study has revealed the devastating toll of the 2023 bird flu outbreak on Ireland’s tern species at their most important colonies, with Common Terns in particular suffering huge losses.

The recent highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 outbreak was the worst ever seen in Ireland, the UK and Europe. Details of the 2023 outbreak in Ireland, the number of birds that died at key breeding colonies, and the effect it has had on nesting numbers in 2024, have been published in the journal Bird Study by staff of BirdWatch Ireland and the National Parks and Wildlife Service. It focuses on colonies in Dublin (Rockabill Island, Dublin Port, Dalkey Island) and Wexford (Lady’s Island Lake) which have been subject to successful conservation efforts for decades, and the bird flu outbreak has come as a huge setback.

The full study entitled "A case study of the 2023 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak in tern (Sternidae) colonies on the east coast of the Republic of Ireland" was published in the journal Bird Study and can be accessed here.

A BirdWatch Ireland Tern Warden removes dead birds during the 2023 avian flu outbreak.

Common Terns suffered very high mortality across all colonies in 2023, with over 700 adult birds and over 1,100 chicks found dead by wardens in colonies at Rockabill, Dublin Port and Lady’s Island Lake. Many more will have died at sea and elsewhere along the coast and not been found, and a census of nests this year recorded a devastating loss of 1,250 breeding pairs across the colonies. In the case of Dublin Port, the colony was halved in a single year, representing the lowest number of nests in 19 years, and similarly the lowest on Rockabill Island since 2003. “The experience of visiting the colony during the outbreak and seeing so many dead and dying birds was really difficult,” said Helen Boland, manager of the Dublin Bay Birds Project. "We’re used to visiting the colony when it’s full of life, so to see so many lost in such a short space of time really had us worried about the future of the species. Terns are long-lived birds that only lay a small number of eggs per year, so losing adult birds is much more damaging to the population than having a bad breeding season.”Arctic Tern. Photo: Kevin Murphy

Arctic Terns were down by 160 breeding pairs, a 20% decline, across the colonies this year due to avian flu. The small colony at Dalkey Island suffered complete breeding failure early in summer 2023 due to rat predation, and this appears to have saved them from contracting avian flu as the birds had deserted before the virus reached Ireland. Arctic Terns lead a very challenging life, not just when trying to find safe places to nest on the Irish coast, but they migrate to Antarctica in the winter – a round trip of nearly 100,000km per year. They have been struggling to nest successfully at some key colonies in recent years, largely due to predation. This, coupled with the fact that Arctic Terns lay fewer eggs than Common Terns, means their recovery is expected to be much slower. Ireland holds 95% of the entire European population of the rare Roseate Tern, concentrated at Rockabill island in Dublin and Lady’s Island Lake in Wexford. Having so many birds at only two sites makes them particularly vulnerable to problems like disease, and their only colony in Britain had already been hit by bird flu in both 2022 and 2023. Despite 65 adult birds and 135 chicks being found dead in Irish colonies during the 2023 outbreak, this didn’t translate into significant losses this year; Lady’s Island was down by 31 pairs, but Rockabill managed to increase by 75 pairs. “The Roseate Tern numbers this year were a pleasant surprise and higher than we expected considering the losses we know came from avian flu,” said Dr. Steve Newton, BirdWatch Ireland’s Senior Seabird Conservationist. “It seems that the high number of chicks fledged in recent years means that recruitment of young birds into the colony was higher than the number of birds lost to bird flu. We’re still expecting to see slow or stalled population growth in the next few years, but it could have been much worse for the Roseates." The Sandwich Tern is Ireland’s largest species of tern, and over 1,500 pairs nest in Wexford. Sandwich Tern colonies all over the UK and Europe were hit with avian flu in 2022, but the virus didn’t reach Irish colonies that year. Nesting numbers last year indicate that Irish Sandwich Terns had suffered mortality on migration and in the wintering grounds however, with a loss of 300 pairs. It is assumed the remaining birds had developed some level of immunity to the virus and therefore escaped summer 2023 relatively unscathed, and actually bounced back to pre-flu numbers this year. This provides some encouragement that the birds can bounce back quickly, though it may simply be that the increase in birds is a result of immigration from other colonies.

Roseate Terns: Photo: Brian Burke.

