Mediterranean Gull

| Irish Name: | Sléibhín meánmhuirí |

| Scientific name: | Larus melanocephalus |

| Bird Family: | Gulls |

amber

Conservation status

Conservation status

Status

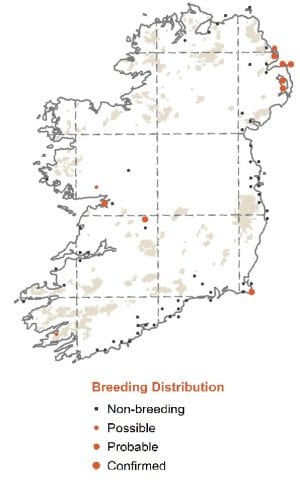

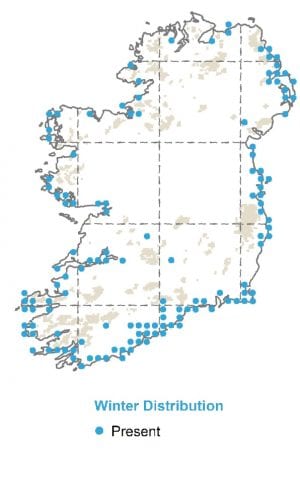

Breeds in small numbers in the south-east. Winter visitor from northwest France, Belgium and the Netherlands, occurring from September to April.

Identification

A small gull, adults are very pale grey above with white underparts and unmistakable all white outer wing feathers. Adults have a black hood and bright red legs and bill in the breeding season, In the winter, the hood is replaced by a dark markings on the head and the bill and legs are less bright. Similar to Black-headed Gull, but slightly bigger with shorter, less pointed wings, a shorter, thicker bill and longer legs. Mediterranean Gulls have three age groups and attain adult plumage after two years when they moult into adult winter plumage. Juveniles have dark, strongly marked upperparts, tail band and dark legs. First year birds retain the dark heavily marked upperwings and tail band, but have a very pale mantle as adults birds do. Second year birds more closely resemble adult birds but show some dark markings in the outer wing feathers.

Voice

A characteristic "mewing", noticeably different in comparison to Black-headed Gull. Mediterranean Gull tends to be less vocal than other gull species in winter.

Diet

Terrestrial and aquatic insects, marine molluscs and fish.

Breeding

A recent colonist, the Mediterranean Gull arrived in Ireland in 1995 and first bred in the Republic in 1996 in Co. Wexford. Prefers low lying islands near the coast on which to breed. Only two or three pairs breed but this is likely to increase with more and more birds seen in suitable habitat in the breeding season. Regularly breeds, at Our Lady's Island Lake in Co. Wexford, along with other nesting seabirds, including Black-headed Gulls, with which it is often associated. The bulk of the population of this species breeds in Eastern Europe, with small colonies in western regions.

Wintering

Present in Ireland as a wintering species in increasing numbers. Is widespread around the east coast and can also been seen elsewhere in smaller numbers. Sandycove in south Co. Dublin is particularly good for this species during the winter months.

Monitored by

Blog posts about this bird

New protected area off Wexford coast is a step forward for vulnerable seabirds

The recent announcement of the new “Seas off Wexford” Special Protection Area (SPA) is certainly news to be welcomed.

For such a designation to be as effective as it can be, it is crucial that strong and effective conservation objectives and management plans are ambitious and that stakeholders are consulted throughout the process. It would be most welcome if the designation of new marine SPAs also led to a new vision for management of Ireland’s entire network of SPAs. BirdWatch Ireland calls on government to ensure that management plans are put in place for SPAs on both land and sea and that a whole-of-government approach is taken to implement them properly to safeguard the future of the birds they are intended to protect.

Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage Darragh O’Brien recently designated the new SPA of marine waters off the coast of Wexford which, at over 305,000 hectares, is the largest SPA designated in the history of the state. These waters provide extremely important food sources for seabirds, including Red-listed species such as Puffin, Kittiwake, Common Scoter and many other vulnerable Amber-listed species such as Fulmar, Manx Shearwater, Shag, Cormorant, Black-headed Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull, Herring Gull, Roseate Tern, Red-throated Diver, Gannet, Common Tern, Little Tern, Sandwich Tern, Mediterranean Gull and Guillemot.

Kittiwake. Photo: Colum Clarke.

Under EU legislation, the Irish government has made a commitment to designate 10% of its waters as protected by 2025, and a total of 30% by 2030. This new designation increases the percentage of Ireland’s marine protected waters to 9.4%, just under the 2025 target. While this is certainly a step in the right direction, many questions remain, primarily, what will “protection” look like in practice? It is paramount that this is made clear in the soon-to-be-published SPA’s conservation objectives, which should detail the activities that will and will not be permitted in the SPA, among other measures. We look forward to reading them shortly. At the same time, BirdWatch Ireland in collaboration with BirdLife Europe and BirdLife International are mapping Ireland’s marine Important Bird Areas according to international and standardised BirdLife International criteria under a project funded by the Flotilla Foundation. This is an important time for our seabirds and it is welcome to see the government’s focus finally on setting out protected areas for them.

Red-throated Diver. Photo: Chris Gomersall

While the finer details about the Wexford SPA have yet to come to light, it is clear that certain activities will not be permitted in the Wexford SPA. The Minister has issued a Direction in relation to certain activities, which must not be carried out within or close to the SPA, unless consent is lawfully given. The listed activities are reclamation including infilling; blasting, drilling, dredging or otherwise disturbing or removing fossils, rock, minerals, mud, sand, gravel or other sediment; introduction or reintroduction of plants or animals not found in the area; scientific research which involves the removal of biological material; any activity intended to disturb birds; undertaking acoustic surveys in the marine environment and developing or consenting to the development or operation of commercial recreational/ visitor facilities or organised recreational activities.

Little Terns.

Together with our partners at Fair Seas – a coalition of Ireland’s leading environmental NGOs and environmental networks of which BirdWatch Ireland is a founding member – we have been calling for the government to meet their targets, but this alone is not enough. More action must be taken in order for us to adequately protect these important marine habitats and the many species that they support. Any move to better protect important habitats for birds is to be welcomed, and this is certainly no different. We are urging the Irish government to be ambitious in their plans for this new SPA and stress the need for focused community engagement in the surrounding areas. We also continue our urgent calls for the publication of the long-awaited Marine Protected Areas (MPA) Bill.