Black-headed Gull

| Irish Name: | Sléibhín |

| Scientific name: | Larus ridibundus |

| Bird Family: | Gulls |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

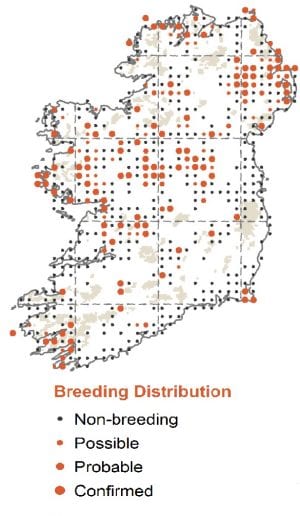

Resident along all Irish coasts, with significant numbers arriving from the Continent in winter. Breeds in small numbers on islands in larger lakes in western Ireland.

Identification

A small gull, slightly smaller than Common Gull. Adults are pale grey above and white below. Adults are easily told apart from other Common Gull species by the thick white leading edge to outer wing, which can be seen at some distance. A blackish area bordering the white leading edge of the underwing is also evident. Pointed wings, and a small tail and head in proportion to the body, along with a long neck give a distinctive profile compared to other gulls. Adults have red legs, and in summer plumage, a dark brown hood on the head; in the winter, the hood in absent and is replaced by a dark spot behind the eye. Black-headed Gulls have two age groups, and attains adult plumage after one year when it moults into adult winter plumage. Young birds just out of the nest are finely patterned on the upperparts in ginger and brown and show a black tail band. First winter and first summer birds retain the wing and tail markings of the juvenile bird, but show grey on the mantle and in the first summer, a hood with a variable amount of white mixed in with the brown. Just after the bird is one year old it moults into adult winter plumage.

Voice

Strident, down slurred call. Can be very noisy at colonies.

Diet

Feeds on insects especially in arable fields. Will also exploit domestic and fisheries waste.

Breeding

Breeds both on the coast and inland where they will often nest in colonies. Usually, nests on the ground in wetland areas, such as bogs and marshes and will also use man made lakes. Numbers breeding inland have declined dramatically, probably due to predation by the American Mink, which is an able swimmer and is able to access previously inaccessible nesting areas. The largest colonies in Ireland are in Northern Ireland on Lough Neagh. Colonies in the Republic are not widespread, the largest are found inland in Counties Galway, Monaghan and Mayo and at coastal sites in Counties Wexford and Donegal

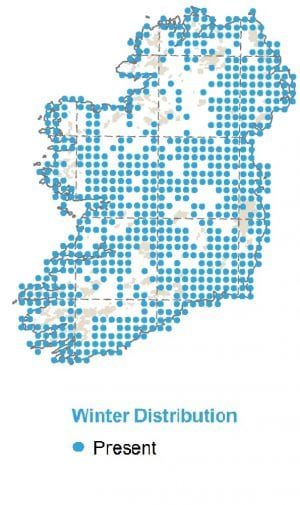

Wintering

Irish birds are augmented by wintering birds from northern and eastern Europe and are widespread on both on the coast and inland.

Monitored by

Wintering birds are monitored through the Irish Wetland Bird Survey. Breeding seabirds are monitored through breeding seabird surveys carried out every 15-20 years.

Blog posts about this bird

New protected area off Wexford coast is a step forward for vulnerable seabirds

The recent announcement of the new “Seas off Wexford” Special Protection Area (SPA) is certainly news to be welcomed.

For such a designation to be as effective as it can be, it is crucial that strong and effective conservation objectives and management plans are ambitious and that stakeholders are consulted throughout the process. It would be most welcome if the designation of new marine SPAs also led to a new vision for management of Ireland’s entire network of SPAs. BirdWatch Ireland calls on government to ensure that management plans are put in place for SPAs on both land and sea and that a whole-of-government approach is taken to implement them properly to safeguard the future of the birds they are intended to protect.

Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage Darragh O’Brien recently designated the new SPA of marine waters off the coast of Wexford which, at over 305,000 hectares, is the largest SPA designated in the history of the state. These waters provide extremely important food sources for seabirds, including Red-listed species such as Puffin, Kittiwake, Common Scoter and many other vulnerable Amber-listed species such as Fulmar, Manx Shearwater, Shag, Cormorant, Black-headed Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull, Herring Gull, Roseate Tern, Red-throated Diver, Gannet, Common Tern, Little Tern, Sandwich Tern, Mediterranean Gull and Guillemot.

Kittiwake. Photo: Colum Clarke.