Conservation staff of BirdWatch Ireland and NPWS began summer 2024 with a sense of trepidation that bird flu might return, but thankfully there were no signs of it in any of the colonies and most managed to have a successful breeding season this year. With only half the number of nesting pairs it had in 2023, the Dublin Port Tern colony had its most successful breeding season ever, with most pairs managing to fledge two chicks. Elsewhere, Roseate Terns at Rockabill did well, fledging at least one chick on average per pair. The Common Terns at Rockabill, and all tern species at Lady’s Island fared ok but generally faced problems with predation by gulls and foxes, amongst other species, and their greatly reduced numbers may have left them more vulnerable to predation. The long-term tern conservation work by BirdWatch Ireland and the National Parks and Wildlife Service, and long-term support from Dublin Port Company, mean we are well-placed to facilitate recovery at the east coast tern colonies, but avian flu likely impacted west-coast and inland tern sites too. The colonies discussed here are the most important ones nationally for these four tern species and the impact of avian flu emphasizes the importance of not having ‘all of our eggs in one basket’. BirdWatch Ireland’s new Strategy outlines our intention to expand our work to inland and west-coast tern colonies and help secure the status of these species all over the country. Despite calls from BirdWatch Ireland, the Republic of Ireland has yet to develop a formalised plan for the monitoring and management of HPAI in wild birds. The role of various state agencies in such an outbreak is not clear, with some seemingly prioritizing impacts on livestock, others on potential public health implications, but little in the way of monitoring and managing the impact on wild birds. In the absence of comprehensive guidelines, regular meetings between BirdWatch Ireland and the NPWS proved invaluable in 2023. These meetings facilitated a comprehensive and adaptive approach as new guidance emerged from authorities in the UK and Europe and as the HPAI situation developed. It also allowed for a range of precautions to be implemented to minimise the risk of spreading the virus within or between colonies, or to people, while maintaining conservation efforts and long-term monitoring. This paper makes several key recommendations for future HPAI management and procedures in Ireland. It calls for the establishment of a more direct relationship between DAFM, NPWS and BirdWatch Ireland to allow for a more strategic response to outbreaks; the clarification of roles and responsibilities across all relevant government bodies; better resourcing to manage outbreaks and an increase in annual monitoring at Irish seabird colonies wherever possible to help ensure that threats such as HPAI can be monitored in real-time. It is vital that changes are enacted without delay, not only to prevent future seabird losses in the 2025 breeding season, but also to protect the many waterbird species that winter in Ireland and are too at serious risk from HPAI. Despite two cases of avian flu in Little Terns in Ireland, the species escaped largely unscathed and almost all colonies reported increased nesting numbers in 2024. We will report on the Little Tern breeding season in the coming weeks.The full study entitled "A case study of the 2023 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak in tern (Sternidae) colonies on the east coast of the Republic of Ireland" was published in the journal Bird Study and can be accessed here.

The Rockabill Tern conservation project is a joint project between the National Parks & Wildlife Service and BirdWatch Ireland. https://www.npws.ie/

The Dublin Port Tern Conservation project is funded by Dublin Port Company as part of BirdWatch Ireland's 'Dublin Bay Birds Project'. https://www.dublinport.ie/

The Tern conservation project at Lady's Island Lake is a National Parks & Wildlife Service project, delivered by BirdWatch Ireland after a competitive tender process. https://www.npws.ie/

New protected area off Wexford coast is a step forward for vulnerable seabirds

The recent announcement of the new “Seas off Wexford” Special Protection Area (SPA) is certainly news to be welcomed.

For such a designation to be as effective as it can be, it is crucial that strong and effective conservation objectives and management plans are ambitious and that stakeholders are consulted throughout the process. It would be most welcome if the designation of new marine SPAs also led to a new vision for management of Ireland’s entire network of SPAs. BirdWatch Ireland calls on government to ensure that management plans are put in place for SPAs on both land and sea and that a whole-of-government approach is taken to implement them properly to safeguard the future of the birds they are intended to protect.

Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage Darragh O’Brien recently designated the new SPA of marine waters off the coast of Wexford which, at over 305,000 hectares, is the largest SPA designated in the history of the state. These waters provide extremely important food sources for seabirds, including Red-listed species such as Puffin, Kittiwake, Common Scoter and many other vulnerable Amber-listed species such as Fulmar, Manx Shearwater, Shag, Cormorant, Black-headed Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull, Herring Gull, Roseate Tern, Red-throated Diver, Gannet, Common Tern, Little Tern, Sandwich Tern, Mediterranean Gull and Guillemot.

Kittiwake. Photo: Colum Clarke.

Under EU legislation, the Irish government has made a commitment to designate 10% of its waters as protected by 2025, and a total of 30% by 2030. This new designation increases the percentage of Ireland’s marine protected waters to 9.4%, just under the 2025 target. While this is certainly a step in the right direction, many questions remain, primarily, what will “protection” look like in practice? It is paramount that this is made clear in the soon-to-be-published SPA’s conservation objectives, which should detail the activities that will and will not be permitted in the SPA, among other measures. We look forward to reading them shortly. At the same time, BirdWatch Ireland in collaboration with BirdLife Europe and BirdLife International are mapping Ireland’s marine Important Bird Areas according to international and standardised BirdLife International criteria under a project funded by the Flotilla Foundation. This is an important time for our seabirds and it is welcome to see the government’s focus finally on setting out protected areas for them.

Red-throated Diver. Photo: Chris Gomersall

While the finer details about the Wexford SPA have yet to come to light, it is clear that certain activities will not be permitted in the Wexford SPA. The Minister has issued a Direction in relation to certain activities, which must not be carried out within or close to the SPA, unless consent is lawfully given. The listed activities are reclamation including infilling; blasting, drilling, dredging or otherwise disturbing or removing fossils, rock, minerals, mud, sand, gravel or other sediment; introduction or reintroduction of plants or animals not found in the area; scientific research which involves the removal of biological material; any activity intended to disturb birds; undertaking acoustic surveys in the marine environment and developing or consenting to the development or operation of commercial recreational/ visitor facilities or organised recreational activities.

Little Terns.

Together with our partners at Fair Seas – a coalition of Ireland’s leading environmental NGOs and environmental networks of which BirdWatch Ireland is a founding member – we have been calling for the government to meet their targets, but this alone is not enough. More action must be taken in order for us to adequately protect these important marine habitats and the many species that they support. Any move to better protect important habitats for birds is to be welcomed, and this is certainly no different. We are urging the Irish government to be ambitious in their plans for this new SPA and stress the need for focused community engagement in the surrounding areas. We also continue our urgent calls for the publication of the long-awaited Marine Protected Areas (MPA) Bill.