Little Tern

| Irish Name: | Geabhróg bheag |

| Scientific name: | Sterna albifrons |

| Bird Family: | Terns |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

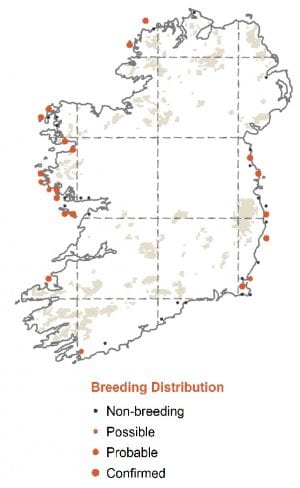

Rare summer visitor from April to late August to shingle or sandy beaches, mainly on the east and west coasts.

Identification

The smallest of the terns breeding in Ireland. Small slender seabird with narrow, pointed wings, long forked tail and long, pointed bill. Grey above and white below, dark cap to head, white forehead in all plumages. Flight is light and buoyant, hovers rapidly while foraging over the sea before repeatedly diving in. Has a dark leading edge to the primaries of its long narrow wings. Adult summer bird has long yellow bill with black tip. In winter plumage the white of the forehead extends up over the fore crown, the legs darken and the bill is all black. Juvenile plumage is distinct from the adult with dark bill, barred mantle and dark upper forewing.

Voice

Sharp, rasping and repeated.

Diet

Chiefly marine fish.

Breeding

Nest colonially on the ground on shingle beaches, making them very vulnerable to poor weather and ground predators. Only a few colonies are found in Ireland, with the majority breeding in Counties Louth, Wicklow and Wexford.

Wintering

Winters in coastal areas in western Africa.

Monitored by

BirdWatch Ireland has been monitoring and protecting breeding Little Terns at Kilcoole beach (Co. Wicklow) since 1985. In addition, the BirdWatch Ireland Fingal Branch have a Little Tern conservation project at Portrane (Co. Dublin), and BirdWatch Ireland partner with Louth Nature Trust to protect the Baltray (Co. Louth) colony.

Blog posts about this bird

A successful year for east coast Little Terns in 2024

Thankfully, 2024 proved to be a very successful year for Little Terns on the east coast of Ireland, with increased nesting numbers across all of the colonies managed by BirdWatch Ireland, the National Parks and Wildlife Service, BirdWatch Ireland Fingal Branch and Louth Nature Trust. While everything didn’t always go according to plan, the number of chicks fledged overall was pretty good too.

Kilcoole (Wicklow)

The conservation of Little Terns at Kilcoole is a National Parks and Wildlife Service project, run by BirdWatch Ireland in 2024, and we work closely with NPWS staff in Wicklow throughout the season to give the birds the best possible chance of success. Our wardens were in for a surprise this year when the first Little Tern eggs arrived on May 9th, almost a week earlier than usual and right in the middle of the already busy set-up period! While it didn’t put a stop to the work, it was necessary to proceed with caution to ensure that the fence installation did not disturb nesting birds. Thankfully, everything went smoothly and chicks from all of those early nests hatched successfully. At its peak in early June, we recorded over 285 nesting pairs of Little Terns at Kilcoole. This is the highest-ever number for the project and a long way from the 14 pairs recorded at the project’s onset many years ago. Kilcoole is by far the biggest colony of Little Terns in Ireland, and one of the biggest in all of Ireland and the UK, a testament to many years of conservation efforts by the National Parks and Wildlife Service and BirdWatch Ireland. We also know from our ringing studies that Kilcoole-born birds have moved to other Irish colonies to nest, helping those colonies grow. In early June, the combination of Hooded Crow predation, stormy weather and a high tide led to the loss of many chicks. “If these impacts happened earlier in the season when most were still on their eggs, there would have been the time and opportunity for birds to relay. Unfortunately, because of the timing in mid-June, many of the birds were too late to try again,” said Manager of the Kilcoole Little Tern Project, Brian Burke.Little Tern ringing at Kilcoole. Photo: Oonagh Duggan. Photo taken under NPWS licence.