Under EU legislation, the Irish government has made a commitment to designate 10% of its waters as protected by 2025, and a total of 30% by 2030. This new designation increases the percentage of Ireland’s marine protected waters to 9.4%, just under the 2025 target. While this is certainly a step in the right direction, many questions remain, primarily, what will “protection” look like in practice? It is paramount that this is made clear in the soon-to-be-published SPA’s conservation objectives, which should detail the activities that will and will not be permitted in the SPA, among other measures. We look forward to reading them shortly. At the same time, BirdWatch Ireland in collaboration with BirdLife Europe and BirdLife International are mapping Ireland’s marine Important Bird Areas according to international and standardised BirdLife International criteria under a project funded by the Flotilla Foundation. This is an important time for our seabirds and it is welcome to see the government’s focus finally on setting out protected areas for them.

Red-throated Diver. Photo: Chris Gomersall

While the finer details about the Wexford SPA have yet to come to light, it is clear that certain activities will not be permitted in the Wexford SPA. The Minister has issued a Direction in relation to certain activities, which must not be carried out within or close to the SPA, unless consent is lawfully given. The listed activities are reclamation including infilling; blasting, drilling, dredging or otherwise disturbing or removing fossils, rock, minerals, mud, sand, gravel or other sediment; introduction or reintroduction of plants or animals not found in the area; scientific research which involves the removal of biological material; any activity intended to disturb birds; undertaking acoustic surveys in the marine environment and developing or consenting to the development or operation of commercial recreational/ visitor facilities or organised recreational activities.

Little Terns.

Together with our partners at Fair Seas – a coalition of Ireland’s leading environmental NGOs and environmental networks of which BirdWatch Ireland is a founding member – we have been calling for the government to meet their targets, but this alone is not enough. More action must be taken in order for us to adequately protect these important marine habitats and the many species that they support. Any move to better protect important habitats for birds is to be welcomed, and this is certainly no different. We are urging the Irish government to be ambitious in their plans for this new SPA and stress the need for focused community engagement in the surrounding areas. We also continue our urgent calls for the publication of the long-awaited Marine Protected Areas (MPA) Bill.

Red Alert - Irish Garden Birds of Conservation Concern

This year the ‘Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland’ list was updated based on the most recent data and research available. The list is a joint publication by BirdWatch Ireland and our colleagues in RSPB Northern Ireland. You might be forgiven for thinking that it’s a list of rare birds, some of which you mightn’t have even heard of, restricted to remote islands or patches of pristine habitat that you’d have to drive and hike hours to get to. The reality is though, you’d recognise most of the species on the list, they probably occur much closer than you might think, and there’s a very good chance you’ll have some red and amber-listed bird species in your garden this winter!

The list utilises a traffic-light colour system to highlight species that we need to be worried about. There are a number of ways a species can make it onto the red list (top concern) or Amber List (medium concern), and it’s not solely based on low numbers. If you wait until a bird is down to a hundred pairs or less it might already be too late to save it, so as well as total numbers or breeding pairs we also examine the population trend. Whether a species is widespread or not, if we see that it’s declining by a large amount in a relatively short space of time, then it’s clearly in need of some attention. In addition, we consider the international picture. If a species is stable in Ireland but undergoing serious declines in other countries, then that sounds the alarm bell for us to keep an eye on the Irish population, and it also means the Irish population is of increased importance.

See below for a list of birds that are on the red and Amber List of conservation concern in Ireland, that are also recorded in gardens every winter through the Irish Garden Bird Survey. In the case of some, you’ll likely be thinking “well we have plenty of them here” but bear in mind this is based on the picture across Ireland (ROI and NI) as a whole. You might be lucky enough to have some of these birds in good numbers, but the wider picture across Ireland and Europe might be worse than you think.

Starling – Amber List (79% of Irish Gardens)

Starlings are doing ok in Ireland, but we’re one of very few countries who can say that. They’re on the Irish Amber List due to declines over the majority of their European range. If they’re bothering you by nesting in your eaves every summer, now is a good time to put out a nestbox with a large hole and block up any gaps in your gutters to ensure they nest where you want them to nest. Don’t forget these are the birds responsible for one of nature’s greatest spectacles, their winter murmurations! If you see a Starling murmurations this winter, please let us know by logging it here.

Starling – Amber List (79% of Irish Gardens)

Starlings are doing ok in Ireland, but we’re one of very few countries who can say that. They’re on the Irish Amber List due to declines over the majority of their European range. If they’re bothering you by nesting in your eaves every summer, now is a good time to put out a nestbox with a large hole and block up any gaps in your gutters to ensure they nest where you want them to nest. Don’t forget these are the birds responsible for one of nature’s greatest spectacles, their winter murmurations! If you see a Starling murmurations this winter, please let us know by logging it here.

House Sparrow – Amber List (84% of Irish Gardens)

House Sparrows have an unfavourable conservation status in Europe, so are amber-listed here. Their numbers are doing ok in Ireland, though it’s likely that they have lost much nesting habitat that they historically had in towns and villages due to new more efficient building methods. They’ll happily eat peanuts, sunflower seeds and more in Irish gardens, and you can give them an extra helping hand by providing them with a nestbox. Unlike Blue Tits and Great Tits which are territorial nesters, House Sparrows nest in loose colonies, so you can buy a ‘terraced’ nestbox and possibly get 2 or 3 pairs nesting as neighbours. In the Irish Garden Bird Survey, they’re very much an ‘all or nothing’ species, so you either won’t have any each winter, or you’ll have flocks of 10 or more! Some people refer to them as ‘hedge sparrows’, which is understandable given their behaviour, but that name is also often given to a completely different species (Dunnock), so please make sure to log these as ‘House Sparrows’ in your survey.

House Sparrow – Amber List (84% of Irish Gardens)

House Sparrows have an unfavourable conservation status in Europe, so are amber-listed here. Their numbers are doing ok in Ireland, though it’s likely that they have lost much nesting habitat that they historically had in towns and villages due to new more efficient building methods. They’ll happily eat peanuts, sunflower seeds and more in Irish gardens, and you can give them an extra helping hand by providing them with a nestbox. Unlike Blue Tits and Great Tits which are territorial nesters, House Sparrows nest in loose colonies, so you can buy a ‘terraced’ nestbox and possibly get 2 or 3 pairs nesting as neighbours. In the Irish Garden Bird Survey, they’re very much an ‘all or nothing’ species, so you either won’t have any each winter, or you’ll have flocks of 10 or more! Some people refer to them as ‘hedge sparrows’, which is understandable given their behaviour, but that name is also often given to a completely different species (Dunnock), so please make sure to log these as ‘House Sparrows’ in your survey.

Greenfinch – Amber List (72% of Irish Gardens)

The Greenfinch breeding population has declined by a whopping 48% in recent years. This won’t come as any surprise to BirdWatch Ireland members and regular Irish Garden Bird Survey participants. The blame can be laid solely at the feet of the trichomonas parasite, and this is the reason that you should give all of your feeders a good cleaning at least once a week if not more, during the winter. Greenfinches were one of the most common garden birds in Ireland in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s but since trichomoniasis took hold, their numbers have been in freefall. They are now on the red list in Britain for the same reason. For more information about trichomoniasis, how to spot a sick bird, and what you should do, read here.

Greenfinch – Amber List (72% of Irish Gardens)

The Greenfinch breeding population has declined by a whopping 48% in recent years. This won’t come as any surprise to BirdWatch Ireland members and regular Irish Garden Bird Survey participants. The blame can be laid solely at the feet of the trichomonas parasite, and this is the reason that you should give all of your feeders a good cleaning at least once a week if not more, during the winter. Greenfinches were one of the most common garden birds in Ireland in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s but since trichomoniasis took hold, their numbers have been in freefall. They are now on the red list in Britain for the same reason. For more information about trichomoniasis, how to spot a sick bird, and what you should do, read here.

Goldcrest – Amber List (30% of Irish Gardens)

Their numbers are stable in Ireland, though as our smallest bird they’re extremely vulnerable to periods of cold weather and declines at European level mean they’re on our Amber list. As an insectivore, there isn’t anything you can put in your feeders for them but consider this good motivation to plant trees and shrubs in your garden and maintain a ‘wild patch’ wherever you can. Their conservation status in Europe is ‘unfavourable’, hence their amber listing.

Goldcrest – Amber List (30% of Irish Gardens)

Their numbers are stable in Ireland, though as our smallest bird they’re extremely vulnerable to periods of cold weather and declines at European level mean they’re on our Amber list. As an insectivore, there isn’t anything you can put in your feeders for them but consider this good motivation to plant trees and shrubs in your garden and maintain a ‘wild patch’ wherever you can. Their conservation status in Europe is ‘unfavourable’, hence their amber listing.

Redwing – Red List (17% of Irish Gardens)

Redwing were previously on the green list, but due to declines at international level have now moved to the Irish red list. Redwings migrate to Ireland from Iceland, Scandinavia and northern Europe from October onwards, and are more likely to turn up in gardens where there are berries on trees and bushes, or where fruit such as apples and pears are provided. There is always an increase in records during frosty and snowy weather each winter. Loss of nesting habitat and climate change have been implicated in their decline.

Redwing – Red List (17% of Irish Gardens)

Redwing were previously on the green list, but due to declines at international level have now moved to the Irish red list. Redwings migrate to Ireland from Iceland, Scandinavia and northern Europe from October onwards, and are more likely to turn up in gardens where there are berries on trees and bushes, or where fruit such as apples and pears are provided. There is always an increase in records during frosty and snowy weather each winter. Loss of nesting habitat and climate change have been implicated in their decline.