It was a low point of the season for everyone involved, though an unfortunate reality when it comes to conservation work. Despite our best efforts to control predators in the vicinity of the colony, these two Hooded Crows caused a lot of damage before they could be stopped. There is unfortunately little that can be done when strong winds and high tides combine to bring the water up the beach and we have been lucky to avoid any significant washouts in recent years. Thankfully, the rest of the season went smoothly and the number of chicks that ultimately fledged was similar to previous years. “The Kilcoole Little Tern conservation project is a fantastic example of what can be achieved with long-term funding and continued efforts to address conservation problems and develop expertise over time. Kilcoole wasn’t an immediate success, but over time we’ve worked closely with NPWS to address the issues the birds face and to get to the stage where we have more good years than bad years,” said Brian. You can read more about the Kilcoole Little Tern Project here. The Kilcoole Little Tern Project is an NPWS project run by BirdWatch Ireland under a competitive tender agreement in 2024.Portrane (Dublin)

The BirdWatch Ireland Fingal Branch has been running the voluntary Portrane Little Tern project since 2018. Between 20 and 30 volunteers are involved in the project in a given year, with Tom Kavanagh and Paul Lynch at the helm. The group, who describe themselves as “a service provider for the avian species that choose to spend their summer at Portrane” spent over 2000 hours wardening at the colony this year. Like the Kilcoole colony, the Little Terns arrived in Portrane early this season. On May 6th, at least 20 adults were recorded at the site, with the first Little Tern egg found on May 14th. This early start proved advantageous for the Little Terns as it meant that they were ahead of many of their regular predators. Kestrel, Sparrowhawk and other predators had no chicks of their own to feed for most of the Little Tern season and so their visits to the site were infrequent. 2024 turned out to be the most successful year to date for Portrane, with a total of 78 eggs laid, 53 confirmed chicks fledged plus another seven unconfirmed. Over 120 chicks have fledged since the project started in 2018. “We are feeling brilliant about this year’s success. We find it more and more heartening and motivating with each year. You never know if a tragedy of some type will happen, whether it is a high tide or predation by a fox, but thankfully, we had no tragedies this year,” said Paul. In an effort to protect Little Tern nests that are at risk from high tides, the Portrane team use flower pots to raise them. This simple action, which is carried out under NPWS licence, has proved very successful to date. The Portrane Little Tern project continues to go from strength to strength. In addition to recording a record number of fledged chicks in 2024, the initiative has also garnered a huge amount of public support since it was established. The dedicated team of volunteers grow in numbers and expertise each year.Little Terns in Portrane. Photos: Paul Lynch. All photos taken under NPWS licence.

Paul’s awareness of the vulnerability of the Little Tern nests has been, and remains, the driving force behind his work at the colony. He and the team hope to encourage others to get on board next season, saying that once people get involved, they are hooked. “It would be great to have more people on board next year so if anyone is interested in getting involved, please get in touch. Anyone can play a role. We say if you can clap your hands and scare away crows, there is a job for you!” he added. You can read more about the Little Tern work in Portrane here and access the 2024 report here. The Little Tern Conservation Project in Portrane is managed by Birdwatch Ireland’s Fingal branch. In 2024, this project received support from The Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage through the National Parks and Wildlife Service’s National Biodiversity Action Plan Fund, and by Fingal County Council.Cahore (Wexford)

The Cahore Little Tern Project in Co. Wexford is run by the National Parks and Wildlife Service, in close collaboration with volunteers from Ballygarrett Tidy Towns. In 2024, NPWS were able to scale up the project to protect nesting Little Tern and Ringed Plover on the beach and increase local awareness of the birds and this very special colony. BirdWatch Ireland were very happy to assist with ringing tern chicks at Cahore this year, helping to improve our collective efforts to monitor and learn more about the population dynamics of Little Terns in Ireland. The Cahore project has been a great success to date, with the number of Little Tern nests increasing from 22 in 2023 to approximately 62 in 2024, with 82 egg clutches. While the site was hit with bad weather in June, at a critical time with many nests lost, thankfully, many pairs reared second clutches. You can learn more about the Cahore Little Tern Project here.Baltray