Grey Wagtail – Red List (12% of Irish Gardens)

Grey Wagtails are often reported as Yellow Wagtails in the Irish Garden Bird Survey, because their most noticeable colour is yellow (but Yellow Wagtail is a different, much more yellow species!). Though they’re a river-nesting species, they’re not afraid to visit gardens for food during winter and are particularly attracted to gardens with small ponds or streams. Being heavily reliant on insect prey, Grey Wagtail numbers decline rapidly if we have a winter with a few frosty or snowy days, and we saw this after the cold winters of 2010/11 and 2011/12, as well as the ‘Beast from the East’ a few years ago. Grey Wagtail breeding numbers and range have declined by 50% in Ireland in the short term, and this year’s cold spring and early summer is unlikely to have done them any favours. Do be careful not to confuse the Grey Wagtail with the more common Pied Wagtail (which is black and white and grey, confusingly!).

Grey Wagtail – Red List (12% of Irish Gardens)

Grey Wagtails are often reported as Yellow Wagtails in the Irish Garden Bird Survey, because their most noticeable colour is yellow (but Yellow Wagtail is a different, much more yellow species!). Though they’re a river-nesting species, they’re not afraid to visit gardens for food during winter and are particularly attracted to gardens with small ponds or streams. Being heavily reliant on insect prey, Grey Wagtail numbers decline rapidly if we have a winter with a few frosty or snowy days, and we saw this after the cold winters of 2010/11 and 2011/12, as well as the ‘Beast from the East’ a few years ago. Grey Wagtail breeding numbers and range have declined by 50% in Ireland in the short term, and this year’s cold spring and early summer is unlikely to have done them any favours. Do be careful not to confuse the Grey Wagtail with the more common Pied Wagtail (which is black and white and grey, confusingly!).

Linnet – Amber List (10% of Irish Gardens)

Linnets are amber-listed due to declines at European level. Over the last 20 years or so they’ve undergone a moderate increase in Ireland and have regained some of the ground lost due to changing agricultural practices in the 1970’s. Their numbers in the Irish Garden Bird Survey have increased in urban areas in recent years, with their occurrence in rural gardens remaining much the same.

Linnet – Amber List (10% of Irish Gardens)

Linnets are amber-listed due to declines at European level. Over the last 20 years or so they’ve undergone a moderate increase in Ireland and have regained some of the ground lost due to changing agricultural practices in the 1970’s. Their numbers in the Irish Garden Bird Survey have increased in urban areas in recent years, with their occurrence in rural gardens remaining much the same.

Herring Gull – Amber List (>8% of Irish Gardens)

Herring Gulls were previously red-listed, so it’s good that they’re now only amber-listed. This is one of our large gulls, and many reports we get of ‘seagulls’ and ‘common gulls’ every winter likely relate to this species instead. Though their status has improved, their breeding population has declined by 29% in the short-term and 50% in the long-term, so they have a long way to go to get back to their former numbers. The loss of breeding habitat that has impacted them isn’t unique to Ireland and they have an unfavourable conservation status at a wider European level too.

Herring Gull – Amber List (>8% of Irish Gardens)

Herring Gulls were previously red-listed, so it’s good that they’re now only amber-listed. This is one of our large gulls, and many reports we get of ‘seagulls’ and ‘common gulls’ every winter likely relate to this species instead. Though their status has improved, their breeding population has declined by 29% in the short-term and 50% in the long-term, so they have a long way to go to get back to their former numbers. The loss of breeding habitat that has impacted them isn’t unique to Ireland and they have an unfavourable conservation status at a wider European level too.

Black-headed Gull – Amber List (>5% of Irish Gardens)

The Black-headed Gull is one of the more positive stories here, given that it was previously on the red list but was downgraded to the Amber List this year. They’re recent history includes moderate breeding range declines of 55% in the short term and 55% in the long-term, so they’re not out of the woods yet, but it’s good that they’re improving. If you have a small-ish gull, around the size of a Jackdaw or Magpie, visiting your garden then it’s more than likely a Black-headed Gull. They’re reported from 5% of gardens each winter, but we also get records of ‘seagulls’ and ‘common gulls’ which are likely a mix of Black-headed Gulls and their larger cousin the Herring Gull.

Black-headed Gull – Amber List (>5% of Irish Gardens)

The Black-headed Gull is one of the more positive stories here, given that it was previously on the red list but was downgraded to the Amber List this year. They’re recent history includes moderate breeding range declines of 55% in the short term and 55% in the long-term, so they’re not out of the woods yet, but it’s good that they’re improving. If you have a small-ish gull, around the size of a Jackdaw or Magpie, visiting your garden then it’s more than likely a Black-headed Gull. They’re reported from 5% of gardens each winter, but we also get records of ‘seagulls’ and ‘common gulls’ which are likely a mix of Black-headed Gulls and their larger cousin the Herring Gull.

Yellowhammer – Red List (5% of Irish Gardens)

Yellowhammer have declined by 50% in Ireland since the 1980’s, their breeding range has declined by 61% over a similar period, and they have an unfavourable conservation status in Europe, all due to changes in agriculture in Ireland and further afield. This means they’re very firmly placed on the red list. In the winter they enjoy seeds spread on the ground, and are most often reported in counties in Leinster, arriving into gardens with finch and sparrow flocks. Lack of food during the winter months is known to be a factor limiting their numbers, so if you have visiting Yellowhammers, you’re doing them a real favour by keeping your feeders filled, particularly in January, February and into March.

Yellowhammer – Red List (5% of Irish Gardens)

Yellowhammer have declined by 50% in Ireland since the 1980’s, their breeding range has declined by 61% over a similar period, and they have an unfavourable conservation status in Europe, all due to changes in agriculture in Ireland and further afield. This means they’re very firmly placed on the red list. In the winter they enjoy seeds spread on the ground, and are most often reported in counties in Leinster, arriving into gardens with finch and sparrow flocks. Lack of food during the winter months is known to be a factor limiting their numbers, so if you have visiting Yellowhammers, you’re doing them a real favour by keeping your feeders filled, particularly in January, February and into March.

Tree Sparrow – Amber List (5% of Irish Gardens)

Tree Sparrows are much more of a farmland specialist than the House Sparrow and are declining across much of Europe. They’re a species largely confined to Leinster, like the Yellowhammer, and like they Yellowhammer they declined a lot as Irish agricultural practices shifted in the 1970s and afterwards. Tree Sparrows are still quite scarce over much of the country, but there are some signs that they’re not doing as bad as they once were and are possibly gaining a little bit of ground in the Irish countryside again.

Tree Sparrow – Amber List (5% of Irish Gardens)

Tree Sparrows are much more of a farmland specialist than the House Sparrow and are declining across much of Europe. They’re a species largely confined to Leinster, like the Yellowhammer, and like they Yellowhammer they declined a lot as Irish agricultural practices shifted in the 1970s and afterwards. Tree Sparrows are still quite scarce over much of the country, but there are some signs that they’re not doing as bad as they once were and are possibly gaining a little bit of ground in the Irish countryside again.

Brambling – Amber List (4% of Irish Gardens)

Brambling is a species of finch that doesn’t breed here and only occurs here in very small numbers each winter, and their listing is therefore due to declines at European level rather than anything here in Ireland. Keep an eye out with them amongst your visiting Chaffinches – they look quite similar and have similar feeding habitats, and they’ll likely only hang around for a couple of weeks, returning to Scandinavia and northern Europe in the latter stages of the winter.

Brambling – Amber List (4% of Irish Gardens)

Brambling is a species of finch that doesn’t breed here and only occurs here in very small numbers each winter, and their listing is therefore due to declines at European level rather than anything here in Ireland. Keep an eye out with them amongst your visiting Chaffinches – they look quite similar and have similar feeding habitats, and they’ll likely only hang around for a couple of weeks, returning to Scandinavia and northern Europe in the latter stages of the winter.

Meadow Pipit – Red list (3% of Irish Gardens)

Meadow Pipit too are red listed due to significant declines at global level due to agricultural intensification. Their numbers have relatively stable in Ireland over the last twenty years, however. Though not a common garden species, we get a large spike in reports of Meadow Pipits when cold and frosty weather forces them to seek unfrozen ground for foraging. They’re a species whose numbers tend to decline rapidly after a cold winter, taking a couple of years to bounce back.

Meadow Pipit – Red list (3% of Irish Gardens)

Meadow Pipit too are red listed due to significant declines at global level due to agricultural intensification. Their numbers have relatively stable in Ireland over the last twenty years, however. Though not a common garden species, we get a large spike in reports of Meadow Pipits when cold and frosty weather forces them to seek unfrozen ground for foraging. They’re a species whose numbers tend to decline rapidly after a cold winter, taking a couple of years to bounce back.

Starling – Amber List (79% of Irish Gardens)

Starlings are doing ok in Ireland, but we’re one of very few countries who can say that. They’re on the Irish Amber List due to declines over the majority of their European range. If they’re bothering you by nesting in your eaves every summer, now is a good time to put out a nestbox with a large hole and block up any gaps in your gutters to ensure they nest where you want them to nest. Don’t forget these are the birds responsible for one of nature’s greatest spectacles, their winter murmurations! If you see a Starling murmurations this winter, please let us know by logging it here.