The Little Tern project at Baltray, Co. Louth commenced in 2007. It was initially run by a team of volunteers, whose efforts later resulted in the foundation of the Louth Nature Trust. The Trust has run the Project at Baltray ever since. The Baltray Little Terns arrived later than those at Kilcoole and Portrane this year, with the first nest discovered on May 20th. This season, a total of 253 eggs were counted onsite from 112 nesting attempts. 201 hatchlings were produced, and 167 successfully fledged. You can read more about the Little Tern work in Baltray here and access the 2024 report here. The Little Tern Conservation Project in Baltray, Co. Louth is managed by Louth Nature Trust. In 2024 this project was funded by Louth County Council Biodiversity Dept, NPWS, Dept of Housing Local Government and Heritage, Dublin Zoo.

Devastating Bird Flu impacts on Irish seabirds revealed in new study

A new study has revealed the devastating toll of the 2023 bird flu outbreak on Ireland’s tern species at their most important colonies, with Common Terns in particular suffering huge losses.

The recent highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 outbreak was the worst ever seen in Ireland, the UK and Europe. Details of the 2023 outbreak in Ireland, the number of birds that died at key breeding colonies, and the effect it has had on nesting numbers in 2024, have been published in the journal Bird Study by staff of BirdWatch Ireland and the National Parks and Wildlife Service. It focuses on colonies in Dublin (Rockabill Island, Dublin Port, Dalkey Island) and Wexford (Lady’s Island Lake) which have been subject to successful conservation efforts for decades, and the bird flu outbreak has come as a huge setback.

The full study entitled "A case study of the 2023 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak in tern (Sternidae) colonies on the east coast of the Republic of Ireland" was published in the journal Bird Study and can be accessed here.

A BirdWatch Ireland Tern Warden removes dead birds during the 2023 avian flu outbreak.

Common Terns suffered very high mortality across all colonies in 2023, with over 700 adult birds and over 1,100 chicks found dead by wardens in colonies at Rockabill, Dublin Port and Lady’s Island Lake. Many more will have died at sea and elsewhere along the coast and not been found, and a census of nests this year recorded a devastating loss of 1,250 breeding pairs across the colonies. In the case of Dublin Port, the colony was halved in a single year, representing the lowest number of nests in 19 years, and similarly the lowest on Rockabill Island since 2003. “The experience of visiting the colony during the outbreak and seeing so many dead and dying birds was really difficult,” said Helen Boland, manager of the Dublin Bay Birds Project. "We’re used to visiting the colony when it’s full of life, so to see so many lost in such a short space of time really had us worried about the future of the species. Terns are long-lived birds that only lay a small number of eggs per year, so losing adult birds is much more damaging to the population than having a bad breeding season.”Arctic Tern. Photo: Kevin Murphy

Arctic Terns were down by 160 breeding pairs, a 20% decline, across the colonies this year due to avian flu. The small colony at Dalkey Island suffered complete breeding failure early in summer 2023 due to rat predation, and this appears to have saved them from contracting avian flu as the birds had deserted before the virus reached Ireland. Arctic Terns lead a very challenging life, not just when trying to find safe places to nest on the Irish coast, but they migrate to Antarctica in the winter – a round trip of nearly 100,000km per year. They have been struggling to nest successfully at some key colonies in recent years, largely due to predation. This, coupled with the fact that Arctic Terns lay fewer eggs than Common Terns, means their recovery is expected to be much slower. Ireland holds 95% of the entire European population of the rare Roseate Tern, concentrated at Rockabill island in Dublin and Lady’s Island Lake in Wexford. Having so many birds at only two sites makes them particularly vulnerable to problems like disease, and their only colony in Britain had already been hit by bird flu in both 2022 and 2023. Despite 65 adult birds and 135 chicks being found dead in Irish colonies during the 2023 outbreak, this didn’t translate into significant losses this year; Lady’s Island was down by 31 pairs, but Rockabill managed to increase by 75 pairs. “The Roseate Tern numbers this year were a pleasant surprise and higher than we expected considering the losses we know came from avian flu,” said Dr. Steve Newton, BirdWatch Ireland’s Senior Seabird Conservationist. “It seems that the high number of chicks fledged in recent years means that recruitment of young birds into the colony was higher than the number of birds lost to bird flu. We’re still expecting to see slow or stalled population growth in the next few years, but it could have been much worse for the Roseates." The Sandwich Tern is Ireland’s largest species of tern, and over 1,500 pairs nest in Wexford. Sandwich Tern colonies all over the UK and Europe were hit with avian flu in 2022, but the virus didn’t reach Irish colonies that year. Nesting numbers last year indicate that Irish Sandwich Terns had suffered mortality on migration and in the wintering grounds however, with a loss of 300 pairs. It is assumed the remaining birds had developed some level of immunity to the virus and therefore escaped summer 2023 relatively unscathed, and actually bounced back to pre-flu numbers this year. This provides some encouragement that the birds can bounce back quickly, though it may simply be that the increase in birds is a result of immigration from other colonies.