Starling – Amber List (79% of Irish Gardens)

Starlings are doing ok in Ireland, but we’re one of very few countries who can say that. They’re on the Irish Amber List due to declines over the majority of their European range. If they’re bothering you by nesting in your eaves every summer, now is a good time to put out a nestbox with a large hole and block up any gaps in your gutters to ensure they nest where you want them to nest. Don’t forget these are the birds responsible for one of nature’s greatest spectacles, their winter murmurations! If you see a Starling murmurations this winter, please let us know by logging it here.

House Sparrow – Amber List (84% of Irish Gardens)

House Sparrows have an unfavourable conservation status in Europe, so are amber-listed here. Their numbers are doing ok in Ireland, though it’s likely that they have lost much nesting habitat that they historically had in towns and villages due to new more efficient building methods. They’ll happily eat peanuts, sunflower seeds and more in Irish gardens, and you can give them an extra helping hand by providing them with a nestbox. Unlike Blue Tits and Great Tits which are territorial nesters, House Sparrows nest in loose colonies, so you can buy a ‘terraced’ nestbox and possibly get 2 or 3 pairs nesting as neighbours. In the Irish Garden Bird Survey, they’re very much an ‘all or nothing’ species, so you either won’t have any each winter, or you’ll have flocks of 10 or more! Some people refer to them as ‘hedge sparrows’, which is understandable given their behaviour, but that name is also often given to a completely different species (Dunnock), so please make sure to log these as ‘House Sparrows’ in your survey.

House Sparrow – Amber List (84% of Irish Gardens)

House Sparrows have an unfavourable conservation status in Europe, so are amber-listed here. Their numbers are doing ok in Ireland, though it’s likely that they have lost much nesting habitat that they historically had in towns and villages due to new more efficient building methods. They’ll happily eat peanuts, sunflower seeds and more in Irish gardens, and you can give them an extra helping hand by providing them with a nestbox. Unlike Blue Tits and Great Tits which are territorial nesters, House Sparrows nest in loose colonies, so you can buy a ‘terraced’ nestbox and possibly get 2 or 3 pairs nesting as neighbours. In the Irish Garden Bird Survey, they’re very much an ‘all or nothing’ species, so you either won’t have any each winter, or you’ll have flocks of 10 or more! Some people refer to them as ‘hedge sparrows’, which is understandable given their behaviour, but that name is also often given to a completely different species (Dunnock), so please make sure to log these as ‘House Sparrows’ in your survey.

Greenfinch – Amber List (72% of Irish Gardens)

The Greenfinch breeding population has declined by a whopping 48% in recent years. This won’t come as any surprise to BirdWatch Ireland members and regular Irish Garden Bird Survey participants. The blame can be laid solely at the feet of the trichomonas parasite, and this is the reason that you should give all of your feeders a good cleaning at least once a week if not more, during the winter. Greenfinches were one of the most common garden birds in Ireland in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s but since trichomoniasis took hold, their numbers have been in freefall. They are now on the red list in Britain for the same reason. For more information about trichomoniasis, how to spot a sick bird, and what you should do, read here.

Greenfinch – Amber List (72% of Irish Gardens)

The Greenfinch breeding population has declined by a whopping 48% in recent years. This won’t come as any surprise to BirdWatch Ireland members and regular Irish Garden Bird Survey participants. The blame can be laid solely at the feet of the trichomonas parasite, and this is the reason that you should give all of your feeders a good cleaning at least once a week if not more, during the winter. Greenfinches were one of the most common garden birds in Ireland in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s but since trichomoniasis took hold, their numbers have been in freefall. They are now on the red list in Britain for the same reason. For more information about trichomoniasis, how to spot a sick bird, and what you should do, read here.

Goldcrest – Amber List (30% of Irish Gardens)

Their numbers are stable in Ireland, though as our smallest bird they’re extremely vulnerable to periods of cold weather and declines at European level mean they’re on our Amber list. As an insectivore, there isn’t anything you can put in your feeders for them but consider this good motivation to plant trees and shrubs in your garden and maintain a ‘wild patch’ wherever you can. Their conservation status in Europe is ‘unfavourable’, hence their amber listing.

Goldcrest – Amber List (30% of Irish Gardens)

Their numbers are stable in Ireland, though as our smallest bird they’re extremely vulnerable to periods of cold weather and declines at European level mean they’re on our Amber list. As an insectivore, there isn’t anything you can put in your feeders for them but consider this good motivation to plant trees and shrubs in your garden and maintain a ‘wild patch’ wherever you can. Their conservation status in Europe is ‘unfavourable’, hence their amber listing.

Redwing – Red List (17% of Irish Gardens)

Redwing were previously on the green list, but due to declines at international level have now moved to the Irish red list. Redwings migrate to Ireland from Iceland, Scandinavia and northern Europe from October onwards, and are more likely to turn up in gardens where there are berries on trees and bushes, or where fruit such as apples and pears are provided. There is always an increase in records during frosty and snowy weather each winter. Loss of nesting habitat and climate change have been implicated in their decline.

Redwing – Red List (17% of Irish Gardens)

Redwing were previously on the green list, but due to declines at international level have now moved to the Irish red list. Redwings migrate to Ireland from Iceland, Scandinavia and northern Europe from October onwards, and are more likely to turn up in gardens where there are berries on trees and bushes, or where fruit such as apples and pears are provided. There is always an increase in records during frosty and snowy weather each winter. Loss of nesting habitat and climate change have been implicated in their decline.

Grey Wagtail – Red List (12% of Irish Gardens)

Grey Wagtails are often reported as Yellow Wagtails in the Irish Garden Bird Survey, because their most noticeable colour is yellow (but Yellow Wagtail is a different, much more yellow species!). Though they’re a river-nesting species, they’re not afraid to visit gardens for food during winter and are particularly attracted to gardens with small ponds or streams. Being heavily reliant on insect prey, Grey Wagtail numbers decline rapidly if we have a winter with a few frosty or snowy days, and we saw this after the cold winters of 2010/11 and 2011/12, as well as the ‘Beast from the East’ a few years ago. Grey Wagtail breeding numbers and range have declined by 50% in Ireland in the short term, and this year’s cold spring and early summer is unlikely to have done them any favours. Do be careful not to confuse the Grey Wagtail with the more common Pied Wagtail (which is black and white and grey, confusingly!).

Grey Wagtail – Red List (12% of Irish Gardens)

Grey Wagtails are often reported as Yellow Wagtails in the Irish Garden Bird Survey, because their most noticeable colour is yellow (but Yellow Wagtail is a different, much more yellow species!). Though they’re a river-nesting species, they’re not afraid to visit gardens for food during winter and are particularly attracted to gardens with small ponds or streams. Being heavily reliant on insect prey, Grey Wagtail numbers decline rapidly if we have a winter with a few frosty or snowy days, and we saw this after the cold winters of 2010/11 and 2011/12, as well as the ‘Beast from the East’ a few years ago. Grey Wagtail breeding numbers and range have declined by 50% in Ireland in the short term, and this year’s cold spring and early summer is unlikely to have done them any favours. Do be careful not to confuse the Grey Wagtail with the more common Pied Wagtail (which is black and white and grey, confusingly!).

Linnet – Amber List (10% of Irish Gardens)

Linnets are amber-listed due to declines at European level. Over the last 20 years or so they’ve undergone a moderate increase in Ireland and have regained some of the ground lost due to changing agricultural practices in the 1970’s. Their numbers in the Irish Garden Bird Survey have increased in urban areas in recent years, with their occurrence in rural gardens remaining much the same.

Linnet – Amber List (10% of Irish Gardens)

Linnets are amber-listed due to declines at European level. Over the last 20 years or so they’ve undergone a moderate increase in Ireland and have regained some of the ground lost due to changing agricultural practices in the 1970’s. Their numbers in the Irish Garden Bird Survey have increased in urban areas in recent years, with their occurrence in rural gardens remaining much the same.

Herring Gull – Amber List (>8% of Irish Gardens)

Herring Gulls were previously red-listed, so it’s good that they’re now only amber-listed. This is one of our large gulls, and many reports we get of ‘seagulls’ and ‘common gulls’ every winter likely relate to this species instead. Though their status has improved, their breeding population has declined by 29% in the short-term and 50% in the long-term, so they have a long way to go to get back to their former numbers. The loss of breeding habitat that has impacted them isn’t unique to Ireland and they have an unfavourable conservation status at a wider European level too.

Herring Gull – Amber List (>8% of Irish Gardens)

Herring Gulls were previously red-listed, so it’s good that they’re now only amber-listed. This is one of our large gulls, and many reports we get of ‘seagulls’ and ‘common gulls’ every winter likely relate to this species instead. Though their status has improved, their breeding population has declined by 29% in the short-term and 50% in the long-term, so they have a long way to go to get back to their former numbers. The loss of breeding habitat that has impacted them isn’t unique to Ireland and they have an unfavourable conservation status at a wider European level too.

Black-headed Gull – Amber List (>5% of Irish Gardens)

The Black-headed Gull is one of the more positive stories here, given that it was previously on the red list but was downgraded to the Amber List this year. They’re recent history includes moderate breeding range declines of 55% in the short term and 55% in the long-term, so they’re not out of the woods yet, but it’s good that they’re improving. If you have a small-ish gull, around the size of a Jackdaw or Magpie, visiting your garden then it’s more than likely a Black-headed Gull. They’re reported from 5% of gardens each winter, but we also get records of ‘seagulls’ and ‘common gulls’ which are likely a mix of Black-headed Gulls and their larger cousin the Herring Gull.