Roseate Terns: Photo: Brian Burke.

Conservation staff of BirdWatch Ireland and NPWS began summer 2024 with a sense of trepidation that bird flu might return, but thankfully there were no signs of it in any of the colonies and most managed to have a successful breeding season this year. With only half the number of nesting pairs it had in 2023, the Dublin Port Tern colony had its most successful breeding season ever, with most pairs managing to fledge two chicks. Elsewhere, Roseate Terns at Rockabill did well, fledging at least one chick on average per pair. The Common Terns at Rockabill, and all tern species at Lady’s Island fared ok but generally faced problems with predation by gulls and foxes, amongst other species, and their greatly reduced numbers may have left them more vulnerable to predation. The long-term tern conservation work by BirdWatch Ireland and the National Parks and Wildlife Service, and long-term support from Dublin Port Company, mean we are well-placed to facilitate recovery at the east coast tern colonies, but avian flu likely impacted west-coast and inland tern sites too. The colonies discussed here are the most important ones nationally for these four tern species and the impact of avian flu emphasizes the importance of not having ‘all of our eggs in one basket’. BirdWatch Ireland’s new Strategy outlines our intention to expand our work to inland and west-coast tern colonies and help secure the status of these species all over the country. Despite calls from BirdWatch Ireland, the Republic of Ireland has yet to develop a formalised plan for the monitoring and management of HPAI in wild birds. The role of various state agencies in such an outbreak is not clear, with some seemingly prioritizing impacts on livestock, others on potential public health implications, but little in the way of monitoring and managing the impact on wild birds. In the absence of comprehensive guidelines, regular meetings between BirdWatch Ireland and the NPWS proved invaluable in 2023. These meetings facilitated a comprehensive and adaptive approach as new guidance emerged from authorities in the UK and Europe and as the HPAI situation developed. It also allowed for a range of precautions to be implemented to minimise the risk of spreading the virus within or between colonies, or to people, while maintaining conservation efforts and long-term monitoring. This paper makes several key recommendations for future HPAI management and procedures in Ireland. It calls for the establishment of a more direct relationship between DAFM, NPWS and BirdWatch Ireland to allow for a more strategic response to outbreaks; the clarification of roles and responsibilities across all relevant government bodies; better resourcing to manage outbreaks and an increase in annual monitoring at Irish seabird colonies wherever possible to help ensure that threats such as HPAI can be monitored in real-time. It is vital that changes are enacted without delay, not only to prevent future seabird losses in the 2025 breeding season, but also to protect the many waterbird species that winter in Ireland and are too at serious risk from HPAI. Despite two cases of avian flu in Little Terns in Ireland, the species escaped largely unscathed and almost all colonies reported increased nesting numbers in 2024. We will report on the Little Tern breeding season in the coming weeks.The full study entitled "A case study of the 2023 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak in tern (Sternidae) colonies on the east coast of the Republic of Ireland" was published in the journal Bird Study and can be accessed here.

The Rockabill Tern conservation project is a joint project between the National Parks & Wildlife Service and BirdWatch Ireland. https://www.npws.ie/

The Dublin Port Tern Conservation project is funded by Dublin Port Company as part of BirdWatch Ireland's 'Dublin Bay Birds Project'. https://www.dublinport.ie/

The Tern conservation project at Lady's Island Lake is a National Parks & Wildlife Service project, delivered by BirdWatch Ireland after a competitive tender process. https://www.npws.ie/