Black-headed Gull – Amber List (>5% of Irish Gardens)

The Black-headed Gull is one of the more positive stories here, given that it was previously on the red list but was downgraded to the Amber List this year. They’re recent history includes moderate breeding range declines of 55% in the short term and 55% in the long-term, so they’re not out of the woods yet, but it’s good that they’re improving. If you have a small-ish gull, around the size of a Jackdaw or Magpie, visiting your garden then it’s more than likely a Black-headed Gull. They’re reported from 5% of gardens each winter, but we also get records of ‘seagulls’ and ‘common gulls’ which are likely a mix of Black-headed Gulls and their larger cousin the Herring Gull.

Yellowhammer – Red List (5% of Irish Gardens)

Yellowhammer have declined by 50% in Ireland since the 1980’s, their breeding range has declined by 61% over a similar period, and they have an unfavourable conservation status in Europe, all due to changes in agriculture in Ireland and further afield. This means they’re very firmly placed on the red list. In the winter they enjoy seeds spread on the ground, and are most often reported in counties in Leinster, arriving into gardens with finch and sparrow flocks. Lack of food during the winter months is known to be a factor limiting their numbers, so if you have visiting Yellowhammers, you’re doing them a real favour by keeping your feeders filled, particularly in January, February and into March.

Yellowhammer – Red List (5% of Irish Gardens)

Yellowhammer have declined by 50% in Ireland since the 1980’s, their breeding range has declined by 61% over a similar period, and they have an unfavourable conservation status in Europe, all due to changes in agriculture in Ireland and further afield. This means they’re very firmly placed on the red list. In the winter they enjoy seeds spread on the ground, and are most often reported in counties in Leinster, arriving into gardens with finch and sparrow flocks. Lack of food during the winter months is known to be a factor limiting their numbers, so if you have visiting Yellowhammers, you’re doing them a real favour by keeping your feeders filled, particularly in January, February and into March.

Tree Sparrow – Amber List (5% of Irish Gardens)

Tree Sparrows are much more of a farmland specialist than the House Sparrow and are declining across much of Europe. They’re a species largely confined to Leinster, like the Yellowhammer, and like they Yellowhammer they declined a lot as Irish agricultural practices shifted in the 1970s and afterwards. Tree Sparrows are still quite scarce over much of the country, but there are some signs that they’re not doing as bad as they once were and are possibly gaining a little bit of ground in the Irish countryside again.

Tree Sparrow – Amber List (5% of Irish Gardens)

Tree Sparrows are much more of a farmland specialist than the House Sparrow and are declining across much of Europe. They’re a species largely confined to Leinster, like the Yellowhammer, and like they Yellowhammer they declined a lot as Irish agricultural practices shifted in the 1970s and afterwards. Tree Sparrows are still quite scarce over much of the country, but there are some signs that they’re not doing as bad as they once were and are possibly gaining a little bit of ground in the Irish countryside again.

Brambling – Amber List (4% of Irish Gardens)

Brambling is a species of finch that doesn’t breed here and only occurs here in very small numbers each winter, and their listing is therefore due to declines at European level rather than anything here in Ireland. Keep an eye out with them amongst your visiting Chaffinches – they look quite similar and have similar feeding habitats, and they’ll likely only hang around for a couple of weeks, returning to Scandinavia and northern Europe in the latter stages of the winter.

Brambling – Amber List (4% of Irish Gardens)

Brambling is a species of finch that doesn’t breed here and only occurs here in very small numbers each winter, and their listing is therefore due to declines at European level rather than anything here in Ireland. Keep an eye out with them amongst your visiting Chaffinches – they look quite similar and have similar feeding habitats, and they’ll likely only hang around for a couple of weeks, returning to Scandinavia and northern Europe in the latter stages of the winter.

Meadow Pipit – Red list (3% of Irish Gardens)

Meadow Pipit too are red listed due to significant declines at global level due to agricultural intensification. Their numbers have relatively stable in Ireland over the last twenty years, however. Though not a common garden species, we get a large spike in reports of Meadow Pipits when cold and frosty weather forces them to seek unfrozen ground for foraging. They’re a species whose numbers tend to decline rapidly after a cold winter, taking a couple of years to bounce back.

Meadow Pipit – Red list (3% of Irish Gardens)

Meadow Pipit too are red listed due to significant declines at global level due to agricultural intensification. Their numbers have relatively stable in Ireland over the last twenty years, however. Though not a common garden species, we get a large spike in reports of Meadow Pipits when cold and frosty weather forces them to seek unfrozen ground for foraging. They’re a species whose numbers tend to decline rapidly after a cold winter, taking a couple of years to bounce back.

For more information about the 'Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland' list, click here.

We are hugely grateful to Ballymaloe for their sponsorship and support of the Irish Garden Bird Survey.

For more details about the Irish Garden Bird Survey click here, or download the survey form below.